UK storms: Risk of groundwater floods

- Published

Groundwater levels are so high in some parts of the country that flooding is likely to persist for weeks or even months, experts say.

Scientists at the British Geological Survey (BGS) say levels are likely to keep rising even if there is no more rain, as so much water is soaking through the soil.

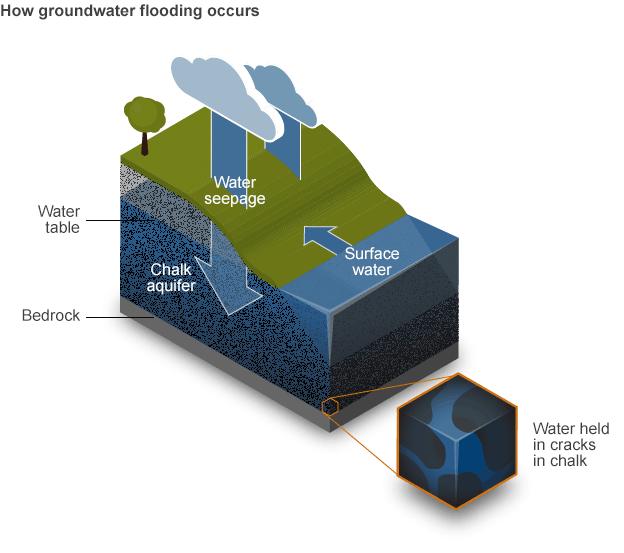

It means an increased risk of groundwater flooding, where water seeps up through the ground because the earth is so saturated it cannot hold any more water.

Last month, the Met Office said parts of England had experienced their wettest January since records began, more than 100 years ago.

New figures due out this month are also expected to confirm that the winter of 2013-14 has been the wettest on record.

Hidden threat

Engineering consultancy Jacobs estimated in 2004 that 1.6 million properties in England and Wales were at risk of groundwater flooding.

The figure, quoted by the BGS, is still regarded as broadly accurate.

What happens when you open up a borehole?

A major risk from groundwater flooding is that it does not always appear where it might be expected, rising up through cellars and floors rather than coming in through doors.

It can also cause a problem with drains and sewers where they are overwhelmed. Properties built above ground containing low-lying chalk are most vulnerable, the Environment Agency says.

Chalk is an aquifer - a type of rock in which water can flow. As the rain falls it percolates through the ground and into the cracks and pores in the chalk where it is stored.

A BGS report last month said water levels had risen by more than 30 metres in some observation wells in chalk in Hampshire.

Spring peak

Generally groundwater levels, or the levels of saturated ground, are higher in winter and reach a peak in the spring.

The changes in levels lag behind rainfall levels because the aquifers take longer to fill up and the water takes even longer to flow away underground through the narrow cracks in the rock.

During periods of prolonged high rainfall, the level of groundwater rises to the surface, causing flooding.

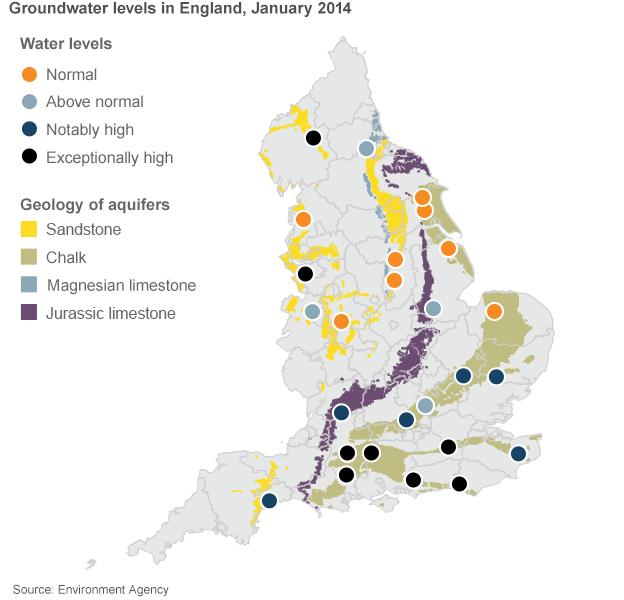

Groundwater levels in southern England, particularly in areas of chalk, are already exceptionally high after prolonged periods of heavy rain.

The BGS runs 32 boreholes across the country to measure water levels. It said nine of them showed record water levels and one had never been so full in its 179 years of operation.

"We fully expect it will take several weeks to fully return to normality," Andy McKenzie, of the BGS, told the BBC.

Precautions that can be taken against groundwater flooding are limited, partly because it is difficult to predict and also because traditional flood defences are no use.

Basements can be lined with "tanking" materials to prevent water coming in, and in some areas pumps can remove groundwater, but the effect is very localised and the problem remains of where to discharge the water.