UN dilemma over 'Cinderella' technology

- Published

Beccs involves burning wood and other crops, but would require large areas of land

The world's leading climate scientists are considering a plan to remove carbon dioxide emissions from the atmosphere in an effort to stem global warming.

Members of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) meeting here in Berlin, will shortly publish a key study on how to curb rising temperatures.

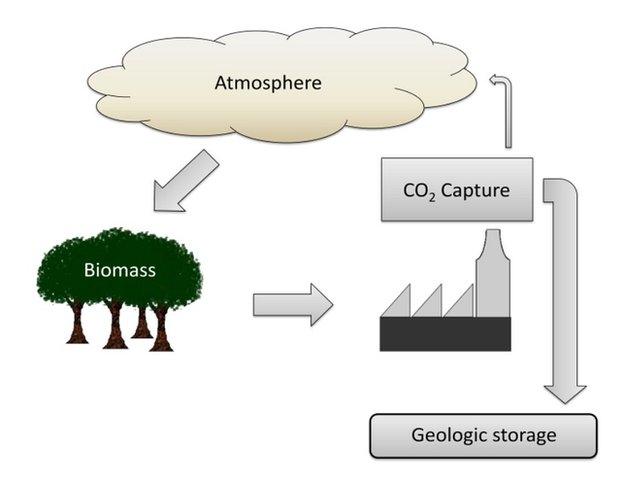

One of the techniques they are considering is a little known method called Bio-Energy Carbon Capture and Storage (Beccs).

But critics warn that the technology is unproven and could give reluctant countries an excuse not to cut emissions.

The idea of capturing carbon dioxide from fossil fuels and storing it underground has been under discussion for over a decade.

The technology has been aimed at large scale, old school power plants that mainly rely on coal as a fuel source.

The idea is to remove the carbon either before or after combustion and pipe it underground so that the invisible gas can be contained in rock formations without leaking.

While CCS could, in theory, limit the amount of carbon going into the atmosphere, it doesn't do much for the CO2 already there.

Some researchers suggested that if you combined the carbon capture and storage with bio-energy crops and plants, you could begin to remove emissions that have already been accumulated.

A handful of pilot operations have been tested, although the technology is hardly known outside a small group of experts.

"I don't know which fairytale figure it is, it may be Cinderella, or Sleeping Beauty," said Henrik Karlsson, from Biorecro, a Swedish company that has been involved in developing a number of Beccs projects.

"But it is facing a long journey to reach a place where this technology catches the interest of the research industry."

That journey may be a little shorter thanks to the interest of the IPCC. At their meeting here in Berlin, scientists and government officials are considering a draft report on the measures that can cut emissions.

Ticking clock

The scientists argue that time is running out for mitigation measures such as substituting renewable energy for fossil fuels. Some ideas on how to remove carbon from the atmosphere are now being discussed.

In a leaked copy of their report, even though there is limited evidence, the idea of Beccs gets a cautious endorsement.

"Combining bio-energy and CCS could result in net removal of CO2 from the atmosphere," it says.

One of the pilot studies took place in France at Artenay, where researchers estimated the amount of carbon that could be siphoned off from a sugar beet refinery.

The beet absorbs carbon as it grows and CO2 is produced in a high quality stream as a by-product of the fermentation process.

A scientist who was involved in the Artenay research, Dr Audrey Laude, says the IPCC are right to consider options like Beccs, as she says it is an insurance policy against dangerous levels of warming.

"Without Beccs the modelling doesn't work to keep us under 2 degrees C," she told BBC News.

"We know there will be an over shoot soon and Beccs is necessary because it gives you negative emissions and that is a way of rectifying the overshoot."

But how much impact can a technology like Beccs really have?

Sugar beet absorbs carbon as it grows and CO2 is produced as a by-product of fermentation

Henrik Karlsson says that in a study carried out by his company in Sweden, you could mitigate all the emissions from the transport sector if you used a Beccs system on all the pulp mills in the country. He is delighted that the idea is being considered at the IPCC.

"We are already in such a bad position that we need all possible mitigation options as well as carbon removal from the atmosphere, and that is the big, big breakthrough of this report from the IPCC, that this is established as a fact," he says.

However there is much unease here in Berlin about the merits or otherwise of removing carbon from the atmosphere.

Several countries, including Germany and China, expressed reservations about the use of technologies like Beccs in their written comments on the IPCC draft.

Campaigners, concerned about the use of land to grow crops for energy, are also worried about Beccs.

They believe that to be effective as a means of removing carbon from the air, it would require huge amounts of land.

"To do Beccs on a large scale you need vast areas to grow crops or trees," said Almuth Ernsting from Biofuelwatch.

"What's become clear with the evidence of biofuels is that such large programmes result in massive ecosystem destruction which releases large amounts of carbon and these land conversions has significant impacts on people too."

Ironically, one of the most promising options for developing Beccs is in tandem with the oil and gas industry. The stream of carbon dioxide that can be separated from the crops being burned or processed can be used to help in the recovery of hard to reach oil deposits.

And it is this close association with fossil fuels that presents many campaigners and scientists with a dilemma over the use of Beccs.

"It gives people the sense that we can get away from burning ever more fossil fuels and this is a wonderful way of getting carbon back out of the atmosphere," said Almuth Ernsting.

"Even if it isn't done, it provides some golden solution out there to justify not cutting emissions."

Certainly there are major issues ahead for the idea. There are question marks over the storage of carbon dioxide underground, there are few government incentives and perhaps most damningly for Beccs, there are few academic or industrial groups interested in developing it.

"We are in a classic valley of death for technologies like Beccs," said Dr Laude.

"There are no incentives and too many risks. Everybody is waiting for the next step."

But Henrik Karlsson remains optimistic - he believes that because it is relatively low-tech, cheap and can be used on a wide variety of industries. More importantly he says, we have run out of time to do anything else.

"The emissions situation is really bad - it is not a moral dilemma it is an actual dilemma," he says.

"Beccs is the only technology currently available that can reverse the trend of emissions in the atmosphere - it makes it a moral obligation to deploy it as soon as possible."

Follow Matt on Twitter, external.

- Published31 March 2014