Ukraine crisis sends a chill into orbit

- Published

- comments

The latest Soyuz landing was a model of international co-operation

A Soyuz capsule returned to Earth on Wednesday with its international cosmonauts.

Russian Mikhail Tyurin, American Rick Mastracchio and Japan's Koichi Wakata had spent 188 days orbiting the planet on the International Space Station.

As is customary, the trio were lifted out of their craft and put in chairs. Thumbs-up and smiles all round. The picture of co-operation.

But the space programme is increasingly wearing a frown also, as the fallout from Russia’s annexation of Ukraine’s Crimea touches all aspects of international relations.

And not even 400km above the Earth, it seems, can you escape geopolitics.

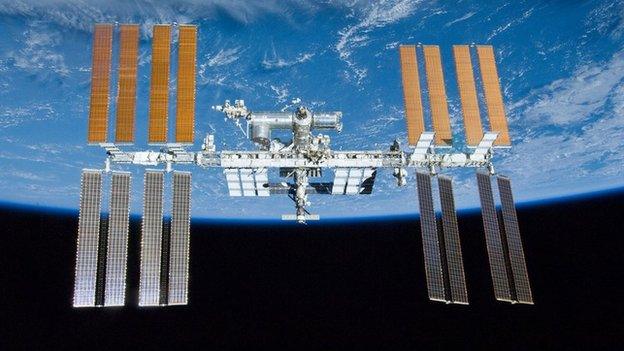

For the moment, the orbiting platform continues to sail serenely around the globe at 27,000km/h, but on Earth things are a little bumpier.

A series of tit-for-tat gestures is raising tensions.

The US put restrictions on its federal officials meeting with their Russian counterparts, and banned some technology exports.

The Russians and Americans depend on one another to operate the ISS

This could have had a major impact on the US space agency (Nasa) and its dealing with its Russian counterpart, Roscosmos, but the White House said matters relating to the space station were exempt, and that’s where most co-operative activity between the pair takes place.

Now, the Russians have hit back by saying they will stop the export of rocket engines to the US if they're to be used to launch American military hardware – something they routinely do when attached to the first-stage of the Atlas rocket.

Several of these vehicles a year will loft spacecraft for the US Air Force or the National Reconnaissance Office (NRO).

Russia is also threatening to shut down monitoring stations on its soil that support services based on American Global Positioning System (GPS) satellites, although Moscow says this is more directly a response to Washington's refusal to allow stations to be built on US soil to support Glonass, the Russians' own sat-nav network.

There's talk, too, of Russia perhaps not agreeing to extend space station operations beyond 2020 – something the rest of the international partners on the project would like to do.

Stirring the pot is Russia’s deputy Prime Minister, Dmitry Rogozin, who is in charge of space and defence industries.

US Atlas rockets currently use a dual-nozzle, Russian-built RD-180 engine to get off the pad

And he really likes to stir. Follow his Twitter feed, external and you'll see what I mean.

When the US introduced its technology sanctions, he wrote, external: "After analysing the sanctions against our space industry I suggest the US delivers its astronauts to the ISS with a trampoline. US Lets Down Its ISS Astronauts By Sanctions Against Russian Space Programme." He even posted a picture of trampoline with a Nasa badge.

It's a joke playing on the fact that the US must now buy seats in Russian Soyuz capsules if it wants to get its astronauts to the space station. After the retirement of the shuttles in 2011, there is currently no home-grown alternative.

A lot of this is huff and puff, of course. But the Russians need to be careful.

They are currently earning a tidy sum out of the Americans. The export of RD-180 rocket engines for the Atlas vehicles is worth hundreds of millions of dollars a year to the Russian space industry. And every one of those Soyuz seats to the ISS is bought for a ticket price that exceeds $60m.

Sabre rattling risks these profitable endeavours.

Already, there are noises in the US Congress that money should be made available to American industry to help design and build an indigenous Atlas first-stage engine.

And circling is Elon Musk of California’s upstart SpaceX company, which wants to sweep all before it by substituting both the Atlas and the Soyuz with the highly competitive Falcon rocket. All Musk's technology is US-built and a lot cheaper to boot.

The Russians therefore have much to lose, financially. But perhaps the saddest aspect of all this is that space endeavour should be touched at all.

It was of course in orbit that the US and the Soviet Union first defrosted relations with the Apollo-Soyuz docking in 1975, external. That co-operation was then built on with the highly successful Shuttle-Mir programme, external, which saw the American orbiters visit the old Russian space station throughout the 1990s.

And today we have the ISS - a shining star for international unity, with astronauts and cosmonauts of many nationalities – not just American and Russian - working very effectively side by side.

That's not something anyone should want to sully.