Citizen science study to map the oceans' plankton

- Published

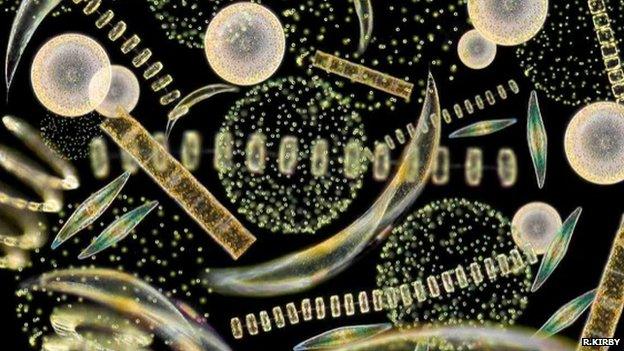

The role phytoplankton plays in life on Earth is often overlooked, says Dr Richard Kirby

A study is calling on the world's sailors to help map the oceans' phytoplankton, microscopic plants that form the bedrock of marine food chains.

Researchers have developed an app for people to submit readings from Secchi disks, external - a method used since 1865.

The team hopes the data will help them understand what is happening beneath the waves.

They have been "astonished" by the response so far but are hoping for more readings from the southern hemisphere.

'Dramatic decline'

"The reason the project came about was because, in 2010, some Canadian scientists wrote a paper that suggested that the phytoplankton in the world's oceans had declined by 40% since the 1950s, external," explained project leader Richard Kirby, a research fellow at Plymouth University's Marine Institute.

"If true, this is a dramatic decline. As phytoplankton starts the food chain, they dictate the productivity at every level above," he observed.

"Ultimately, phytoplankton determines the amount of fish in the sea and the number of polar bears on the ice."

Marine biologists have been using the Secchi disk method to measure the abundance of phytoplankton for 150 years.

The white disk measures 30cm (1ft) in diameter and is lowered into the water on the end of a tape measure. When it is no longer visible from the surface, the reading - known as the Secchi depth - is recorded.

"It is a very robust method and not prone to error and it is a good measure of phytoplankton abundance," Dr Kirby told BBC News.

"Away from estuaries and more than a kilometre from the coast, the main influence on water clarity is phytoplankton."

He explained how he had the idea of setting up a citizen science project: "It occurred to me sat at my desk that while there are a lot of scientists, there are not that many that are marine scientists, and fewer still that go to sea.

"And the ones that do go to sea do not go out very far. If they do go out far, they rarely go back to the same place.

"I thought that there are an awful lot of sailors out there; day sailors, cruising sailors. Many of these sailors will sail the same waters and take the same route time and time again."

All at sea

Dr Kirby, and colleagues Drs Nicholas Outram and Nigel Barlow from the University's School of Computing and Mathematics, developed the Secchi Disk App that would store a reading while at sea before uploading it to a database once the smartphone was back within range of a mobile phone network.

"We can now collect Secchi depth measurements from all over the world's oceans and add that to the data from the 1860s to make a continuous - with a slight dip - record to see what is happening to the phytoplankton in the oceans," he said.

The database, managed by Dr Sam Lavender, is accessible, free-of-charge, from the project's website, external.

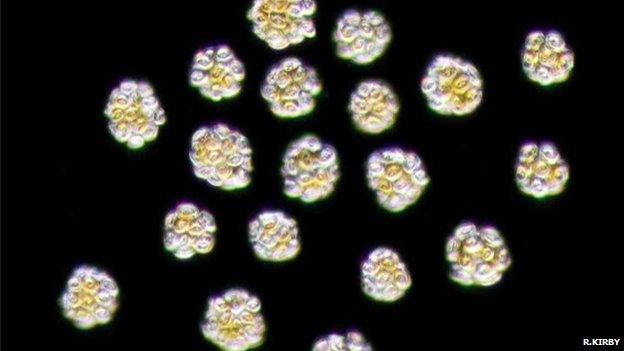

Often mistaken for pollution, foam found on beaches is the decaying remains of vast colonies of phytoplankton commonly known as foam algae

Scientifically, foam algae is known as Phaeocystis globosa - a single-celled organism that forms vast colonies as a result of being bound together with a jelly-like substance

Decaying phytoplankton emits a gas called dimethyl sulphide (sulfide), which is responsible for the characteristic "smell of the sea" and plays a role in cloud formation

The reason for collecting measurements via the Secchi method, Dr Kirby explained, was because the Canadian team's findings proved to be quite controversial among scientists.

"Some said that they did not see any similar decline, while others said they saw an increase rather than a decline," he said.

Feeling the heat

The study was criticised because it combined Secchi disk measurements with data gathered using modern technology that became available to scientists in the late 20th Century.

Despite the criticism, the authors have defended their findings, saying the dramatic decline was a result of sea surface temperature.

"They said that the warming had increased stratification so fewer nutrients were reaching the oceans' surface, and so there was less phytoplankton growth," Dr Kirby said.

He added that in the waters around UK shores, observations showed that phytoplankton were appearing at different times of the year.

He said that changes in the seas' seasons had potential consequences for life beneath the waves.

"This is changing the coupling in the marine ecosystem. Evolutionarily, everything is synchronised - just as it is on land.

"When the timings start altering, even by just a fraction, then things no longer work through the food chain."

To help raise awareness of the vital role phytoplankton plays in marine and terrestrial food chains, Dr Kirby has written and produced a short film called Ocean Drifters, which has been sent to every secondary school in England.

Narrated by Sir David Attenborough, the film also explains how plankton is responsible for the familiar smell of "sea air", and how the tiny organisms are involved in the formation of clouds.

- Published28 July 2010

- Published26 September 2012

- Published10 April 2013

- Published23 February 2013