India Mars launch stokes Asian space race with China

- Published

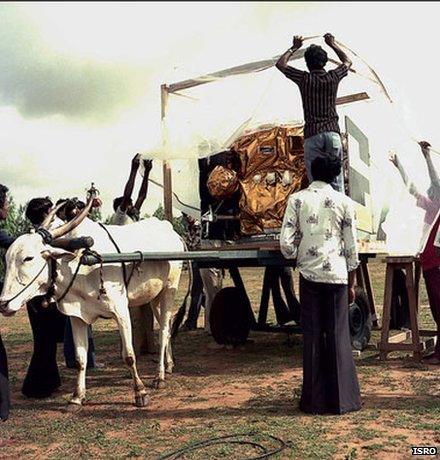

India's Mangalyaan spacecraft is built in India's state-of-the-art construction facility in Banglalore

The forthcoming launch of a spacecraft to Mars by India is likely to stoke the fires of a burgeoning Asian space race.

The Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) is making its final preparations to send an orbiter to the Red Planet.

The principal aim is to test out India's space technology to see if this emerging space-faring nation is capable of interplanetary missions.

The spacecraft will also collect scientific information about the planet's atmosphere and surface.

The Mangalyaan probe was to have been launched as early as 28 October, but rough weather in the Pacific forced officials to delay the launch by a week. The unmanned mission has a launch window lasting until 19 November.

If the mission succeeds, ISRO will become only the fourth space agency, after those in the US, Europe and Russia to have successfully sent a spacecraft to Mars.

According to Pallava Bagla, science editor of New Delhi television news and author of a book about India's space efforts, Destination Moon, the country's public are especially excited about the possibility of beating China to the Red Planet.

"If India does beat China to Mars you can imagine the national pride," he told BBC News.

The mission was announced in August last year by India's Prime Minister Manmohan Singh during his independence day speech, delivered from the ramparts of one of New Delhi's most iconic buildings - the Red Fort.

"Anything said from the ramparts of the Red Fort is always replete with national pride and national pride is written very largely and boldly on this mission," according to Mr Bagla.

In 2011, a Chinese attempt to send a spacecraft named Yinghou-1 to Mars was aborted because of a technical problem. The Indian space agency then fast-tracked its Mars mission, called Mangalyaan, readying it in just 15 months.

India has had a space programme for more than 30 years. Until recently, its priority has been to develop technologies that would directly help its poor population, such as improving its telecommunications infrastructure and environmental monitoring with satellites.

India's space programme has moved on significantly since its early days.

But in 2008, ISRO translated its formidable capability to build and launch satellites toward exploration and send a probe to the Moon, Chandrayaan-1, external. The lunar mission cost more than £55m. Now the government has spent a further £60m to go to Mars.

Poverty

Some have questioned the government's shift away from building infrastructure towards exploration, and wonder whether the money could have been better spent. It is a point that draws this robust response from Mr Bagla:

"You can't bring the 400 million people who live in poverty in India out of poverty with this £60 million," he says.

The shift towards exploration is also a hard-headed one by officials in the hope that it will have clear economic benefits, according to Prof Andrew Coates, who rejoices in the impressive title of "Head of the Solar System" at the Mullard Space Sciences Laboratory in Surrey, part of University College London.

"The exploration programme gives them something very high to aim for. If they can show the world they have what it takes to send spacecraft to other planets they can begin to sell launches and space on its launch vehicles to scientific organisations. It also brings India to the table of international space science exploration," Prof Coates explained.

Developing satellites and developing launchers is now big business. If India, or for that matter China, ease up on their investments in space exploration there is a risk that they could lose out, not least on the vital expertise that this cutting edge endeavour brings to their respective countries.

Big business

Sandeep Chachra, executive director of the poverty eradication charity Action Aid in India believes that investment in space exploration could potentially benefit the country's poorest.

China is the current high achiever in the Asian space race

"Investing in new technology, including space technology is an important part of the aspirations for an economy such as India. Developing a sophisticated technological base in a country with this level of poverty is not a simplistic contradiction " he told BBC News.

"What is important is to harness the advances that science and technology bring for the greater good and to use those advances to overcome ingrained poverty and build hope for future generations".

China though remains the greater power in space. The China National Space Administration (CNSA) has a well developed astronaut programme and an orbiting laboratory called Tiangong-1. The CNSA is planning to send its Chang'e-3 spacecraft and accompanying rover to the Moon in December.

The mission is part of an ambitious plan to send more robotic probes to the Moon with a view to eventually sending astronauts to the lunar surface.

The Japanese Space Agency (Jaxa) is also a major force in the region. It is by far the most experienced Asian space agency, with numerous unmanned scientific interplanetary missions under its belt.

"India, China and Japan are certainly eyeing each other up," says Prof Coates.

The growing rivalry is likely to see a new boom in space exploration - one that will eventually lead to more collaborative missions between the emerging space-faring nations in Asia. That might eventually lead to a truly global effort to send astronauts to Mars.

Follow Pallab on Twitter, external

- Published15 August 2012

- Published26 June 2013