Turtle migration driven by hatchling drift experience

- Published

The study should inform more effective conserve strategies

Why do turtles migrate to the places they do? What is it that tells them where to swim as adults?

New research is providing some insight, suggesting the animals' experiences as little hatchlings adrift in ocean currents have a huge influence.

Scientists combined all the available satellite tracking data on adult turtles with models of how the world's sea water moves.

It shows that locations encountered in the earliest years are a powerful draw.

If these foraging sites are favourable and not too distant, the turtles will swim directly back to them as adults, time and time again.

If they are not suitable locations, the adults may simply not undertake migrations and just feed in the open ocean.

On their own: When a hatchling heads out to sea, there is no experienced turtle to follow

"The kind of information we're acquiring is important for designing effective conservation strategies," said Dr Rebecca Scott, who led the study soon to be reported in the journal Ecology, external.

"We can't protect turtles in their feeding areas if they're going to lots of different locations and we don't really understand why they're going to those places," she told BBC News.

Many animal groups undertake great migrations, and the process of learning where to go on these travels can take several forms.

For some species like the great whales, the mother shows her calf the way. And for some bird species, the young will learn the necessary flight routes by following at the rear of the flock.

But neither of these strategies works for turtles. Once the adult female has laid her eggs on a beach, her involvement in her offspring's development is ended.

And when the hatchlings run down the beach into the water, they are on their own; there is no experienced turtle to follow, and they go where the ocean takes them.

The difficulty of affixing satellite-tracking tags to neonate (baby) turtles means the data on where precisely they venture in their early years is very sparse.

But scientists can get a good idea by looking at the flow patterns of ocean water moving past nesting sites.

Dr Scott and colleagues used this information to build a picture of the likely drift patterns of the hatchlings.

They then compared this view with the ample sat-tracking data that does exist for adult turtles.

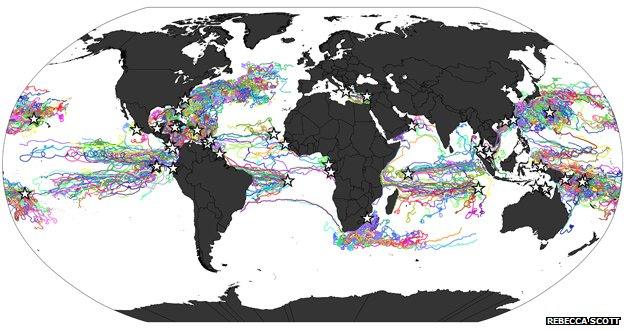

The study incorporates ocean current information from drifter buoys (coloured tracks) passing close to turtle nesting sites (stars)

The synthesis strongly suggests that adult sea-turtle migrations and the selection of foraging sites are closely tied to the past experiences of drifting hatchlings.

The big difference of course is that the adults do not drift - they swim more or less direct.

Scientists would like to find a technique to directly track hatchlings from the beach

"Hatchlings' swimming abilities are pretty weak, and so they are largely at the mercy of the currents. If they drift to a good site, they seem to imprint on this location, and then later actively go there as an adult; and because they're bigger and stronger they can swim there directly," explained Dr Scott.

"Conversely, if the hatchlings don't drift to sites that are suitable for adult feeding, you see that reflected in the behaviour of the adults, which either do not migrate or they feed [in the open ocean], which is really not the normal strategy for most turtle species."

Dr Scott is currently affiliated to the Geomar Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research in Kiel, Germany, but was formerly at Swansea University, UK.

Commenting on the study, Prof Brendan Godley from Exeter University told BBC News: "This is a study of great scope using recently developed oceanographic models as well as tracking data from a large number of oceanic drifter buoys to model the routes hatchling turtles might take from a large number of sites around the world.

"The location of adult turtle foraging grounds discovered by satellite tracking correlates with the expected patterns of hatchling movements.

"It is clearly an incremental step forward, highlighting how the combination of high-tech methods can give us real insights into the enigmatic life cycle of marine turtles. In the long term, however, we need to find techniques which allow us to track hatchling turtles from the beach without impediment. Hopefully, this is not too far over the horizon."

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external

- Published25 March 2014

- Published5 March 2014

- Published27 December 2013

- Published27 June 2012