Brazuca: Secrets of the new World Cup ball

- Published

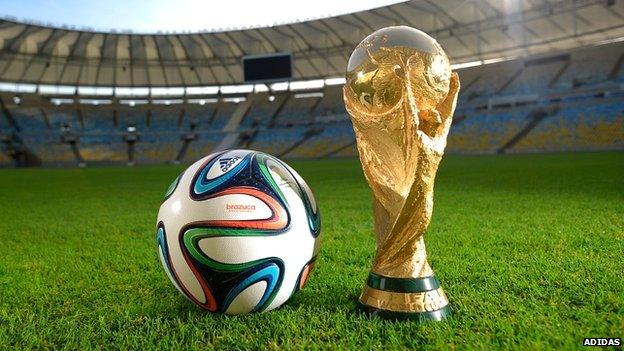

Adidas says the new official football has improved touch and accuracy

It's one of the stars of the World Cup - the paintbrush with which the world's greatest footballing maestros must create their art.

But is it up to the task? The Brazuca, the official ball of Brazil 2014, is the 12th ball created by Adidas for the World Cup.

The company came under fire four years ago for the Jabulani, the official ball at the 2010 competition in South Africa, which was heavily criticised.

"It's trajectory is unpredictable," claimed Italian goalkeeper Gianluigi Buffon, while Brazilian striker Luis Fabiano branded it "supernatural".

Adidas claims the Brazuca has improved touch and accuracy.

"We do extensive flight path analysis and the results have shown constant and predictable paths, with deviations hardly recognisable," Adidas's football director Matthias Mecking told the BBC.

Experts in aerodynamics interviewed by the BBC outline three factors that are expected to influence how the official ball of Brazil 2014 will behave.

"The most important thing on the soccer ball is how much roughness you have," explained Dr Rabi Mehta, branch chief at the US space agency's (Nasa) Ames Research Center in California, and an aerodynamics expert.

The amount of roughness, he explains, "dictates what the critical speed is going to be at which you get maximum 'knuckling' of the ball".

He tested the Jabulani in a wind tunnel and has been looking at the Brazuca. The so called "knuckling effect" occurs when the ball does not spin or spins very little.

Dr Mehta explains that when a relatively smooth ball with seams flies through the air without much spin, the air close to the surface is affected by the seams, producing an asymmetric flow. This asymmetry creates forces that can suddenly knock the ball, causing volatile swoops.

But "when the ball is spinning you get the Magnus effect that makes the ball curve", he explains.

"It's spin-induced side force. So when you see these banana kicks around the wall - for the free kicks like Bend It Like Beckham... that is exactly the Magnus effect."

It is the knuckling effect and the smoother surface of the Jabulani, compared to the Brazuca, that explains its unpredictability, according to the Nasa engineer.

Older, traditional balls that have been internally stitched with the standard 32 panels "knuckled" at around 48 km/h (30 mph).

"The smoother you make the ball, the higher the speed at which it knuckles," says Dr Mehta.

"In essence what happened in my opinion is that with the traditional ball, the critical speed at which you got maximum knuckling was lower than the typical kicking speed in World Cup soccer.

"By making the ball smoother, that critical speed went up and happened to coincide with the typical kicking speeds, about 50, 55 mph (80, 88 km/h), especially in free kick situations."

Brazilian striker Luis Fabiano (L) described the 2010 World Cup's Jabulani ball as "supernatural"

By making this year's ball rougher, according to Dr Mehta, "we're back to square one".

The texture of the Brazuca is rougher. "They have what I would call tiny little pimples, which also would help in terms of the aerodynamics," says Dr Mehta.

"If you compare this to the Teamgeist (the official ball at the 2006 World Cup in Germany), the areas apart from the seams were very smooth. The rougher texture would also help solve other issues, like when you kick the ball there is more friction between the boot and the ball."

But the major factor influencing the roughness is the geometry of the ball's seams.

"Seams are important because they determine to a large extent the roughness of the ball," Dr Mehta told the BBC.

The Brazuca has six thermally bonded propeller-shaped panels, less than the eight of the Jabulani, the 14 of the Teamgeist or the 32 of traditional footballs. Adidas says the new seam geometry will give the ball aerodynamic accuracy and a stable flight.

