Termites inspire robot builders

- Published

The "termite" robots in action - speeded up 5 x and then 15 x real-time

US scientists have developed small robots that behave much like termites.

The insects build impressive, metres-high structures even though they can follow only simple rules and have no knowledge of an overall plan.

The Harvard researchers' robot brick-layers do something similar, sensing just the immediate area and taking limited cues from each other.

Nonetheless, as a report in Science magazine shows, the machines can also build large, coherent structures.

The researchers say this decentralised approach to robot programming can have some major advantages over very sophisticated systems.

The team gives the example of swarms of construction bots being sent into hazardous environments, such as in disaster zones or out into space.

In these types of settings, if one or more machines is destroyed, the others can continue to work together to complete the task.

Dr Justin Werfel: “Termites are the master builders of the insect world”

Contrast this with a complex robot following high-levels commands. If it fails for some reason, the whole endeavour might be doomed.

"We're not going to Mars anytime soon, but a more medium-term application might be to use similar robots in flood zones to build levees out of sandbags," said lead author Dr Justin Werfel from the Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering at Harvard University.

"That's a kind of classic of robotics: you want to use them in situations that are dirty, dangerous and dull."

Dr Werfel was summarising his research here at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS).

Environment driver

He and colleagues are addressing one type of challenge in robotics - that of finding low-level rules that can be followed by machines to give specific, predictable outcomes.

In doing so, the team is borrowing a concept from the world of social insects called "stigmergy".

This is the idea that coordinated behaviour can arise from information left in the environment.

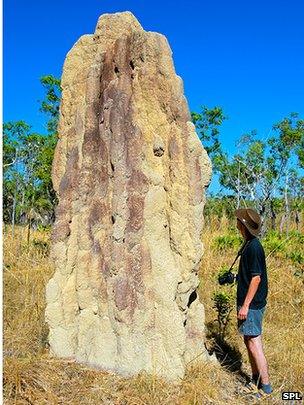

Termites are champion construction workers

When termites build their mounds, they do so by reacting to their surroundings.

An insect will pick up a lump of earth and transport it to a location. If the location is already filled, it just moves on to the next site and dumps the earth there.

Chemical trails left by the termites in front, and the very shape of the rising mound, guide the workers following behind.

The Harvard team has designed algorithms based on stigmergy for their brick-laying machines.

The scientists specify a particular structure - be that a pyramid or a castle - and the system then automatically generates the low-level rules the climbing robots must follow to guarantee the production of that structure.

Individually, the 18cm-long bots need very little information.

"They have only four simple types of sensors: infrared, ultrasound, an accelerometer for climbing, and tactile sensing - push buttons. That makes them robust and easy to program," said team-member Kirstin Petersen from the Harvard School of Engineering and Applied Sciences.

They sense the presence of bricks, other nearby bots and the grid space as they move through it.

Evolution probe

They build staircases with their bricks and walk up and down them.

But, importantly, they perceive only their immediate vicinity. They have no information on the current state of the overall structure or the actions of more distant robots.

"They have some traffic rules that tell them how to move through the work space, and these correspond to the particular type of structure being built. That is, if you ask them to build something else, the traffic rules will be different. And they also have some safety checks that ensure they never put bricks that back them into a corner, such as building a cliff they can't then climb over," explained Dr Werfel.

Bots can be removed or even added mid-task and it makes no difference. Likewise, if the structure experiences damage mid-erection, the bots merely resume construction at that point and carry the build to completion.

"You can see how this is more robust," added Dr Werfel. "If you send [the sophisticated Star Wars robot] C-3PO and it is destroyed, you're out of luck. But if you send an army of ants and half get swept away by the river, the rest can keep on working."

Commenting, Dr Judith Korb from the University of Freiburg, Germany, said it was conceivable such robots could also be used to turn the study back on living things and the mechanisms of evolution.

"It's possible you might use this program to test whether the insects do things in an optimal way. It may be that evolution has constrained them such that they follow very good solutions but not quite the best."

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external

- Published7 October 2013

- Published8 July 2013

- Published8 March 2012

- Published26 March 2011