Paralysed person 'to walk' at World Cup

- Published

On 12 June, the Arena Corinthians stadium in Sao Paulo, Brazil, will play host to not one, but two historic events.

The first is the opening of the biggest international contest in football, the World Cup.

The other is the debut of cutting edge technology that scientists hope could one day transform the lives of millions of people.

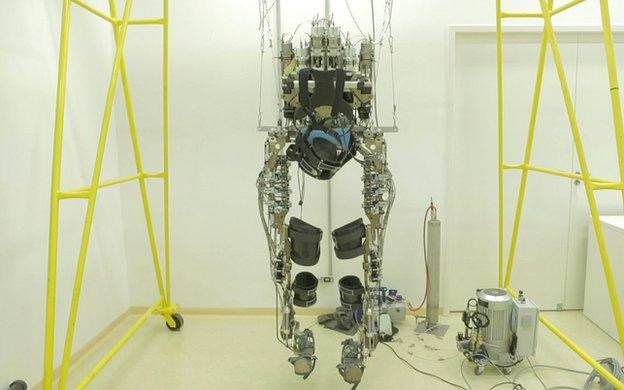

The World Cup curtain-raiser will see the first public demonstration of a mind-controlled exoskeleton that will enable a person with paralysis to walk.

If all goes as planned, the robotic suit will spring to life in front of almost 70,000 spectators and a global audience of billions of people.

The exoskeleton was developed by an international team of scientists as part of the Walk Again Project and is the culmination of more than a decade of work for Dr Miguel Nicolelis, a Brazilian neuroscientist based at Duke University in North Carolina.

In 2003, Dr Nicolelis showed that monkeys could control the movement of virtual arms on an avatar using just their brain activity.

Since November, Dr Nicolelis has been training eight patients at a lab in Sao Paulo, in the midst of huge media speculation that one of them will stand up from his or her wheelchair and deliver the first kick of this year's World Cup.

"That was the original plan," the Duke University researcher told the BBC. "But not even I could tell you the specifics of how the demonstration will take place. This is being discussed at the moment."

Speaking in Portuguese from Sao Paulo, Miguel Nicolelis explained that all the patients are over 20 years of age, with the oldest about 35.

"We started the training in a virtual environment with a simulator. In the last few days, four patients have donned the exoskeleton to take their first steps and one of them has used mental control to kick a ball," he explained.

"So we have realised our objectives: The exoskeleton is being controlled by brain activity and it is relaying feedback signals to the patient."

The robotic suit uses hydraulics and its battery allows for around two hours of use

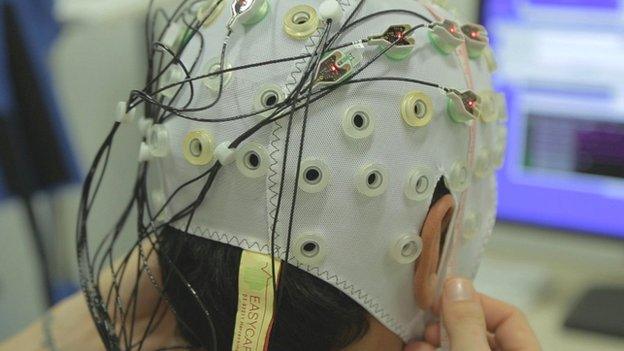

A cap placed on the patient's head picks up brain signals and relays them to a computer in the exoskeleton's backpack that decodes the signals and sends them to the legs. The robotic suit is powered by hydraulics and a battery in the backpack allows for approximately two hours of use.

"The basic idea is that we are recording from the brain and then that signal is being translated into commands for the robot to start moving," explained Dr Gordon Cheng, at the Technical University of Munich, who has been working with Dr Nicolelis and researchers in France to build the exoskeleton.

"I am more on the engineering and technical side, and one of the key technologies we are contributing is a sensor that is the state-of-the-art in artificial skin sensing," Dr Cheng told the BBC.

The sensors on the artificial skin of the robot can sense the environment in a similar way to humans.

"When the foot of the exoskeleton touches the ground there is pressure, so the sensor senses the pressure and before the foot touches the ground we are also doing pre-contact sensing. It's a new way of doing skin sensing for robots," Dr Cheng said.

"The sensor also provides temperature and vibration information and sends all that to a single skin unit."

The suit is able to sense the ground before the foot touches it

Dr Nicolelis explained that "when the exoskeleton starts to move and touches the ground, this signal is transmitted to an electronic vibrator on the arm of the patient. The vibrator stimulates the skin of the patient".

"What happens when you practice for a long time is that the brain starts associating the movements of the legs with the vibration in the arm. So the patient starts developing the sensation that he has legs and that he is walking."

The components of the skeleton were built by "many, many different companies", Dr Cheng told the BBC.

"We are using a lot of 3-D printing technology, which uses materials like very strong plastics, some stronger than metal and very light and, of course, we are using standard aluminium parts. But to reduce the weight and to speed up the development we are using a lot of 3-D printing technology."

Some critics have questioned whether the exoskeleton demonstration could wrongly create an impression that the technology will be available in the near future.

Nicolelis emphasises that "this is just the beginning".

He adds: "Our proposal was always to demonstrate the technology in the World Cup as the first, symbolic step of a new approach in the care of patients with paralysis.

"This is the way science advances. You have to demonstrate and test the concept. It is a way of telling civil society, that pays for science around the world, that we have the possibility to dream with this reality because it is already working experimentally."

So what is the key message that the Brazilian scientist would like to convey to millions of people on the 12 June?

A signal from the brain is translated into commands for the robotic legs

"The main message is that science and technology can be agents of social transformation in the whole world, that they can be used to alleviate the suffering and the limitations of millions of people."

Dr Nicolelis' idea of science as an agent for social change is one of the founding principles behind the research facility he established in 2005 on the outskirts of Natal, in northeastern Brazil, one of the poorest regions in the country.

The Edmond and Lily Safra International Institute of Neuroscience of Natal, ELS-IINN, not only houses research facilities, but also has a science school serving 1.500 children and a clinic providing free pre-natal care with 12.000 consultations each year.

Dr Cheng shares Dr Nicolelis' vision, but says there are many misconceptions surrounding robotics: "I think this exoskeleton is a very beautiful usage. That's what we want to teach children with the outreach that we've been trying to do, to bring the message of science and engineering coming together to make a big difference in society."

"After the demonstration we will continue and then we are going to work out how to get the technology into people's hands. It is going to be within our time. I still have another 20 years before I retire, it's going to be before that."

- Published27 March 2014

- Published4 March 2014

- Published23 September 2011