'Shrapnel' risk to future Moon surface missions

- Published

Before and after images of the same area revealed a fresh 18m-wide crater

The "shrapnel" generated by small space rocks that periodically hit the Moon may pose a larger risk to lunar missions than was previously believed.

A number of countries and private consortia have stated their plans to send robotic and crewed missions to the lunar surface in the coming decades.

A relatively small impact on the Moon last year hurled hundreds of pieces of rocky debris out of the crater.

Many were travelling at the speed of a shotgun blast.

The meteoroid strike sprayed small rocks up to 30km from the initial impact site, said Professor Mark Robinson, from Arizona State University.

He presented his analysis at the 45th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference (LPSC), external in The Woodlands, Texas.

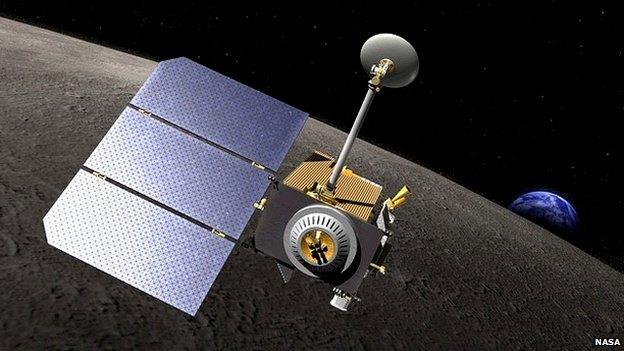

Along with colleagues, he used the LROC imaging instrument aboard Nasa's Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter spacecraft to follow up on observations from 17 March 2013 of an apparent collision on the Moon's surface.

The orbiter took pictures of the area that corresponded to co-ordinates for the impact flash.

Prof Robinson and his team found a fresh 18m-wide crater, punched by a 0.3-1.3m-wide space rock. The crater is surrounded by typical "ejecta" deposits - the continuous blanket of rock and soil heaved out when the meteoroid thumped into the lunar surface.

However, they also saw 248 small "splotches" extending up to 30km from the primary crater. This was further than the typical extent for continuous ejecta deposits from a lunar crater.

LRO was launched to support future manned missions, among other objectives

Prof Robinson interprets these surface splotches as relatively low velocity, secondary impacts into the lunar soil by material flung out in different directions by the primary impact. Using the known facts of the impact, the researchers were able to calculate the energy needed to create the splotches.

"Since they're spread out at great distances, we really need to start thinking that 'secondaries' from small craters pose possibly a larger risk to future long-lived surface assets than the actual primary craters themselves," he told an audience at the LPSC.

"Even though 100m/s is low-velocity, you would certainly not want to be hit with material coming in at 100m/s. That's about the velocity of a shotgun blast."

He said that the LROC team had discovered hundreds of similar splotches around other lunar craters - and that some of these were "directional".

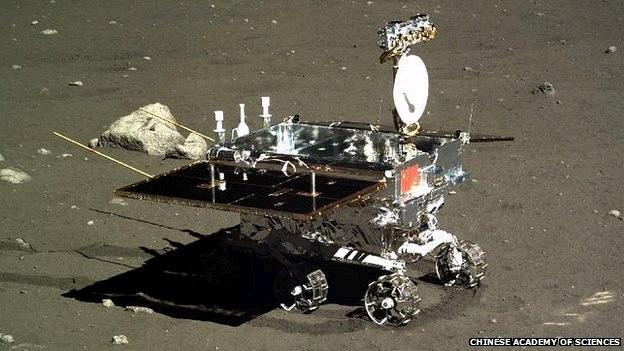

Several countries, including China, whose Yutu rover is shown here, plan to send future missions to the lunar surface

Most of the 33 tonnes of rock that hits the Earth every day burns up high in the atmosphere, never making it to the ground. However, the Moon has only the thinnest of atmospheres, so there's nothing to stop meteoroids from hitting the surface.

There are uncertainties over the rates at which meteoroids of different sizes hit the Moon, but the Lunar Impact Monitoring Program has recorded more than 300 flashes - including this one - since 2005.

The lunar surface remains a high-priority target for exploration by the space agencies of several countries, including not just the US, but China and India. So a better understanding of the risks posed by the lunar environment could be crucial to the success of those missions.

In late 2013, China landed its first robotic rover - Yutu - on the Moon. Not long after landing, the robot suffered a failure, the exact nature of which has not been fully elucidated by the Chinese authorities.

China has also stated its aim of mounting the first human missions to the Moon since the US Apollo programme - something scientists think the country could achieve by the 2020s.

Prof Robinson said the team would soon begin analysing images from Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter of the area on the Moon where a record-breaking impact flash was observed by Spanish astronomers in September last year.

Paul.Rincon-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk and follow me on Twitter, external

- Published24 February 2014

- Published14 December 2013

- Published6 November 2013