Kercher trial: How does DNA contamination occur?

- Published

Potential for the contamination of forensic DNA evidence has been highlighted by the Meredith Kercher murder trial. But just how much of a problem is it and what lessons should be drawn?

The high-profile retrial of Amanda Knox and Raffaele Sollecito, who had been imprisoned for the killing of Meredith Kercher, has placed renewed scrutiny on the DNA analysis carried out in the case.

An Italian court has now reinstated the 2009 guilty verdicts which were overturned on appeal in 2011, handing down a sentence of 28 years and six months for Knox and 25 years for Sollecito.

During the retrial, the judge ordered a new DNA test on the knife that prosecutors had submitted as evidence.

But some independent forensic scientists told the BBC this knife (which had been considered a possible murder weapon) should never have been given the importance it was because there was no evidence of blood found on it.

Greg Hampikian, from Boise State University in Idaho, US, is one of them. The forensic expert is critical of the way DNA evidence was handled.

"I could see the problem with the case right away," says Dr Hampikian, who adds that he became interested in the case early on.

A knife recovered from Sollecito's house was found to have Ms Knox's DNA on the handle and a small amount of DNA on the blade "consistent with the victim".

Dr Hampikian, who founded the Idaho Innocence Project at Boise State University, an organisation that investigates claims of wrongful conviction, says: "That is significant because Miss Kercher had never gone to that house, so what is she doing on the blade of the knife?

"While that may seem on its face to be evidence of a crime, in order to substantiate such a small amount of DNA you look for blood, and I can't emphasise enough how small this was - it was just a few cells."

But there was no evidence of blood or any other body fluids found, the Boise State researcher points out.

"You can't really wash the blood off and leave the DNA in any practical sense. That means that the few cells or molecules might have been from the laboratory after they amplified Miss Kercher's DNA," he explains.

By amplification, Dr Hampikian is referring to the common process by which millions of copies are made from isolated DNA strands, using a method called "polymerase chain reaction", or PCR.

This concern was not his alone. There have been claims that the initial evidence was handled using dirty gloves and that investigators entered the crime scene without protective clothing.

The defence team also said that the amount of DNA was too small to be accurately attributable to Miss Knox and that it could have been contaminated. This claim was rejected by the prosecutors who said that they used world-class technology and had highly experienced officers.

From the initial collection of items at the scene of the murder, significant traces of just two people's DNA were found - that of the victim and one other person, Rudy Guede. His bloody fingerprint was discovered on the wall of Ms Kercher's bedroom.

Some 46 days after the crime, a bra clasp was found which contained some of Sollecito's DNA.

Meredith Kercher was found with her throat cut at this property in her Perugia flat

"The clasp was handed back and forth. It's the only thing that has DNA consistent with Raffaele and a number of other people, so I think that's probably contamination as well," adds Dr Hampikian.

To highlight how easily contamination in DNA evidence can occur, Dr Hampikian's team carried out a demonstration.

They picked up used drink cans wearing clean gloves and then placed a new knife into an evidence bag without changing gloves. The knife was subsequently found to have tiny fragments of traceable DNA which had been transferred from the can.

A widely cited example of contamination comes from the case of the "Phantom of Heillbronn", external, once believed to be Germany's most dangerous woman.

She had been connected to six murders based on DNA apparently found at the scene. In fact, the swabs used to collect evidence had been contaminated by an innocent factory worker.

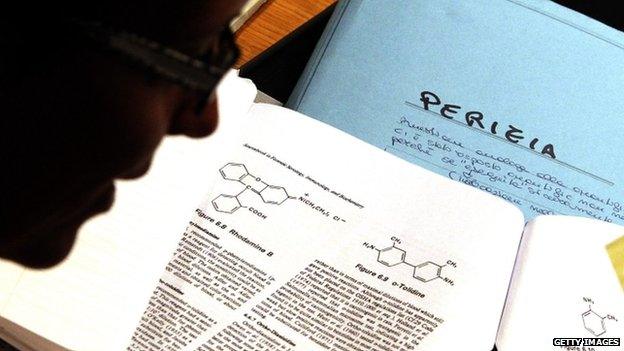

An independent review questioned the quality of the DNA evidence used to secure the convictions of Knox and Sollecito

The hunt for the phantom spanned a period of 15 years. Technological advances now mean that DNA profiles can be generated from tiny amounts of genetic material.

So sensitive are the analysis methods that traces of DNA can be found on clothes even after they have been through a washing cycle.

For this reason, says David Balding from University College London's Genetics Institute, the word "contamination" should be used with care, because DNA is everywhere in our environment.

DNA found on the knife could have been the result of contamination, some experts suggest

He is another forensic scientist who reviewed evidence from the Kercher case.

"Every crime sample that was ever collected was contaminated. Even in the most pristine conditions in a laboratory, you cannot have a DNA-free environment," he says.

"The point is you have to allow for that to do a correct evaluation of the evidence; all of that kind of contamination just isn't a problem, as it's not going to match. The only contamination that matters is something that would have got the suspect's DNA."

Prof Balding helped to analyse the bra clasp on which Raffaele Sollecito's DNA was detected in the Kercher investigation.

"A lot of people walked in and out of the room, there's been a lot of controversy about that. But could any of that have brought Sollecito's DNA into the room? There's no doubt that his DNA is on the bra clasp; the only question is how it got there."

Another point of contention was the discovery that a third, unknown person's DNA profile retrieved from the bra clasp was overlooked by investigators. The appeal court subsequently ruled that the evidence could no longer be relied upon.

The precise mechanics of the process by which a person's DNA can be transferred from one object to another, without that person being present, is still poorly understood.

Allan Jamieson, director of the Forensic Institute in Glasgow, is keen to highlight this problem.

It is well known, he says, that DNA moves around very easily but "the reality is we don't know enough about DNA transfer to explain it".

When an object is found to have traces of several people's DNA on it, this says little about who touched the object last, Dr Jamieson explains.

"There's an unfortunate tendency for people in forensic science to want to be detectives and solve things, but that takes them beyond the science," he says.

"The science doesn't [necessarily] assist you in cases like this, because there's a known mechanism of transfer."

Jo Millington, a senior forensic scientist at Manlove Forensics, agrees. She says that "it's not really a case of who the DNA could have come from; it's more a question of how it got there".

She adds: "In the Kercher case in particular, there's not been due consideration given to how DNA can be transferred and that's rife across DNA analysis in the UK."

However, DNA analysis remains a vital frontline tool for forensic investigators.

"DNA is the best and most reliable evidence we've got, so, on the whole, we are right to put a lot of faith in it," Prof Balding explains.

"Of course, in the many millions of cases using DNA evidence there are going to be some mistakes. But there are millions of successful convictions based on DNA evidence, so that small risk is a price we have to pay."