Fewer panels could actually make the ball smoother, but new ball's roughness is increased in other ways, says Dr Simon Choppin, a research fellow at the Centre for Sports Engineering Research at Sheffield Hallam University, who has measured the seams of the Brazuca.

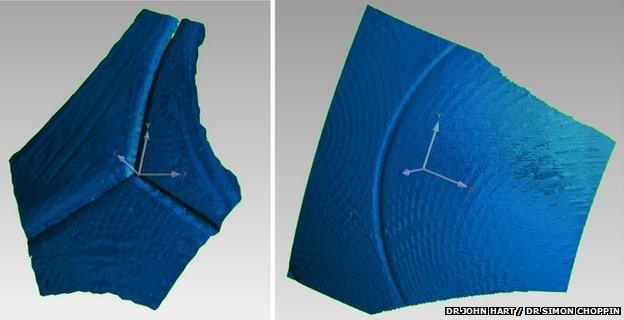

The Brazuca (L) has different seam geometry to that of the Jabulani ball (R)

"A colleague of mine, Dr John Hart, scanned the surface of the Brazuca and the Jabulani using a laser scanner. This gave us a 3-D model of the balls' seams to measure and analyse," Dr Choppin explains.

"We found that the depth of the Jabulani's seams is around 0.48 mm, while the new Brazuca football has seams 1.56 mm deep - more than three times deeper.

"In addition, I measured the lengths of the seams on each ball by tracing them with string. The total length of the seams on the Jabulani is around 203cm and around 327cm on the Brazuca. Not only are the seams on the Brazuca deeper, but they're longer too."

For Simon Choppin, the deeper and longer seams of the Brazuca, compared with the Jabulani, make it more like a traditional stitched football - and wind tunnel tests back up this assertion.

Rougher balls also travel further. As a football flies through the air, its seams stir and agitate the air - like the dimples do on a golf ball or the fluff on a tennis ball, explains Dr Choppin.

"This agitation is essential for fast and reliable flight. A perfectly smooth ball experiences large amounts of drag and high aerodynamic forces."

He added: "The seams of a football disturb the flow of the air.

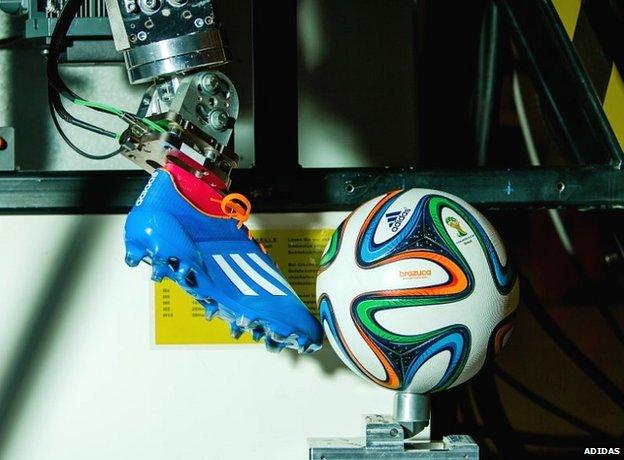

Experts have carried out extensive tests on the new ball

"This results in a smaller wake-area of low pressure - behind the ball - reducing the pressure difference and reducing the force, which slows the ball down. The lower drag force means the ball travels for a longer distance."

So what was the final verdict of the scientists?

"I am pretty sure the Brazuca is going to behave more like the traditional 32-panel internally stitched ball, so the complaints we got in the last two World Cups will be minimised," says Rabi Mehta.

For Simon Choppin, "the seams are more effective agitators of the air, so the knuckling effect is less likely to occur at high speeds. I think the Brazuca will be more stable at high speed than its predecessors".

Dr Mehta says it's the knuckling effect that makes life difficult for goalkeepers.

"What the players have figured out is that it is better to kick the ball with no spin or little spin," he says.

"They've been doing it for years, ever since I was a kid I saw some players kick it with their toes so that it doesn't spin much and that's trying to get the knuckling effect.

"For the Brazuca, the critical speed to get maximum knuckling effect is around 30mph (48km/h). For the Jabulani it was more like 50mph (80km/h).

"So if the players are sitting there listening to me they should not kick the ball as hard now compared with 2010."

- Published2 September 2010

- Published4 June 2010