Sex-starved fruit flies live shorter, more stressful lives

- Published

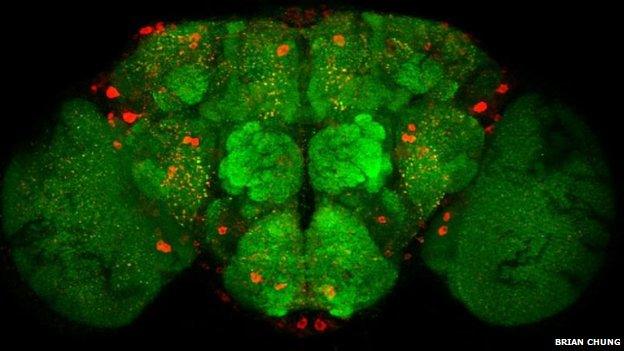

A male fruit fly - Drosophila melongaster - was genetically altered to release female pheromones

Sexual frustration impairs the health of fruit flies and causes premature death, according to new research.

Scientists found that male flies who were stimulated to mate but prevented from doing so, had their lives cut short by up to 40%.

Those allowed to copulate not only lived longer but suffered less stress.

The research is published in the Journal Science, external.

In the experiment, the flies were put in close proximity to genetically modified males who had been altered to release female sex pheromones.

These hormones are used by flies to judge whether a potential mate is nearby, so when males secreted this sexually charged scent, it instantly aroused other males.

But crucially, they were not able to mate.

The flies that were tantalised but denied any action showed more stress, a decrease in their fat-stores and had their lives cut short dramatically.

"We immediately observed that they looked quite sick very soon in the presence of these effeminised males," explained Dr Scott Pletcher at the University of Michigan, US, co-author of the research.

The common fruit fly has a very short life of about 60 days. This makes them an ideal organism to study aging as the genes that regulate a fly's lifespan have been found to closely parallel those in humans.

Male flies who expected sex had dramatically shortened lives

The team were interested in the neurons involved in aging. A brain chemical called neuropeptide F (NPF) - which has previously been linked to reward - was found to be instrumental.

When flies were exposed to an excess of female pheromones but had no opportunity to mate, their NPF levels increased.

Mating would usually regulate the neuropeptide to normal levels but when it stayed high, it caused the detrimental physiological consequences.

Costly act

The mere act of reproduction normally reduces a fly's life by about 10-15%, but the amount that their life was cut short in this study was unexpected.

"In that context mating can be quite beneficial, which is contrary to dogma. It suggests that the brain is somehow balancing this information about the environment through sensory input," Dr Pletcher told BBC News.

Neuropeptide F (red) levels increased in the brain when flies were tempted but not able to mate

"Evolutionarily we hypothesise the animals are making a bet to determine that mating will happen soon.

"Those that correctly predict may be in a better position, they either produce more sperm or devote more energy to reproduction in expectation, and this may have some consequences [if they do not mate]," Dr Pletcher added.

Female power

Timothy Weil, lecturer at the University of Cambridge zoology department who was not involved with the study, said the work suggested that less successful males could lose out in the race to pass on their genes.

"Sex and food are the biggest drivers of animal behaviour and the female fly here seems to have the power. It could be a way for females to select for the best mates as the males who are not mating as much have negative health effects," he said.

"The work suggests that acting upon these physiological changes is important for the health of the animal," Dr Weil added.

In a separate study on roundworms, also published in Science, a team found that the presence of male pheromones reduced a female's lifespan.

Dr Pletcher said this parallel finding was encouraging because worms and flies have similar pathways, "which have so far been held up in mice and likely in primates too".

- Published20 November 2013

- Published15 March 2012

- Published23 March 2012