How does Europe wean itself off Russian gas?

- Published

- comments

European countries are trying to break away from their dependence on Russian gas

Each escalation of the crisis in Ukraine sends a jolt of nervousness far beyond its borders as Europe worries about its energy supplies.

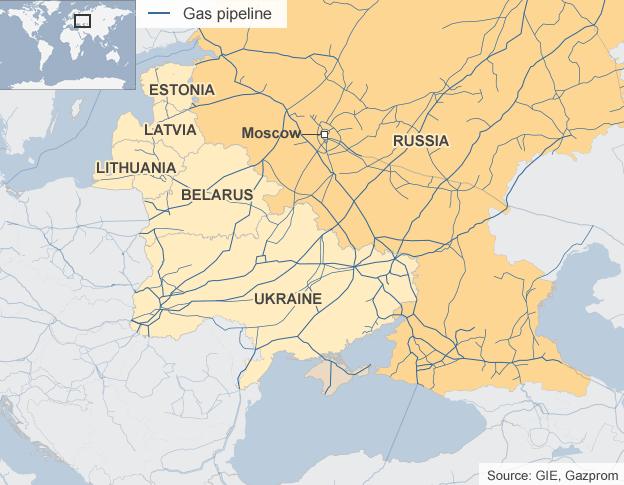

With about one-third of Europe's gas coming from Russia and about half of that gas flowing through Ukraine, these are tense times.

Most worried are the four EU member states which get literally all of their gas from Russia - but another 12 rely on Russia for more than half their supply.

Conversations in recent days - mostly off-the-record - with pipeline operators, energy executives and government officials reveal a series of concerns.

And one phrase keeps coming up to describe what is at stake as energy emerges as a potential weapon: oil is money but gas is power.

If progressively tougher sanctions are imposed on Russia, would President Putin retaliate by closing off the gas taps? Or would that cost Russia too much?

If Ukraine continues to stall on settling gas bills which it regards as unfairly hiked, would Russia starve it of gas?

Talks in Warsaw on Friday between Ukraine, Russia and the EU will attempt to find a settlement.

Russia has increased Ukraine's gas prices by about 80% since February

And if the conflict intensifies to the point where heavy weapons might conceivably be deployed, would pipelines laden with gas have to be shut down for safety? Ukraine is, after all, the world's largest transit country for gas supplies.

These are among the scenarios - some more plausible than others - seizing minds as the rhetoric between the Western powers and Russia becomes more strident.

One line of thought is that both sides have far too much to lose to involve something so vital as energy in the dispute making so all these fears overblown.

After all, gas is one of Russia's most valuable exports and western Europe enjoyed smooth flows of it even in the worst of the Cold War years when the East-West conflict was far more fundamental.

But, even though it is only late spring, a surprising number of figures in the field have cast an anxious eye ahead to the danger of gas stocks running low this winter.

So why are western countries not immediately trying to wean themselves off Russia's gas?

The short answer is that they are trying to - and will discuss ideas at a meeting of G7 energy ministers this weekend.

For Ukraine itself, the quickest option is to buy gas from western suppliers rather than from Russia - and several pipelines have been modified for so-called "reverse flows".

Gas pipelines across Eastern Europe

For example, gas owned by the German energy giant RWE is being sold to Ukraine via pipelines running through Poland and Hungary, and Slovakia has just agreed to join this trade. But the quantities involved could never match Ukraine's needs.

New sources

Beyond that, the hope for many countries is to open up to new sources of gas - especially liquefied natural gas (LNG) which is delivered by ship.

Lithuania is rushing to build an LNG terminal at the port of Klaipeda on the Baltic coast which would allow it to receive gas from anywhere in the world.

As one of the handful of countries totally dependent on Russian gas, Lithuania was prompted by a series of price rises and political uncertainties to decide, back in 2010, to create a new pathway for gas. Events in Ukraine have added more urgency.

To speed up the process, the equipment which will turn the LNG into gas is being installed on a specially-constructed ship, named Independence, being built in South Korea and due to be delivered in November.

To meet a deadline of achieving the first delivery before the end of the year, work on the terminal is going on around the clock, the size of the workforce has been trebled and Lithuania's president regards the project as a national priority.

LNG is also being eyed as an option by Poland, Estonia and Ukraine.

However, because LNG is bought and sold on a global market, shipments from places like Trinidad or Qatar must be competed for - and prices shot up in 2011 when Japan closed its nuclear power stations after the Fukushima disaster.

So the process of switching from Russian gas to LNG will bring a greater sense of security but may come at a higher cost.

Expectations are high that the US will soon add its shale gas to the global market in the form of LNG - but not before next year at the earliest when the first export terminal opens in Louisiana.

Other terminals will not be ready till later in the decade.

So despite pleas from several European leaders, the US gas cavalry will not be able to come to the rescue for quite a while.

A longer-term option is for Europe to develop more gas supplies of its own.

Norway, Britain and the Netherlands - all long-standing producers - may try to do this but it is unlikely that flow rates can be increased by much.

Beyond that, another plan is to develop shale gas in the hope of copying America's shale gas revolution.

But several European countries have come out against fracking because of fears about its environmental impact so progress is slow.

So each idea has drawbacks or involves delays or added costs. But the worse the situation in Ukraine, the greater the chance of energy becoming a target for sanctions or reprisals for sanctions.

And that is bound to accelerate the search for ways to end Russia's dominance of a crucial resource.