Amaze project aims to take 3D printing 'into metal age'

- Published

This concept Mars probe features 3D printed components

The European Space Agency has unveiled plans to "take 3D printing into the metal age" by building parts for jets, spacecraft and fusion projects.

The Amaze project, external brings together 28 institutions to develop new metal components which are lighter, stronger and cheaper than conventional parts.

Additive manufacturing (or "3D printing") has already revolutionised the design of plastic products.

Printing metal parts for rockets and planes would cut waste and save money.

The layered method of assembly also allows intricate designs - geometries which are impossible to achieve with conventional metal casting.

Parts for cars and satellites can be optimised to be lighter and - simultaneously - incredibly robust.

Tungsten alloy components that can withstand temperatures of 3,000C were unveiled at Amaze's launch on Tuesday at London's Science Museum, external.

At such extreme temperatures they can survive inside nuclear fusion reactors and on the nozzles of rockets.

"We want to build the best quality metal products ever made. Objects you can't possibly manufacture any other way," said David Jarvis, Esa's head of new materials and energy research.

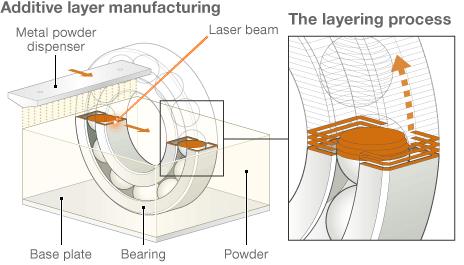

Computer-aided design software determines shape of 3D model using cross-sections

Laser etches the shape of cross-section into metal powder and heats it so it solidifies and creates a solid layer

More powder is spread to create the next layer and so on until the 3D object is created

By leaving one non-solid layer in between, interlocking structures can be created

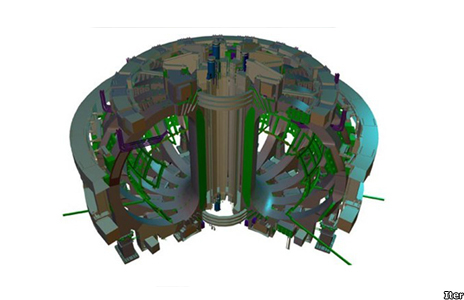

"To build a [fusion reactor], like Iter, external, you somehow have to take the heat of the Sun and put it in a metal box.

"3,000C is as hot as you can imagine for engineering.

"If we can get 3D metal printing to work, we are well on the way to commercial nuclear fusion."

Additive manufacturing with metal is not new; General Electric, for example, has used the technique, external to make fuel injectors for one of its aircraft engines. China claims to be using 3D printing to manufacture load-bearing components in aircraft.

And in July, Nasa announced that it had successfully tested a 3D-printed rocket engine part.

Amaze is a loose acronym for Additive Manufacturing Aiming Towards Zero Waste and Efficient Production of High-Tech Metal Products.

The 20m-euro project brings together 28 partners from European industry and academia - including Airbus, Astrium, Norsk Titanium, Cranfield University, EADS, and the Culham Centre for Fusion Energy.

Factory sites are being set up in France, Germany, Italy, Norway and the UK to develop the industrial supply chain.

Hinges for the Airbus A320 - conventional (background) and 3D printed (foreground)

Amaze researchers have already begun printing metal jet engine parts and aeroplane wing sections up to 2m in size.

These high-strength components are typically built from expensive, exotic metals such as titanium, tantalum and vanadium.

Using traditional techniques to fashion metal objects often wastes precious raw material.

Whereas additive manufacturing - building parts up layer-on-layer from 3D digital data - has the potential to produce almost "zero waste".

"To produce one kilo of metal, you use one kilo of metal - not 20 kilos," says Esa's Franco Ongaro.

"We need to clean up our act - the space industry needs to be more green. And this technique will help us."

Printing objects as a single piece - without welding or bolting - can make them both stronger and lighter.

A weight reduction of even 1kg for a long-range aircraft will save hundreds of thousands of dollars over its lifespan.

