Chile lives with quake expectation

- Published

Locals take refuge on the street after the magnitude 8.2 earthquake and the subsequent aftershocks

Chile is one of those countries that expects to experience large quakes.

Tuesday's magnitude 8.2 tremor struck at 18:46 local time (23:46 GMT), at a depth of about 20km. This put the epicentre offshore.

The resulting displacement of the seabed generated a 2m-high tsunami, according to initial calculations.

It's only four years since Chile's 8.8 event at Maule much further to the south. The drivers are the same.

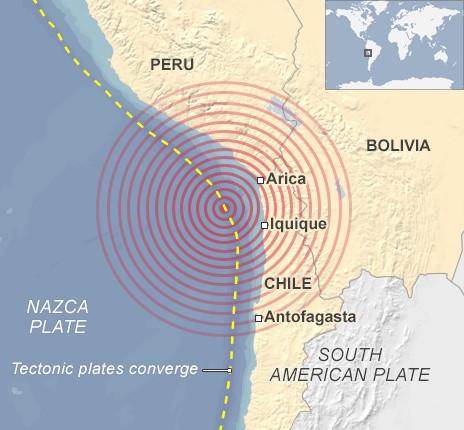

Chile runs along the boundary between the Nazca and South American tectonic plates. These are vast slabs of the Earth's surface that grind past each other at a rate of about 80mm per year.

The Nazca plate, which makes up the Pacific Ocean floor in this region, is being pulled down and under the South American coast.

It's a process that has helped to build the Andes and made Chile one of the most seismically active locations on the globe.

This particular event occurred in what seismologists refer to as the Iquique seismic gap - a segment of the plate boundary that has been relatively quiet in recent times.

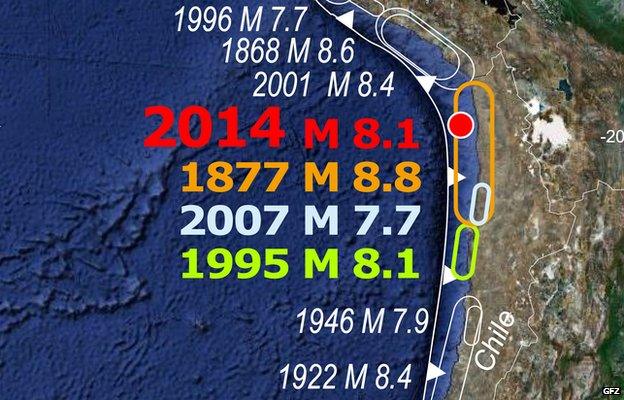

The last big event here was the magnitude 8.8 tremor of 1877, just to the south, which claimed more than 2,000 lives.

"The subduction zone, or plate interface, is highly segmented, so different parts fail at different times," explained Dr Brian Baptie from the British Geological Survey. "This particular segment hadn't failed for over 100 years. So, it is perhaps not a great surprise that a large earthquake has occurred here."

Of course, modern Chilean society should be much better prepared and much more resilient than in the 19th Century.

However, the tremor struck early evening local time on Tuesday, and it is likely that only daylight hours on Wednesday will reveal the true extent of the damage.

Experimental work that makes immediate estimates of probable casualties - based on the quake's characteristics and parameters such as the event region's population size - warned there could be many hundreds of injuries and deaths. Time will tell.

This map from the GFZ German Research Centre for Geosciences lists Tuesday's quake as a magnitude 8.1. It is normal for magnitudes to be refined in the hours, days and weeks following an event

As is always the case, the main 8.2 tremor was followed by a swarm of aftershocks.

Many of these have been fives, but one, a 6.2, hit just 12 minutes after the initial event.

Aftershocks have the effect of further rattling the nerves of already anxious people, but their danger lies in their ability to pull down buildings that have previously been weakened to near collapse.

Seismologists will now be studying this part of Chile intensively, to assess how much strain has been released from the Iquique segment of the plate boundary.

If a large amount of strain remains in the rocks, the segment runs the risk of another big quake at some point in the future.

Historical studies are important also in this respect.

Scientists will want to know if there is evidence in the past of close clustering of major tremors.

In the absence of detailed modern seismological records, researchers must look for this evidence in the rocks themselves.

Phenomena such as tsunamis leave tell-tale traces in the sediments that can be used to date the occurrence of big events thousands of years back in time.

CCTV from inside a supermarket when the tremors struck has been released

- Published2 April 2014