How much money can we make from fracking Britain?

- Published

Fracking is already used as a method of extracting gas and oil from the ground in several areas in America, as is the case with this site in Texas

How much money can be made from trying to extract oil and gas from the layers of shale that lie beneath Britain?

Answering that is proving to be a surprisingly difficult scientific question because knowing the basic facts about shale is not enough.

The layers have been well mapped for years. In fact until recently geologists tended to regard shale as commonplace, even dull - a view that has obviously changed.

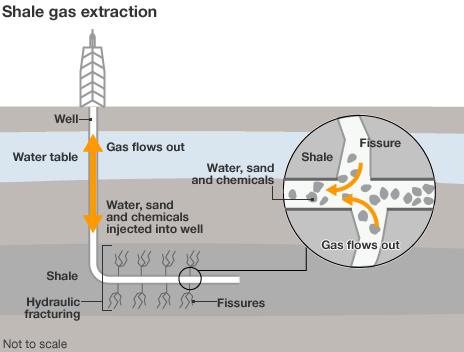

The key tool is a seismic survey: sound waves are sent into the ground and the reflections reveal the patterns of the rocks. This describes where the shale lies but not much more.

'Richer'

So we know, for example, that the Bowland Shale - which straddles northern England - covers a far smaller area than the massive shale formations of the United States but it is also much thicker than they are.

That may mean that it is a potentially richer resource or that it is harder to exploit. Britain's geological history is long and tortured, so folds and fractures disrupt the shale layers, creating a more complex picture than across the Atlantic.

To assess what the layers hold involves another step: wells have to be drilled into the rock to allow cores to be extracted so the shale can be analysed in more detail.

As Ed Hough of the British Geological Survey told me: "We know the areas under the ground which contain gas and oil - what we don't know is how that gas and oil might be released from the different units of rock and extracted.

"There's a lot of variability in these rocks - so their composition, their history and the geological conditions all come into play and are all variable."

Bubbles rise from samples of shale rock - proof that gas exists within them

That means that neighbouring fracking operations might come up with very different results.

In a lab at the BGS near Nottingham, I'm shown a simple but effective proof that shale does contain the hydrocarbons - gas and oil - at the heart of the current surge in interest.

A few chunks of the rock are dropped into a beaker of water and gently heated until they produce tiny bubbles which rise like strings of pearls to the surface.

It is a sight which is both beautiful and significant - the bubbles are methane, which the government hopes will form a new source of home grown energy.

'Deep underground'

The gas and oil were formed millions of years ago when tiny plants and other organisms accumulated on the floor of an ancient and warm ocean - at one stage Britain lay in the tropics.

This organic matter was then compacted and cooked by natural geological warmth which transformed it into the fuels in such demand now.

So one question is the "total organic content" of the shale - how much organic material is held inside - and there can be large variations in this.

But establishing that the shale is laden with fossil fuels is only one part of the story. The samples, extracted from deep underground, then need to be studied to see how readily they would release the fuels.

So the BGS scientists fit small blocks of the shale into devices that squeeze it and heat it - trying to mimic the conditions that would be experienced during a fracking operation, when high pressure water and chemicals are injected into the shale to break it apart.

Understanding how the shale behaves is essential to forming a judgement on how lucrative it might prove to be - or how unyielding or difficult, as some shale can turn out to be.

Dr Caroline Graham, a specialist in geomechanics with the BGS, explained what the research into the rock samples was trying to achieve:

"We'll be able to understand better how likely they are to produce certain amounts of gas, how easily they will frack and therefore it will give us a far better idea of how viable the UK deposits are economically speaking."

These are early days for the science. And hopes that Britain will be able to copy America's shale revolution may be unrealistic.

A senior executive from a global energy company once said a decision on whether to exploit a new shale "play" or area would only be made after 40-60 exploration wells had been dug.

Professor Paul Stevens, an energy expert with the Royal Institute for International Affairs, said:

"It's going to take a lot more wells to be drilled and a lot more wells to be fractured before we even get an idea of the extent to which we might expect a shale gas revolution and over what time period."

So establishing that British shale is rich in oil and gas is only one step of a long journey. The current state of the science only goes so far. How much money can be made from trying to extract oil and gas from the layers of shale that lie beneath Britain?

- Published8 May 2014

- Published20 May 2014