Cities on frontline of climate change struggle

- Published

Half of the world's population now lives in cities - a proportion that's set to rise to two-thirds by 2050. Yet cities are vulnerable to the worst impacts of climate change precisely because their locations are fixed. As the UN's climate panel meets in Berlin, how are urban centres coping with the test?

The latest report, external by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) re-emphasises the vital role cities can play in cutting greenhouse gas emissions. This should come as no surprise, since urban centres are responsible for three quarters of global energy consumption and for 80% of greenhouse gas emissions.

"In a sense, they are the carbon criminals of this world, but they also provide us with really good opportunities," says Prof Tim Dixon from the University of Reading, UK.

One of the ways in which cities can be made greener is through a process called retrofitting. This describes a kind of directed alteration of the built environment to, for example, increase its energy efficiency and reduce energy consumption.

At one level, this might take the form of installing loft and cavity wall insulation, improved boilers, better window glazing or energy-efficient lighting.

But while this already occurs in a piecemeal manner, to be effective, retrofitting must occur on scales greater than individual buildings or even neighbourhoods - there has to be an overarching vision.

"There's no single blueprint that fits every city. But I think successful visions underpin successful cities," says Tim Dixon, who is a researcher on the Retrofit 2050 project, external.

Vancouver on Canada's west coast stands out as a city that has already ventured some way down this path, external.

Vancouver has a well-developed plan for retro-fitting and clear targets

The city wants to limit car journeys, ensuring more trips are made by foot, bike or public transport

The Canadian city involved some 120 organisations and thousands of individuals (through online feedback and face-to-face workshops) in the creation of its Greenest City 2020 Action Plan. The scheme has three overarching areas of focus: carbon, waste and ecosystems.

Among the targets laid out in the document is a pledge to require all buildings constructed from 2020 onward to be carbon neutral in their operation.

Vancouver also wants to halve the solid waste going to landfill over 2008 levels and to ensure more than 50% of trips around the city are made by foot, bicycle or public transport - rather than by car - by 2020.

But in the UK, only a handful of cities have climate change strategies taking them up to the middle of this century.

Of these, few set targets for each sector, such as transport, buildings or public lighting, for example.

But cities such as Bristol and Birmingham have well advanced plans, says Tim Dixon. Bristol's council has drawn up a Climate Change and Energy Security Framework which lays out a strategy for reducing the city's carbon emissions by 40% by 2020 from a 2005 baseline.

It has established a £1.2m energy efficiency fund for non-domestic buildings, has embarked on a programme of installing biomass boilers and solar arrays. It is also planning to build six wind turbines at a site near Avonmouth docks, which would produce enough electricity to power several thousand homes.

Out with the old, in with the new: Las Vegas is replacing its street lights with energy efficient LED lighting

Green roofs can also play their part in visions for eco-friendly cities

"Getting the financing right is key. Urban areas have long lives. In 2050, something like 80% of our buildings are still going to be there," Prof Dixon adds.

"It's not going to be the 1-2% of new stock that is going to be the key focus. It's about taking the longer-term view - looking at how to retrofit those buildings, but also how to protect them.

"You can't unbuild the energy-hungry transport networks, homes and town centres that we've got. There's a huge amount of lock-in. But the challenges are really around how do we develop partnerships within cities, bring together key stakeholders and how do we enable financing to make a difference."

Indeed, the disappointing take-up for the UK government's Green Deal scheme looms large in the memory of those who have a stake in greening our cities. Under the deal, householders could borrow money to install double-glazing, insulation and more efficient boilers.

In March 2013, the government said it expected 10,000 people to have signed up to the programme by the end of that year. But by December, only 1,600 households had applied.

"Looking longer term, I'm sure there's a way the Green Investment Bank could help underpin retrofits at a city scale," says Prof Dixon.

"We need to think creatively and imaginatively. In an era of austerity, it's not going to be the public purse that pays for this, the private sector has to be involved, so we have to think about how we can engage them in these kinds of major energy efficiency measures across cities."

