What are the Northern Lights? And how can you see them?

- Published

The Northern Lights are a stunning display of glowing, swirling lights in the night sky that have amazed humankind for thousands of years.

But what causes them? And how can you see them?

What are the Northern Lights?

The Northern Lights - or aurora borealis - appear as bright, swirling curtains of lights in the night sky and range in colour from green to pink and scarlet.

The Southern Lights - aurora australis - are seen in latitudes near the South Pole.

The lowest part of an aurora is typically 50 miles (80 km) above the Earth's surface. The highest part could be 150 miles (800km) above the Earth.

What causes the Northern Lights?

Both the Northern and Southern Lights are caused by charged particles from the sun hitting gases in the Earth’s atmosphere.

They occur around the North Pole when the solar wind carrying the particles interacts with the Earth’s magnetic field.

The most impressive auroras occur when the Sun emits really large clouds of particles called "coronal mass ejections".

"Picture this as a big sneeze by the Sun," says Dr Affelia Wibisono, from the Royal Observatory in Greenwich. "It can contain up to a million tonnes of charged particles.”

Why have we seen so much of the Northern Lights recently?

What used to be a once-in-a-lifetime event for people to see it in the UK has become more common in the last couple of years. There are a few reasons for this.

The first is that the Sun is reaching a “maximum” in its 11-year cycle. During this maximum, the number of sunspots increases, which leads to more coronal mass ejections (the Sun expelling superheated plasma and magnetic fields) sending charged particles to Earth, creating the aurora.

Also, compared with the last solar maximum in 2014, more of us now have a smartphone to take pictures of the aurora. Plus, apps and social media and a better forecast have a role to play.

What time are the Northern Lights visible?

The Northern Lights can be seen best at night with a clear sky.

“The brightest aurora are typically around 11pm to midnight local time,” according to Andy Smith, a researcher at Northumbria University working on using artificial intelligence to predict space weather.

Be aware that they often won’t look as bright to the naked eye as they do in photos and video. Professional photographers often set their cameras to take in more light and make the displays look more spectacular.

A team of space physicists at Lancaster University runs the social media account AuroraWatch UK on X, formerly Twitter, which lets people know when the Northern Lights might be seen in the UK.

How to photograph the Northern Lights

Setting a long exposure time can capture the aurora but you will have to keep the camera still, ideally using a tripod to avoid blurring.

If using your phone, switch off the flash, set the camera app to night mode and set the exposure time between three and five seconds. Just like with a bigger camera, you will need to keep your phone still.

Some apps may have more advanced camera settings which allow for shutter speed, ISO, and the length of exposure to be adjusted.

Why are there different colours in the Northern Lights?

