Could Los Angeles withstand a 'megaquake'?

- Published

The Greater Los Angeles Area is home to a population of some 18 million people

As cities grow and technology evolves, the increasing level of complexity enhances vulnerability to earthquakes.

It's not a question of if the San Andreas fault ruptures in Southern California, but when.

This was the message of US Geological Survey (USGS) scientist Dr Lucy Jones here at the American Geophysical Union meeting, external in San Francisco.

Giving a public lecture at the gathering of more than 20,000 geoscientists from across the globe, Dr Jones outlined the dangers and challenges Southern California faces as it waits for the next "big one".

The region accommodates the major urban centres of Los Angeles and San Diego.

At the time of the infamous earthquake that hit San Francisco in 1906, less than one in three US citizens lived in cities, but now the overwhelming majority of the American population is urban, and urban resilience is a big issue.

Much of the current focus on earthquake planning is acted out in building regulations. Californian construction codes are based on satisfying a target of 90% probability that a building does not collapse.

In other words, there is a tacit acceptance that 10% of buildings could collapse in the vicinity of the next maximum credible earthquake. Such earthquakes hit California once every three centuries or so.

Earthquake drills are carried out to help Californians prepare for the next "big one"

In addition, in the event of such a quake, some buildings that do not collapse will nonetheless remain uninhabitable, due to the risk of collapse in aftershocks. These are given a so-called "red tag".

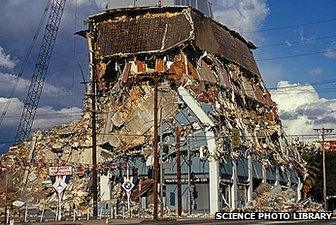

Past experience shows that this is a significant multiplier. In the magnitude 6.7 earthquake that hit Northridge, 20 miles north-west of Los Angeles in 1994, around 230 buildings collapsed but around 2,300 red tags were issued.

Similarly, in a quake that hit the San Francisco Marina District in 1989, for every collapsed building, around 10 others receive a red tag.

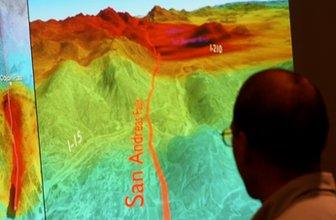

The USGS has simulated the effects of a magnitude 7.8 earthquake in Southern California

Carrying these results over to the worst-case scenarios for Los Angeles, this suggest that almost all buildings could become uninhabitable and still satisfy the definition of success for the building code.

Seismologists at the US Geological Survey have simulated the effects of the next big Californian earthquake in a programme of study called ShakeOut.

One of their computer models assumes that the next big event on the San Andreas fault will be magnitude 7.8, with a single event in which a rupture starts in Southern California near the Salton Sea and then shoots north along the fault to hit Los Angeles.

In their model, the thick sediments that downtown LA sits upon amplify the strong shaking of the quake, which would happen around 75 seconds after the first small signal of the earthquake.

Ground motions would be of "Intensity 9", corresponding to accelerations of one G, causing significant damage to buildings. The model suggests the collapse of possibly around 1% of the buildings in an area of 10 million people.

The end result would be that around half the buildings in the area would have to be abandoned. But the model's most disturbing results show that beyond the building damage there would be significant disruption of inter-dependent infrastructure.

Infrastructure, such as transportation, water supplies and communications, would be severely disrupted

Transportation, gas and electricity supplies, sewerage systems, water supplies and communications would all be affected.

Whether a modern civic society could operate under such conditions is questionable. At the instant of the USGS model earthquake, debris would close roads, extinguish traffic lights, water supplies would be cut off, and emergency responders would have difficulty operating.

Beyond that, the disruption of the supply chain also becomes an issue, pointed out Dr Jones. The move towards a "just in time" economy in grocery stores and elsewhere has introduced additional vulnerability.

The Northridge earthquake that struck in 1994 caused significant damage

There are few warehouses or stockpiles of food on the western side of the San Andreas fault.

The water system is vulnerable: 70% of the water pipes in Southern California are made of brittle concrete which would likely fail in a large quake, with LA served by water supplies that traverse the San Andreas fault.

Even repairing the pipe network was stated as an issue, since current pipe manufacture in the US is insufficient to replace the damage in under six months. Replacement by polyurethane piping, which can withstand earthquake shaking, could overcome this problem.

The impact of Hurricane Katrina in New Orleans serves as a cautionary example of the impact on society of a major natural catastrophe.

If water, power, transport and other infrastructure was cut off to downtown LA for six months or more, it seems likely that many commercial businesses would fail.

In the case of earthquakes in particular, aftershocks could cause additional psychological distress that would likely result in the net movement of populations away from the stricken zone, again damaging local economies.

First responders would have to work in challenging conditions

The largest growth decade in the history of LA was the one that followed the 1906 earthquake in San Francisco. In short, people left San Francisco and moved south.

"It will be interesting to see where LA ends up going," said Dr Jones.

"Critical infrastructure needs to be kept in place so that society can continue working."

The last big earthquake that hit California, the one at Northridge, occurred when the internet age had just got going. Now, two-thirds of the data capacity of LA is carried in fibre optic cables that cross the San Andreas fault and would likely be broken in a large quake.

Mobile phone antenna towers are not covered by earthquake building regulations. The magnitude 8.8 quake that hit Chile in 2010 wiped out all electronic communications for three days, Dr Jones said.

And there are other vulnerabilities. The ports of Long Beach and Los Angeles are the largest in the US, with 80% of container traffic and 40% of total US imports going through them.

In 1906, the fires that burned out of control in San Francisco were more destructive than the quake itself

While they themselves are not particularly vulnerable, transportation from those ports to the remainder of the US would likely be disrupted, claimed the USGS researcher, pointing out also that oil pipelines from these ports to Nevada and Arizona cross the fault, with the possibility of wildfires erupting should they be broken.

San Francisco was destroyed by fire in 1906, not by the earthquake. Fire-fighting remains a huge problem in the face of a major quake, said Dr Jones. Cascading events, where disaster moves to catastrophe, must be avoided, she continued.

Simulations suggest some 1% of buildings would collapse, but many more would become uninhabitable

The outcomes in Japan at Fukushima, where a chain of failures cascaded to a catastrophe, demonstrate the type of unforeseen consequence that may ensue following a major quake.

Should a San Andreas quake coincide with the strong Santa Ana winds that frequently blow down over LA, fires could take hold and destroy large parts of the city.

Answers to such vulnerability lie in cooperation within communities, claimed Dr Jones. And while the internet is adding a level of complexity and vulnerability to civic society, it may also impart some small hope, by allowing the development of early warning systems.

Those 75 seconds between the initial (P-wave) shake of the next big quake and the devastating impact of the secondary wave could be critical in saving life.

But Dr Jones's message rang clear: the viability of communities after a major event depends upon preparation now.