New Hebrides trench: First look at unexplored deep sea

- Published

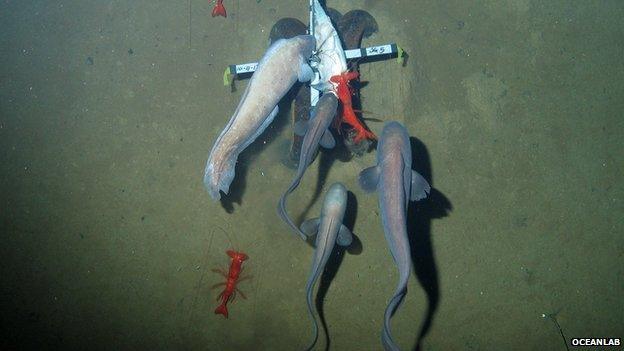

Cusk eels mingle with bright red prawns in this footage recorded in the New Hebrides trench

Scientists have had the first look at the life that thrives in one of the deepest spots in the ocean.

An expedition to the unexplored New Hebrides trench in the Pacific has revealed that cusk eels and crustaceans teem more than 7,000m (23,000ft) down.

The team used an unmanned lander fitted with cameras to film the deep-sea creatures.

The scientists said the ecology of this trench differed with other regions of the deep that had been studied.

"We're starting to find out that what happens at one trench doesn't necessarily represent what happens in all the trenches," said Dr Alan Jamieson, from Oceanlab at the University of Aberdeen, UK, who carried out the expedition with the National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research in New Zealand.

The team used a lander fitted with cameras and loaded with bait to lure the deep-sea creatures into view

Cusk eels were found at all depths - they may be good at coping in environments where food is scarce

Some of the deep-sea animals, such as this arrow-tooth eel, were brought back to the surface

There are more than 30 deep-sea trenches around the world, and most of these narrow fissures in the seafloor lie in the Pacific Ocean.

Until this expedition, the depths of New Hebrides trench, which sits about 1,500km (1,000 miles) north of New Zealand, had not been explored.

The footage captured by the team during the 30-day voyage at the end of 2013 shows large, grey cusk eels, some 1m-long, chomping on the bait that had been attached to the lander.

The fish mingle with large, bright red prawns scrabbling around on the sandy seabed, which plunges down to 7,200m at its deepest point.

They also spotted eel pouts, arrow-tooth eels and thousands of smaller crustaceans, some of which were collected and brought back to the surface.

However, the team noted marked differences when they compared this trench with others they have studied, which include the Japan trench, the Izu-Bonin trench and the Kermadec among others.

Dr Jamieson said: "The surprising thing was that there was a complete and utter lack of one of the most common deep sea fish we would expect to see. Anywhere else around the Pacific Rim, around the trenches we've looked at, you see a lot of grenadiers - they are quite a conspicuous part of the deep-sea community. But when we went to the New Hebrides trench, we didn't see a single one.

"But what we did see was a fish called the cusk eel. These turn up elsewhere but in very, very low numbers. But around the New Hebrides trench, these - and the prawns - were all that we saw."

There was also an absence of snail fish, a small pink fish usually seen in the deepest depths of ocean trenches.

The researchers believe the differences are driven by how nutrient-rich the region of ocean above the trenches is.

"If you look at the New Hebrides trench, and where it is geographically, it lies under very unproductive waters - there is not a lot happening at the surface of the tropical waters," said Dr Jamieson.

"It seems the cusk eels are specialists in very low food environments, whereas the grenadiers require a greater source of food."

This expedition forms part of a new wave of exploration of the deep ocean.

Almost all of this has been carried out using landers or underwater robots, but in 2012, Hollywood movie director James Cameron made a record-breaking dive to the deepest place in the ocean - the Mariana trench.

He described it as an alien place, devoid of life. This may be because it lies so far from the continental shelf, which means very few nutrients drift down into the trench, which is nearly 11km deep, making food extremely scarce.

But while larger creatures may be absent, scientists recently revealed that microscopic life is plentiful at the bottom of the Mariana trench.

Footage from Earth's deepest place - courtesy National Geographic

Follow Rebecca on Twitter, external

- Published18 March 2013

- Published27 March 2012

- Published26 March 2012

- Published2 February 2012