Scientists hail synthetic chromosome advance

- Published

- comments

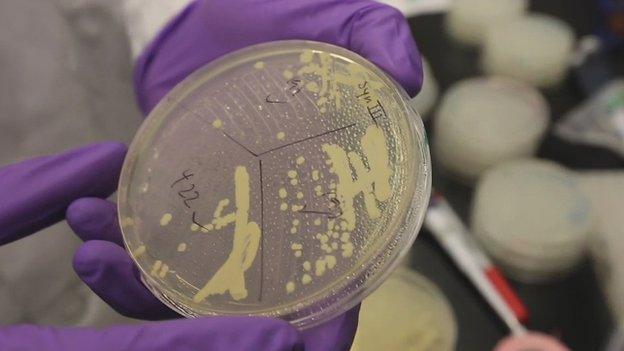

Yeast is a target for synthetic biologists because of its potential for future industrial applications

Scientists have created the first synthetic chromosome for yeast in a landmark for biological engineering.

Previously synthetic DNA has been designed and made for simpler organisms such as bacteria.

As a form of life whose cells contain a nucleus, yeast is related to plants and animals and shares 2,000 genes with us.

So the creation of the first of yeast's 16 chromosomes has been hailed as "a massive deal" in the emerging science of synthetic biology.

The genes in the original chromosome were replaced with synthetic versions and the finished manmade chromosome was then successfully integrated into a yeast cell.

The new cell was then observed to reproduce, passing a key test of viability.

Yeast is a favoured target for this research because of its well-established use in key industries such as brewing and baking and its potential for future industrial applications.

One company in California has already used synthetic biology to create a strain of yeast that can produce artemisinin, an ingredient for an anti-malarial drug.

The synthesis of chromosome III in yeast was undertaken by an international team, external and the findings are published in the journal Science (yeast chromosomes are normally designated by Roman numerals).

Chucking the junk

Dr Jef Boeke of the Langone Medical Centre at New York University, who led the team, described the achievement as "moving the needle in synthetic biology from theory to reality".

In an interview with BBC News, he said: "What's really exciting about it is the extent to which we have changed the sequence and still come out with a happy healthy yeast at the end."

The new chromosome, known as SynIII, involved designing and creating 273,871 base pairs of DNA - fewer than the 316,667 pairs in the original chromosome.

The researchers removed repeated sections in the original DNA and so-called "junk" DNA known not to code for any proteins - and they then added "tags" to the chromosome.

Dr Boeke said that despite making more than 50,000 changes to the DNA code in the chromosome, the yeast was not only "hardy" but had also gained new functions.

"We have taught it a few tricks by inserting some special widgets into its chromosome."

One new function is a chemical switch that allows researcher to "scramble" the chromosome into thousands of different variants making genetic manipulations far easier.

One company has created a strain of yeast that can produce an ingredient for anti-malarial drugs

The hope is that the ability to create synthetic strains of yeast will allow these organisms to be harnessed for a wide range of uses including the manufacture of vaccines or more sustainable forms of biofuel.

While genetic modification involves transferring genes from one organism to another, synthetic biology goes far further by designing and then constructing entirely new genetic material.

Opponents of the field argue that scientists are "playing God" by designing new forms of life with the danger of unexpected consequences. A report for the Lloyds insurance market in 2009 warned that the new technology could pose unforeseen risks.

The synthesis of chromosome III is the first stage of an international project to synthesise yeast's entire genome over the next few years.

A team at Imperial College London is tackling chromosome XI, one of the largest with 670,000 base pairs, using a similar technique of creating "chunks" of bases to insert into the yeast's genome.

New tricks

Dr Tom Ellis, who is leading the work, described the creation of the first synthetic chromosome for a eukaryotic organism - the branch of life including plants, animals and fungi - as a "massive deal".

"Yeast is the king of biotech - and it's great to use synthetic biology to add in new functions.

"The fitness of the chromosome is in line with the natural one. Making all these design changes has not caused any major issues - it behaves as it should - and it's great to see that others can do it."

The Imperial scientists have so far synthesised about one third of the DNA for their chromosome XI with about 5-10% inserted.

Their research includes developing synthetic genes for yeast that would allow it to produce antibiotics and to turn agricultural waste into biofuel.

With critics arguing that synthetic biology involves meddling in Nature with unknown effects, Dr Ellis and others stress that the new organisms are designed with in-built restrictions.

The strains of yeast containing synthetic genetic material can only survive in a lab environment with specialist support.

To highlight the benefits of the work, Dr Boeke stresses the importance of yeast throughout human history and its potential for the future.

"Yeast has an ancient industrial relationship with Man - the baking of bread and the brewing of alcoholic beverages dates back the Fertile Crescent and today the industrial relationship goes far beyond that because we're making medicines, vaccines and biofuels using yeast."

The paper describing the first synthetic chromosome concludes with a far-reaching vision looking beyond yeast to more sophisticated organisms, saying:

"it will soon become feasible to synthesise eukaryotic genomes, including plant and animal genomes".

In his interview, Dr Boeke explained that this will not be immediate but is getting closer.

"It's still aways off in the future to do entire chromosomes for those organisms but certainly mini chromosomes containing tens or even hundreds of genes are definitely within the foreseeable future," he said.

It was only in 2010 that the scientific world was stunned when Dr Craig Venter unveiled the first synthetic genome for bacteria. So this new science is gathering pace and growing in ambition.