Is Japan playing hunger games with climate change?

- Published

The impact of rising temperatures on the world's food supplies is a key issue for climate experts meeting in Japan. But food security is not just about developing countries. As environment correspondent Matt McGrath reports, a changing climate is one of a number of issues pushing Japan towards a food crisis.

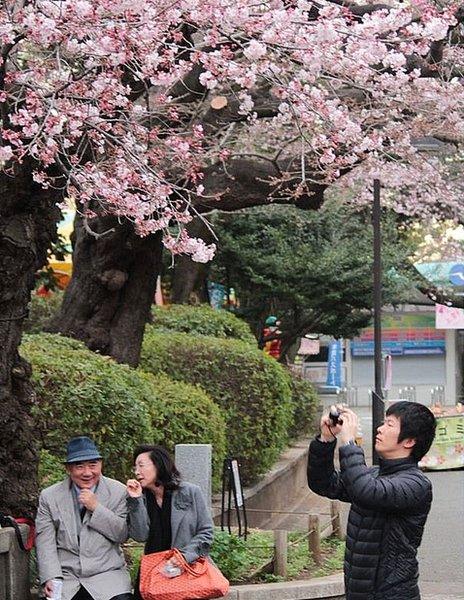

In the historic Ueno Park in the middle of Tokyo, seemingly normal people are earnestly staring at trees.

They are waiting for the first signs of cherry blossom, a spring event of special importance to the Japanese, who will turn out in their thousands to sit under the scented branches and drink themselves squiffy in a custom called Hanami.

But bear hugs from drunken businessmen are a minor threat to the cherries compared to a warming world, according to research.

"There are already reports that the cherry trees are not doing as well as they usually do because the climate is changing," said long time Tokyo resident Martin Frid, who works on food safety issues for the Consumer's Union of Japan.

"They are blossoming at different times, there is now more irregularity."

Because of their cultural significance, the appearance of the blossoms has been recorded in some parts of Japan for over a thousand years.

These records have enabled scientists to work out the impact of global warming on the trees: In recent years they've been blossoming about four days earlier than the long term average.

Experts fear that under some warming scenarios, it could be a fortnight earlier by the end of this century.

While Japan could cope with this change, other impacts of rising temperatures may impose more significant costs.

Waiting for the first signs of cherry blossom is an event of special cultural significance

At his small farm near the city of Ishioka, an hour from Tokyo, Michio Uozumi proudly shows me an inked drawing he made, when starting his organic operation nearly 20 years ago.

It's filled with loving details of compost heaps and free ranging chickens. But his sense of humour shines through, with an illustration of Brazilian soccer stars Pele and Zico, starring on top of one of the pages.

Michio has made most of his field of dreams come true, building a successful small holding and becoming vice president of the Japanese Organic Agriculture Association.

He has also seen changes in the climate first hand.

"Recent early autumns are still summer, with high temperatures," he says.

"Our spinach and other leaves were being hit by insects. We now have to delay their planting by two weeks."

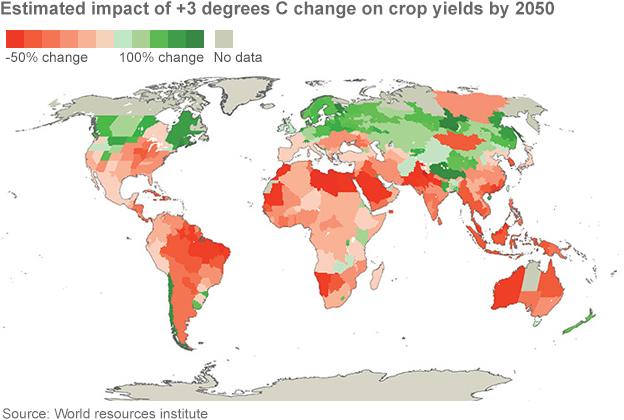

The changes being seen by Michio are likely to become more pronounced according to predictions being discussed this week by scientists at a meeting of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) in Yokohama.

While much of their report is still under wraps, some of the details contained in the chapter on crop yields have been published in a peer reviewed journal in recent weeks.

"We conducted the analysis for the chapter," explains Prof Andy Challoner of Leeds University, one of the IPCC authors.

"But the peer review took a long time, and we were unable to cite it in any way in the chapter, but the numbers are the same."

These numbers, relating to rice, maize and wheat are pretty sobering.

"The aggregate effect is now negative for even a degree or two of warming, which wasn't the case for the 2007 IPCC report," said Prof Challoner.

"Where before we thought there were going to be benefits from a degree or two of warming, this is not the case with the latest data. If anything, we are talking about losing about 5% of yields on average."

Some places will be hit more than others. With populations rising in Africa, the IPCC identify crop productivity there as a key risk.

Much can be done to adapt, says the report. In the near term, with significant efforts and resources, a medium to high risk in many African states can be turned into a low one.

However, wealthier countries could also be facing food risks from climate change that they are not fully aware of, and not taking steps to address.

Michio Uozumi turns leaves and forest litter into a dense, warming compost for his vegetables

"The whole food system (in Japan) is not secure at all, "said Dr Raquel Moreno Penaranda, from the United Nations University in Yokohama.

Japan imports more than 60% of the calories it consumes, she says.

Affluence allows Japan to buy from world markets without concern, but climate change could alter that very quickly.

"We don't know how long these countries are willing to export cheap food to Japan. If that situation changes, you will need to find new suppliers, fast," she explains.

Consumers have also lost trust in the authorities since the Fukushima disaster and several Chinese food scares. Japanese farmers are getting older and their numbers are declining.

"I think we are facing a crisis unless we do something. I think we need a fundamental change in the minds of consumers," says Martin Frid from the Consumers Union of Japan.

"One of the solutions here in Japan is local consumption; local production, where consumers come and help out on the farm and bring their kids."

Michio Uozumi's consumers share some of his workload in return for supplies of vegetables

Back in Ishiko, Michio Uozumi shows me box after box of musty leaves and other forest litter, painstakingly collected by hand from nearby woods.

Containing large amounts of microbes and trace elements, Michio and his family turn the leaves into a dense, warming compost from which they grow a wide range of vegetables all year round. And it cuts their electricity bills to boot.

"The natural organism's power is more powerful than electricity. Many other farmers heat their vegetables but we don't. We refuse to use that, we use our traditional, intelligent and scientific system," he tells me.

Michio's leaves are in fact gathered by some of the 100 consumers who share some of his workload in return for supplies of vegetables and other products.

Avoiding the internet and shunning farmers' markets, Michio's consumers, quite literally have to get their hands dirty to avail of his produce.

"Everyone should contribute something, it is very natural," he explains.

"I suggest to the consumer you should have your own farm, in your farmer. It's about relationships."

Back in Ueno Park in Tokyo, young people are already sitting under the cherry trees, even if the blossoms haven't quite appeared.

Martin Frid takes inspiration from the next generation that the challenges of providing enough to eat in a warming world can be met.

"Kids in Japan don't grow up wanting a car anymore, car ownership among young people is going down, partly because of the environment and the climate," he says.

"The car industry is having a lot of problems, because young people don't see it as a trendy thing to do."

So the key is to make these tough choices somewhat fashionable. Will that work for food I ask?

"Yes," he says.

"It's cool to farm."

- Published26 March 2014

- Published25 March 2014

- Published25 March 2014