Missing plane: Potential 'game-changer' for recovery

- Published

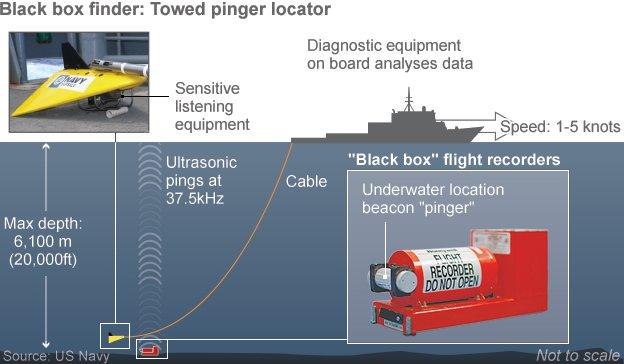

The signals were heard by the towed pinger locator deployed by the Ocean Shield

The news that signals consistent with the missing Malaysia Airlines plane have been detected has been called the most promising lead so far.

Experts are still urging caution at this stage, but if these "pings" detected by the Australian ship Ocean Shield are confirmed a recovery operation could at last get under way.

David Mearns, director of Blue Water Recoveries Ltd, said: "We've gone from little hope to a lot of hope in the space of a day.

"They went from this colossal search area to something very small, and that has been the game-changer. And fortunately they got there in time that the two pingers are apparently still working."

The two signals heard by a pinger-locator towed by the Australian ship are being analysed to see if they are consistent with the flight recorders. They are being prioritised over signals briefly detected by the Chinese search vessel, Haixun 01, over the weekend.

The first step will be for Ocean Shield and the British naval vessel HMS Echo to return to the patch of ocean where they were detected, and to listen again before the data recorders' batteries, which are already nearing the end of their life, run down.

Mr Mearns says: "They'll be working to hear them as long as they possibly can. By continuously criss-crossing over the site, they will refine the position and narrow that down even more. It will give them a pretty precise position of where the wreckage field is.

"HMS Echo will have a pretty accurate fathometer - an echo sounder - to determine the depth. And that is really important."

If this location is less than 4,500m beneath the waves, then Ocean Shield has an autonomous underwater vehicle (AUV) called Bluefin 21 onboard that could be deployed to map the ocean floor.

Dr Simon Boxall, an oceanographer from the University of Southampton, says: "The AUV can use cameras to look at the sea bed, and it has a side-sonar to sweep for wreckage, but you are not getting it live. You have to wait for it to get to the surface to say what it has seen."

If the signal is coming from a deeper spot, a different kind of unmanned vessel would be required. The US Navy and a contractor called Phoenix International have remotely operated underwater vehicles (ROVs) that can dive to depths of up to 6,000m.

Dr Boxall says: "An ROV is tethered to the ship, and that will give you a live feed from the side-scanner sonar and the camera, which means you can focus in on any interesting targets."

Depending on how the plane hit the water, the wreckage field could be spread over hundreds of metres.

A priority would be to locate and recover the flight data recorder and the cockpit voice recorder, which could help to answer what happened to the plane, which disappeared on 8 March. However, other wreckage could also prove crucial to the investigation. For example, it could indicate whether a fire or explosion had occurred onboard.

"An ROV has manipulators. If the black boxes are found, it could use them to bring them back to the surface. Anything bigger and you would have to take cables down and lift stuff up gradually," says Dr Boxall,

It is a process that could take weeks or even months. The seabed in this part of the ocean is not well mapped, but it contains underwater mountains and crevices that could make the task even more challenging. The sea conditions are also difficult: winter in the southern hemisphere is about to begin, and this is an area prone to cyclones.

However, Mr Mearns said while the operation would certainly be complex, it was one that had to happen.

"It makes no difference. They will find the plane. They have the right equipment out there and they will get it," he said.

Follow Rebecca on Twitter, external