But a balance will have to be struck between strategies aimed at climate mitigation - what we can do to limit or slow further changes - and those based around adaptation - reducing our vulnerability to those effects we can already expect.

David Dodman, an expert on climate change and urbanisation, points out that when word clouds are created from the urban chapters of the earlier IPCC reports, the dominant word is "impacts", while in the 2014 AR5 document it is "adaptation".

"Cities have moved from thinking about how they're going to be affected to what they're going to do about it," says Dr Dodman, from the International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED) in London.

Last year, for example, on the first anniversary of Hurricane Sandy, New York's mayor Michael Bloomberg unveiled a plan to protect the US city, external from climate change-related flooding.

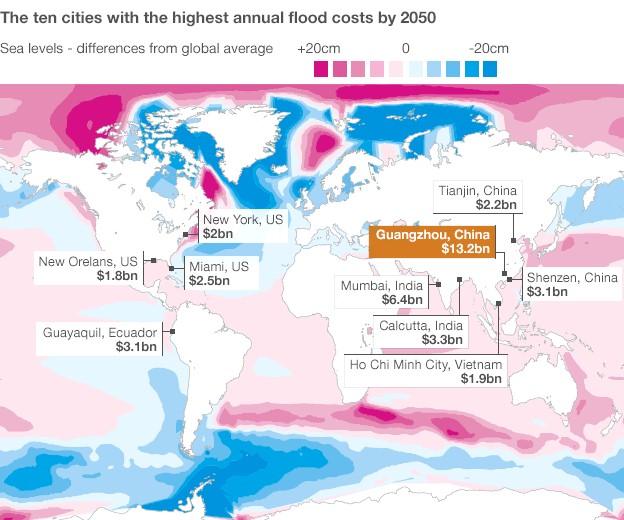

By the middle of this century, a quarter of the city - home to nearly a million people - will lie in flood zones, according to data from the US emergency agency Fema. So the proposals call for the construction of permanent levees and portable storm barriers in order to meet the challenge.

New York has drawn up a detailed plan to protect against future flooding

The plans were announced a year after New York was seriously affected by Hurricane Sandy

New York is an example of a metropolis with the infrastructure, the wealth and the political will to deal with the effects of a changing climate. But David Dodman, an author on the urban chapter in the latest IPCC report, says, large numbers of urban centres in Africa and in parts of Asia are much less well prepared.

"The capacities of those cities [to deal with climate change] are not just to do with knowing what those impacts are, they are much more to do with existing infrastructure, with the financial resources at their disposal, to do with the technical capacity of city governments... and on political governance," said Dr Dodman.

Not every city need respond in the same way as New York to take effective adaptation steps. Coastal urban areas in the tropics could, for example, seed and protect dunes and reforest mangroves to provide protection against future sea level rise.

Dr Dodman uses the term "soft engineering" for such adaptive measures: "It's not quarrying millions of tonnes of concrete to turn into a sea barrier, but more about working with the natural environment," he adds.

Some of Asia's "megacities" like Jakarta, are sinking as the waters rise

The IPCC's working group 2 report says that cities, and particularly those that are rapidly growing, present an opportunity to meet sustainable development goals. This is in part because their institutions and infrastructure are still being developed and there is at least the potential to shape them in ways that are aligned with green thinking.

However, the report also says there is limited evidence of this being realised in practice.

And as the populations of many cities increase, urban communities are springing up in informal settlements, and these groups are often on land that is at a high risk of climate impacts such as extreme weather, and related events such as landslides.

In some cases, several factors may act in concert to amplify changes. Some of Asia's "megacities" - Bangkok, Manila and Jakarta, for example - face a high risk of flooding because of sea level rise, but are also suffering from land subsidence.

This is often due to extraction of groundwater - a resource that will be placed under further stress as the world warms - and also because of the sheer weight of the built environment on alluvial ground.

"They're sinking as the waters are rising," says David Dodman.

For effective climate change adaptation, as for mitigation, coherent visions for future cities will be key.

Follow Paul on Twitter, external.

- Published27 January 2011