Supernova 'dust factory' pictured

- Published

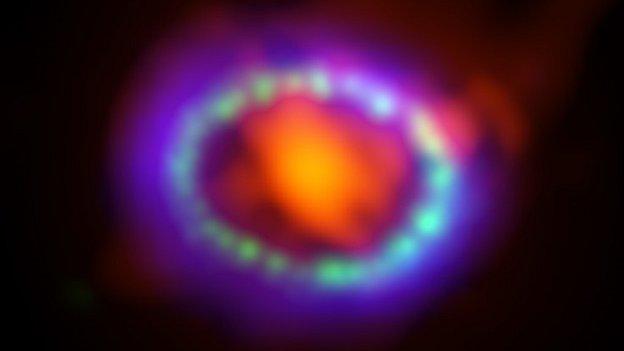

Tremendous amounts of dust (red) were detected in the centre of the supernova, within the outer shockwave (blue)

Striking images of a young supernova brimming with fresh dust have been captured by a telescope in the Chilean desert.

It is the first time astronomers have witnessed the genesis of the grains which formed galaxies in the early universe.

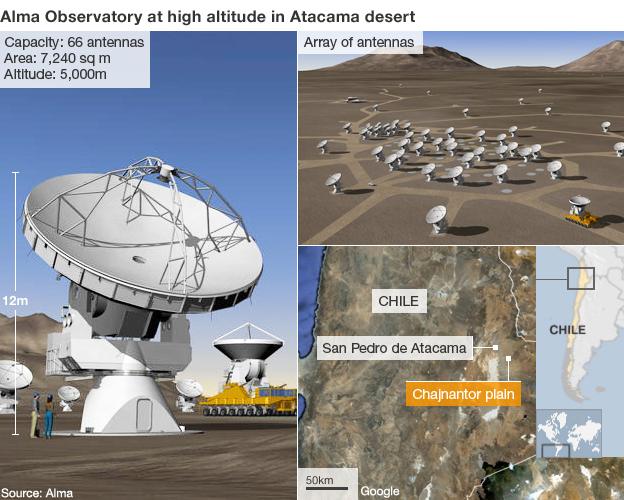

The pictures were captured by the Alma (Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array) telescope.

They were revealed at the 223rd meeting of the American Astronomical Society.

They will be published in the Astrophysical Journal Letters, external.

Fading giants

The universe is full of tiny solid particles – from the dark bands we see in the Milky Way to the beautiful clouds in iconic pictures from the Hubble telescope.

Dust collapses into planets and aids the formation of stars. But despite its ubiquity, there was no firm evidence of where it actually emerged from in the first place.

In today's universe, it largely forms around dying stars as they burn out. But these fading giants were not around at the dawn of the universe.

“It's the same problem as we have in my house – there's a lot of dust and we don't know where it comes from. Space is quite a messy place," quipped Remy Indebetouw, an astronomer with the National Radio Astronomy Observatory.

“So we took one of the most technologically advanced telescopes ever – Alma – and tried to find out how dust formed in the early universe.”

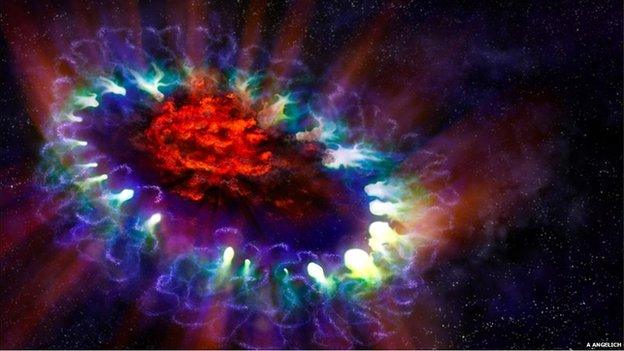

"Supernovas have long been thought to be the creators – the bright factories that burst out building blocks for galaxies. But catching one in the act is far from easy.

"And even when we do spot a supernova cloaked in a dusty plume, there's the old chicken-egg problem: how do we know that the cloud wasn't there first?”

'Not a nuisance'

To settle the argument, a team of astronomers from the UK and US used Alma to observe the glowing remains of 1987A, the closest recently observed supernova, 168,000 light-years from Earth.

They predicted that, as the gas cooled after the explosion, solid molecules would form in the centre from atoms of oxygen, carbon, and silicon bonded together.

Earlier observations of 1987A with the infrared telescope Herschel had only detected a small amount of hot dust.

But thanks to the power of the Alma radio telescope array, which stretches out over the Atacama desert, it took only 20 minutes to capture the evidence on camera.

“We found a remarkably large dust mass concentrated in the central part of the ejecta [cloud of particles],” said Dr Indebetouw.

The data from Alma was combined with observations by Nasa's Hubble and Chandra telescopes to create this supernova image

“And all of that matter – the red area you see at the centre of the picture – was there in the core of the star before it exploded.That's the exciting thing.

“People think of dust as a nuisance - something that gets in your way. But it turns out it's pretty important.”

While supernovae signal the destruction of stars, they are also the source of new material and energy, says Dr Jacco van Loon of Keele University, a co-author on the study.

“Our lives would be very different without the chemical elements that were synthesised in supernovae throughout history,” he said.

“Grains are incredibly difficult to make in the vast emptiness of space. And if supernovae indeed make lots of them, this has very important and positive consequences for the eventual formation of the Sun and the Earth.”

- Published5 January 2014

- Published18 July 2013

- Published27 November 2013