Colin Pillinger: 'The man from Milton Keynes sending a spaceship to Mars'

- Published

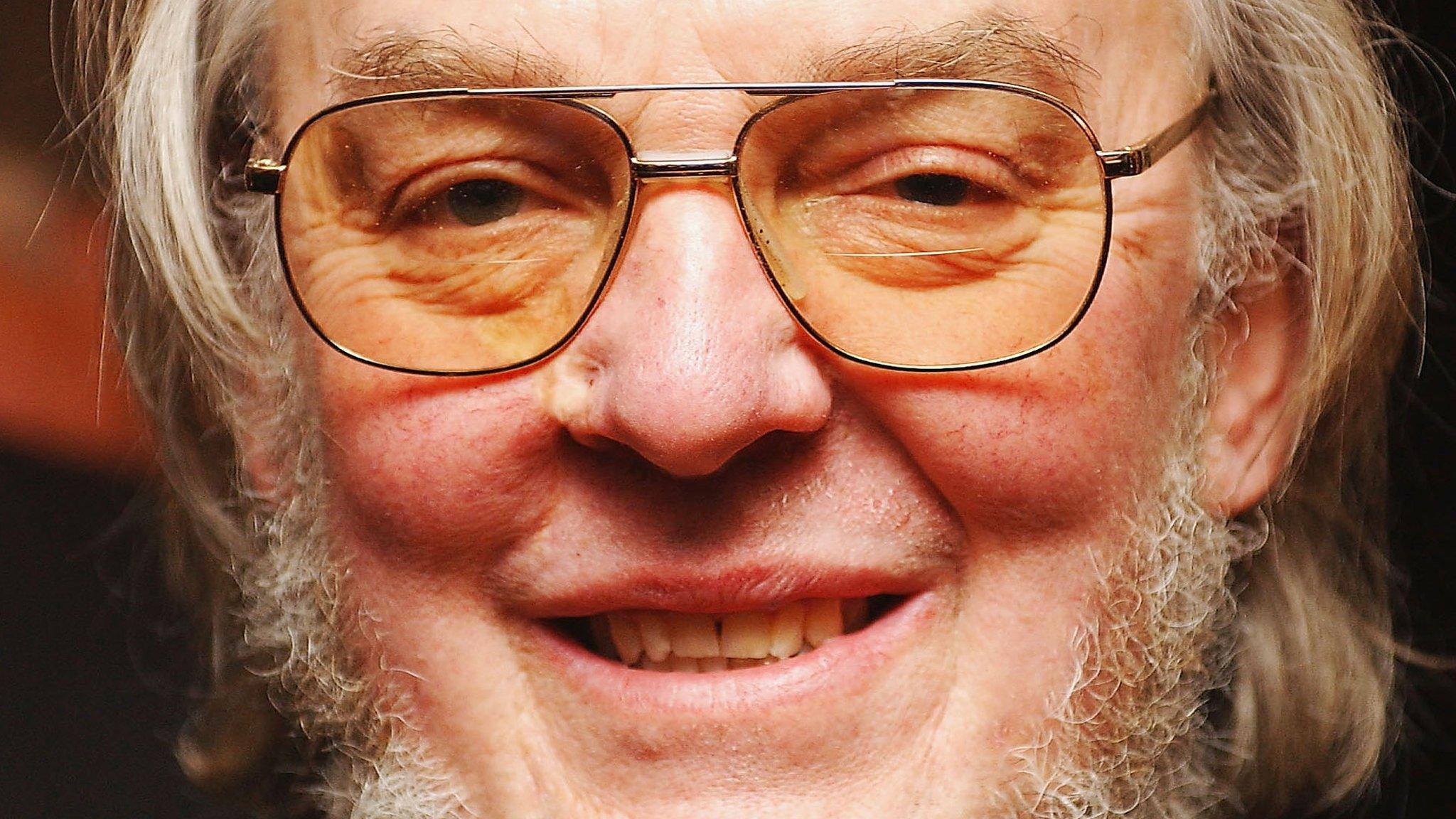

Colin Pillinger: Former professor in planetary sciences at the Open University

The space scientist Colin Pillinger has died at the age of 70. BBC science correspondent Pallab Ghosh looks back at his life.

I first heard about Colin Pillinger 20 years ago when I was a reporter for BBC Look East.

The editor told me about a "bloke in Milton Keynes who is sending a spaceship to Mars".

As you might imagine, I was a little sceptical but, intrigued, I went to the Open University, external to meet him.

