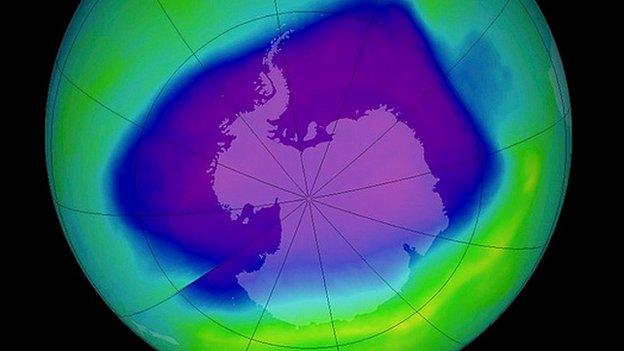

Weather 'behind ozone hole changes'

- Published

New insight has been gained into the recovery of the ozone layer.

Scientists have been puzzled why the hole, which forms each year over Antarctica, has been changing considerably in size from year to year.

Now Nasa researchers say it is the weather that is primarily driving this variability - not the ozone-destroying chemicals in the upper atmosphere.

The findings were presented at the American Geophysical Union Fall Meeting in San Francisco.

Susan Strahan, from Nasa’s Goddard Space Center in Maryland, said: “We want to measure and see that the ozone hole is being reduced.

“But to understand if the ozone hole is shrinking, we need to understand all of the different factors that cause the ozone hole area and depth to vary.”

Twenty years ago, the international Montreal Protocol came into force to phase out ozone-depleting substances such as CFCs.

These chemicals break down in the high atmosphere and release chlorine, which, in a reaction driven by the Sun, goes on to destroy ozone gas. As a result, each year, the ozone layer over the southern polar region experiences a deep thinning.

After the ban, this hole stopped getting bigger.

However, there have not yet been signs of a full recovery – and damaging ultraviolet rays from the Sun are still streaming through.

And in some years, such as 2006 and 2011, the hole appeared to be very large, while in others, such as 2012, it looked small.

Now scientists from Nasa believe that the weather plays a much more significant role in the complex system than had previously been suggested.

Dr Strahan said: “We have identified another factor that wasn’t fully recognised before: and that is how much ozone gets brought to the polar regions in the first place, by the winds.”

Satellite images show that fluctuating air temperatures and winds change the amount of ozone gas that sits above Antarctica.

And scientists believe this is dictating the apparent size of the ozone hole changes year on year.

If more ozone is brought to the lower region in the stratosphere, there is more ozone to destroy and the hole can look bigger. This was the scenario in 2006.

But in 2011, the winds brought less ozone to this lower area, so the ozone there got destroyed more quickly – again the hole looked more sizeable.

If, however, as in 2012, the winds push more ozone into the upper stratosphere, this can mask the hole below and make it look smaller.

“At the moment, it is winds and temperatures that are really controlling how big it is,” Dr Strahan added.

The team thinks meteorological conditions will continue to be the dominant driver in the process until about 2030.

After that, as the long-lasting chemicals in the atmosphere finally start to clear, the layer should start to recover.

Dr Strahan said: “We can project how quickly we think chlorine will decline in the coming decades and use this, as well as our knowledge of temperatures in Antarctica, to predict that the ozone hole will probably go away in 2070, give or take 10 years.”

Follow Rebecca on Twitter, external