Kepler telescope bags huge haul of planets

- Published

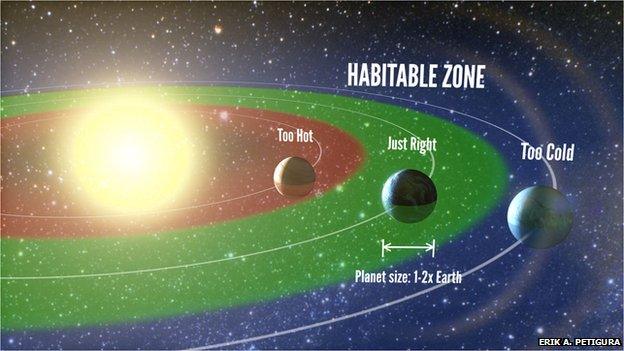

Four of the 'new' planets orbit their host suns in the "habitable zone" where water can keep a liquid state

The science team sifting data from the US space agency's (Nasa) Kepler telescope says it has identified 715 new planets beyond our Solar System.

This is a huge new haul.

In the nearly two decades since the first so-called exoplanet was discovered, researchers had claimed the detection of just over 1,000 new worlds.

Kepler's latest bounty are all in multi-planet systems; they orbit only 305 stars.

The vast majority, 95%, are smaller than our Neptune, which is four times the radius of the Earth.

Four of the new planets are less than 2.5 times the radius of Earth, and they orbit their host suns in the "habitable zone" - the region around a star where water can keep a liquid state.

Whether that is the case on these planets cannot be known for sure - Kepler's targets are hundreds of light-years in the distance, and this is too far away for very detailed investigation.

The Kepler space telescope was launched in 2009 on a $600m (£360m) mission to assess the likely population of Earth-sized planets in our Milky Way Galaxy.

Faulty pointing mechanisms eventually blunted its abilities last year, but not before it had identified thousands of possible, or "candidate", worlds in a patch of sky in the constellations Cygnus and Lyra, external.

It did this by looking for transits - the periodic dips in light that occur when planets move across the faces of stars.

Before Wednesday, the Kepler spacecraft had confirmed the existence of 246 exoplanets. It has now pushed this number up to 961. That is more than half of all the discoveries made in the field over the past 20 years.

"This is the largest windfall of planets that's ever been announced at one time," said Douglas Hudgins from Nasa's astrophysics division.

"Second, these results establish that planetary systems with multiple planets around one star, like our own Solar System, are in fact common.

"Third, we know that small planets - planets ranging from the size of Neptune down to the size of the Earth - make up the majority of planets in our galaxy."

When Kepler first started its work, the number of confirmed planets came at a trickle.

Scientists had to be sure that the variations in brightness being observed were indeed caused by transiting planets and not by a couple of stars orbiting and eclipsing each other.

The follow-up work required to make this distinction - between candidate and confirmation - was laborious.

But the sudden dump of new planets announced on Wednesday has exploited a new statistical approach referred to as "verification by multiplicity".

This rests on the recognition that if a star displays multiple dips in light, it must be planets that are responsible because it is very difficult for several stars to orbit each other in a similar way and maintain a stable configuration.

"This technique that we've introduced for wholesale planet validation will be productive in the future. These results are based on the first two years of Kepler observations and with each additional year, we'll be able to bring in a few hundred more planets," explained Jack Lissauer, a planetary scientist at Nasa's Ames Research Center.

Sara Seager is a professor of planetary science and physics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. She is not involved in the Kepler mission.

She commented: "With hundreds of new validated planets, Kepler reinforces its major finding that small planets are extremely common in our galaxy. And I'm super-excited about this, being one of the people working on the next generation of space telescopes - we hope to put up direct imaging missions, and we need to be reassured that small planets are common."

Detailed information on the latest discoveries has been posted in two, externalpapers, external on the electronic pre-print arXiv repository.

The habitable zone is the region around a star where water can keep a liquid state

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external

- Published27 February 2014

- Published20 February 2014

- Published5 November 2013

- Published22 October 2013

- Published16 August 2013