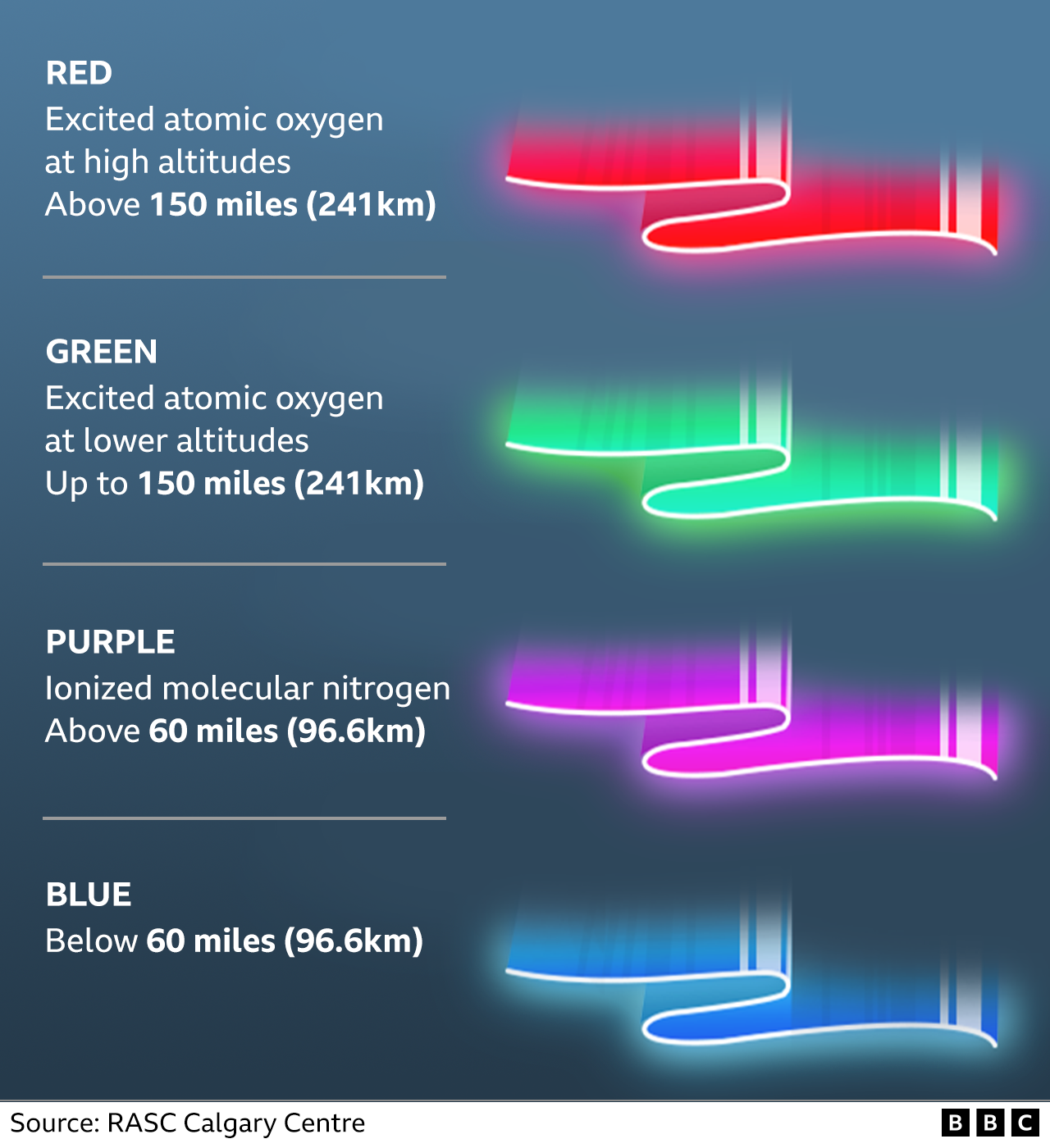

Different gases produce different colours when energised.

The two most common gases in the Earth's atmosphere are nitrogen and oxygen. Oxygen atoms glow green - the colour most often seen in the Northern Lights.

Nitrogen atoms emit purple, blue and pink.

These colours are seen less often because nitrogen atoms are harder to energise than oxygen atoms. Only a really big ejection of solar particles produces this kind of display.

Sometimes the Northern Lights are scarlet. This is the colour seen when oxygen is energised by solar particles at very high altitudes.

Where can you see the Northern Lights?

According to the British Geological Survey (BGS), the Northern Lights are seen most often in regions close to the North Pole such as Scandinavia, Greenland, Alaska, Canada and Russia.

"The bigger the coronal mass ejection from the Sun, the wider the area around the poles in which particles enter the atmosphere," says Prof Jim Wild from Lancaster University. "Then, auroras will be seen in lower latitudes.

“They have been seen as far south as the Caribbean."

Where is the best place to see the Northern Lights in the UK?

The greatest probability of seeing the Northern Lights is in Scotland, Northern Ireland and northern England, according to Met Office space weather manager Simon Machin.

However, in May 2024, they were spotted in several parts of the south of England, including Kent, Dorset and even London.

Which month is best to see the Northern lights?

According to the BGS, there are bigger Northern Lights displays around the equinoxes (March-April and September-October), because there are more magnetic storms during those periods.

The Southern Lights occur just as frequently as the Northern Lights, and are commonly seen across Antarctica.

However, since relatively few people live in latitudes close to the South Pole, they are not as well-known as the Northern Lights.

Is the aurora borealis the same as the Northern Lights?

The aurora borealis is the scientific name for the Northern Lights, named after the Roman goddess of dawn, Aurora, and the Greek god of the north wind, Boreas.

The scientific name for the Southern Lights is the aurora australis after the Greek god of the south wind, Auster.

Where is the best place to go on holiday to see the Northern Lights?

The Northern Lights form in an oval around the Earth’s north pole in an area called the auroral zone.

Areas in the auroral zone include north Norway, Sweden, Finland, Iceland, Greenland, and Canada, the north of American state Alaska, and northern Siberia, in Russia.

This zone will bulge and move depending on the geomagnetic activity but Mr Smith said the most reliable locations are places like Scandinavia, Iceland and Canada.

Image credits: Owen Humphreys/PA Wire, Steve Lomas, Hannah Close/PA, Jo Evans, Jim Hunter Images, Reuters/Alexander Kuznetsov, Stefan Babel, BBC Weather Watchers / Happy Snapper, BBC Weather Watchers / Jonny Gios, Getty Images, Lee Newman, BBC Weather Watchers / David, Alexey Malgavko / Reuters

Related topics

- Published28 February 2014