I saw him in the distance unfolding what looked like a small barbecue set on a patch of lawn outside his office. It turned out to be a life-sized model of his Beagle-2 probe. It did not look much like a spaceship to me.

Colin greeted me warmly and explained how his proposed Martian lander would work. Such was his enthusiasm that within minutes he had persuaded me that he really could do it.

With his bushy sideburns and Victorian air, he struck me as a modern-day Charles Darwin. He even named his spacecraft after Darwin's research vessel HMS Beagle.

He told me at the time: "We've all looked up at the sky and wondered if life was out there. If we could find life on Mars then you could make the quantum leap and realise that we are not the only living species in the Universe."

Christmas vigil

Indeed, many of us have wondered that, but unlike the rest of us, Colin decided that he was going to do something about it, and he could not see why he should not be able to do it.

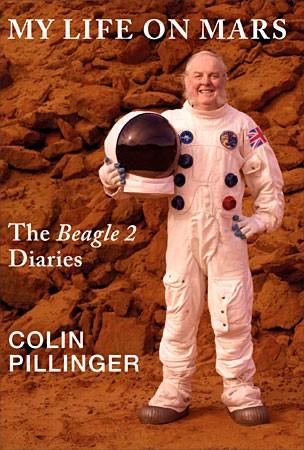

His autobiography's cover featured him in a quarry used to test space technology (Max Alexander)

Space exploration is hard, expensive and carried out by experienced and well-funded national space agencies. An individual researcher had never sent their own vessel into space, let alone to another planet, and so it was through the sheer force of his personality, determination and charisma that Colin managed to persuade the European Space Agency, external to launch Beagle-2 in the summer of 2003.

It was supposed to have landed on 25 December. There was no mission control for the spacecraft because there were no thrusters to control in case its trajectory needed to be altered. Beagle-2 was on a ballistic flight once it had been jettisoned from the rocket that had sent it on its way to Mars. All there was to do as it approached the Red Planet's atmosphere was to cross fingers and wait.

So that is what we all did. Colin had organised a Christmas Eve "vigil" at the Open University's offices in Camden Town in London. Journalists, scientists and celebrities gathered, and stayed overnight waiting for Beagle instead of Santa.

Alex James and Dave Rowntree of the 1990s Brit pop band Blur popped in to wish Colin well over a glass of mulled wine. TV presenter Myleene Klass came, too, offering jelly babies to the assembled crowd.

The combination of glitterati, Christmas and a Martian landing made for a heady cocktail. It was as if we were all five again, unable to sleep or contain our excitement as Christmas morning approached - which was when Beagle was supposed to have landed and sent back a signal. All of us except Colin. His usual enthusiasm made way for a steadfast calm.

Dogged determination

When the news came through that no signal had been received from the spacecraft, the exuberance evaporated and many of us were left completely flat. But Colin barely missed a beat when he announced with steely determination that it was now time to begin the search for the spacecraft.

His enthusiasm was infectious

"In this mission, our faith has been unshakable that this mission would go ahead. We've crossed lots of bridges to get this far and we will keep that unshakable faith," he said.

Orbiting satellites and ground-based telescopes scoured the Martian surface. The public followed every twist and turn of the search for weeks, as if it was some beloved lost pet. It was, of course, never found but Colin was dogged, even in failure.

In 2005, the prof told me he had Multiple Sclerosis. He was on crutches, but had not lost any of his zeal. He showed me a scale model of his next attempt to send a probe to Mars - Beagle-3. It would incorporate a rover that would roll out merrily when he opened a little hatch.

Without thinking I asked him, as we sat down, whether his illness might slow him down. He reached over with his crutch and gave me several sharp pokes.

No joke

"Lobbying space agencies is about meetings and I can always reach you with my crutch if I need to prod you," he said with devilish glee. And always looking to the positives, he added: "So I have an advantage. People cant get that far away from across the table if I want to make a point."

The story of Colin Pillinger and Beagle-2 is in my view often misrepresented as one of heroic, typically British failure, along the lines of the British Ski Jumper Eddie the Eagle.

For me, it is a story of human triumph.

His Beagle-2 spacecraft was cheap and cheerful, but it was not a joke. It was brilliantly engineered by Colin and his team and ahead of its time. The next European landing mission to the Red Planet, called ExoMars, draws on many of Beagle's ideas.

Although Colin was not successful in landing his 2003 probe, his efforts inspired the nation and introduced a new generation to the wonders of space.

I shall miss him but I shall remember him as someone who reached for the stars and persuaded those around him that they could, too.

Follow Pallab on Twitter, external

- Published8 May 2014