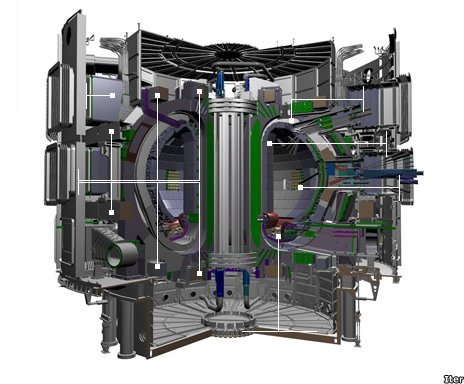

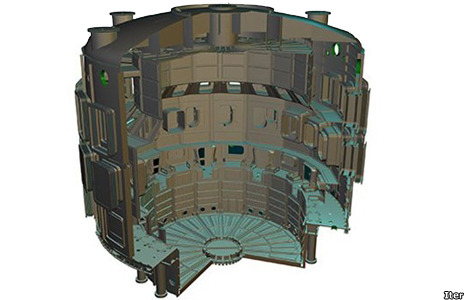

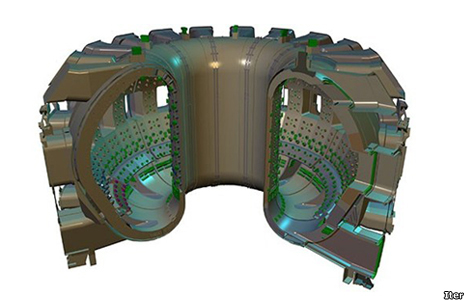

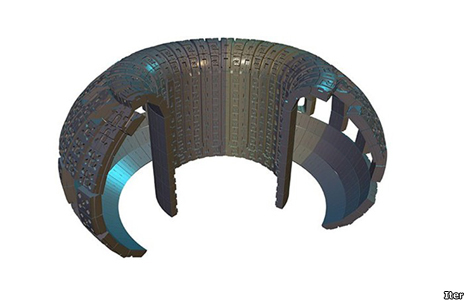

Cryostat

The cryostat holds the vacuum vessel and acts as a giant fridge maintaining the low temperature needed for the superconducting magnets.

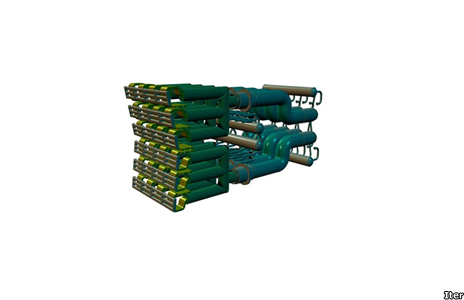

Magnets

The magnet system confines and controls the plasma inside the vacuum vessel and will generate a magnetic field 200,000 times higher than the Earth.

Vacuum

The vacuum vessel is a doughnut-shaped chamber in which the fusion reaction takes place as the plasma particles spiral continuously without touching the walls.

Blanket

The blanket covers the interior surfaces of the vacuum vessel, shielding the vessel and superconducting magnets from the heat and high-energy neutrons produced by the fusion reaction.

Divertor

The divertor sits at the bottom of the vacuum vessel and acts like an exhaust system, extracting heat and helium ash and other impurities from the plasma.

Heaters

For the gas in the vacuum chamber to become plasma, the temperatures inside the reactor need to reach 150 million degrees celsius—or ten times the temperature of the centre of the Sun.

"Our ultimate aim is to print a satellite in a single piece. One chunk of metal, that doesn't need to be welded or bolted," said Jarvis.

"To do that would save 50% of the costs - millions of euros."

But Jarvis is candid about the problems and inefficiencies that still need to be overcome - what he calls the "dirty secrets" of 3D printing.

"One common problem is porosity - small air bubbles in the product. Rough surface finishing is an issue too," he said.

"We need to understand these defects and eliminate them - if we want to achieve industrial quality.

"And we need to make the process repeatable - scale it up.

"We can't do all this unless we collaborate between industries - space, fusion, aeronautics.

"We need all these teams working together and sharing."

- Published10 October 2013

- Published30 September 2013

- Published15 July 2013

- Published18 August 2013

- Published9 May 2013