Will a new climate fund unlock a global deal?

- Published

Wind energy projects in emerging economies have proven more popular than adaptation

As UN climate talks continue in Bonn, money is emerging as a critical element in getting the world to agree on a new deal by the end of next year.

It must have seemed like a really neat development idea back in the mid-1990s.

The Philippines government had no way of disposing of medical waste in their hospitals.

And the 26 incinerators from Austria seemed like good value, especially as the Bank of Austria and the Austrian government were offering finance upfront in the form of a development loan.

Just a few small drawbacks.

When the incinerators were shipped to Manila, they were already banned in the European Union because of their polluting effect.

Then the air quality laws changed in the Philippines as well.

And the exhaust plumes from the new incinerators were found to be 870 times above one environmental standard.

By 2003 they were all scrapped - but the Philippines had to continue paying back, external $2m per annum in loans for many years afterwards.

While this was money for development, campaigners are equally concerned about finance for climate change, says Lidy Nicpal, a climate campaigner with Jubilee South.

"What it has done to our national government's finances is an accumulation of so many loans that we are now paying back, which has not resulted in any clear improvement in our development," she said on the fringes of UN climate negotiations in Bonn.

Money, or the lack of it, is shaping up as a critical plank of any prospective climate agreement, external come December 2015.

Scientists, politicians and campaigners alike acknowledge the huge importance of getting a new deal in place, if the world is to avoid dangerous levels of warming.

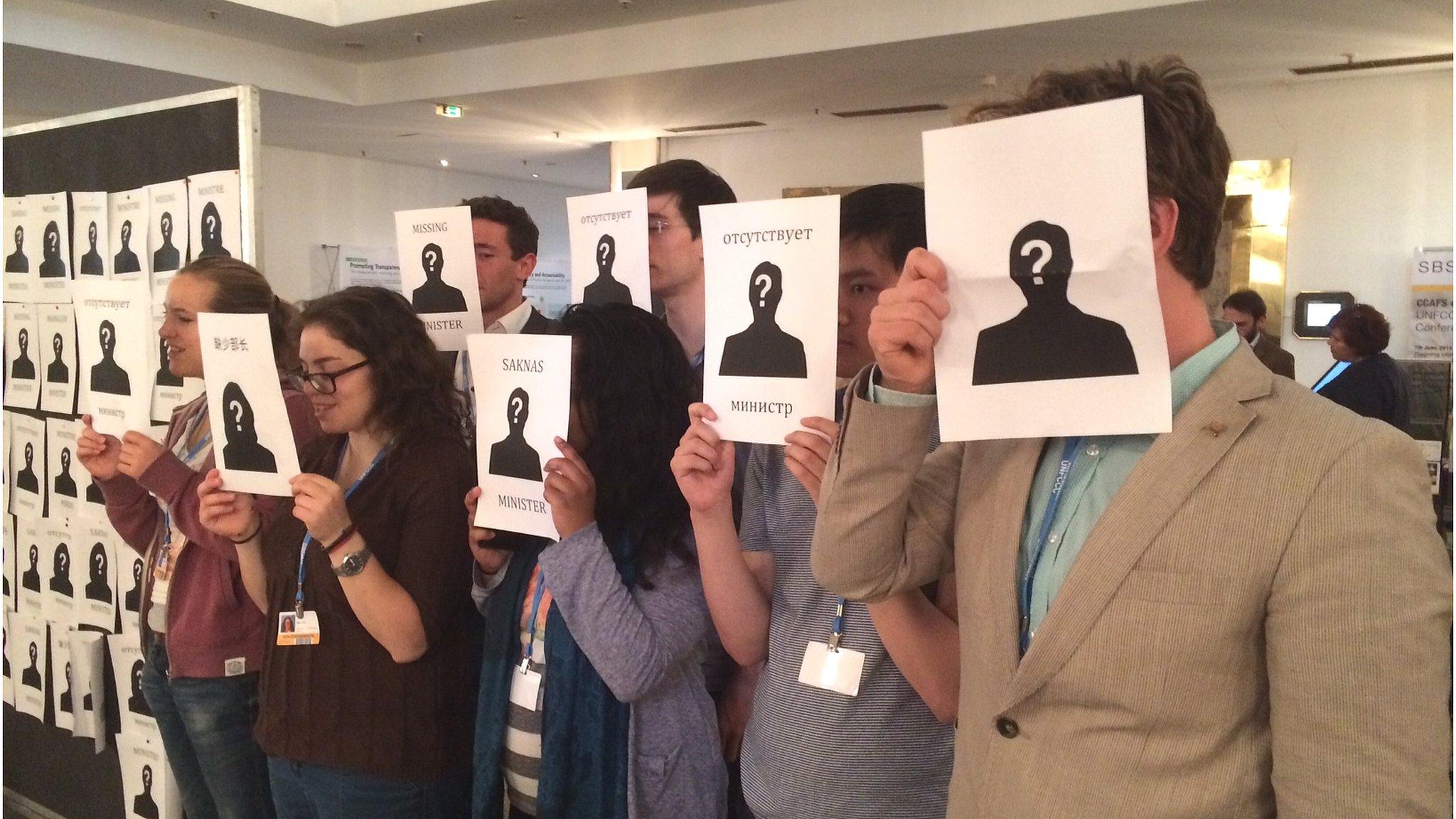

Developing countries will have the final say on the funding of projects

Back in 2009 in Copenhagen, the last time the world believed it was going to seal the deal on climate, cash was also uppermost in many minds.

The richer nations promised to help the poorer ones with a finance package that would amount to $100bn a year, in public and private funds, by 2020.

Show me the money

To get the ball rolling, the wealthier nations said they would give $10bn a year in fast track finance, external between 2010 and 2012.

But there was a great deal of confusion about this money, external with many concerned about the role of the World Bank and how much of it was really distributed as loans.

"It was a lost opportunity to build confidence," says Tosi Mpanu-Mpanu, a senior negotiator from the Democratic Republic of Congo and a rising star in the UN climate talks process.

"Developed countries have assured us that money has been disbursed, while developing countries have no clarity if that money was ever received."

While the recession certainly helped to curb the scale of the monies, external that flowed from rich to poor, there were other factors at play as well.

Strangely the least developed countries, the ones with the greatest need, weren't the ones who got the bulk of the funds, external.

"About two thirds of global aid flows go to middle income countries," said Alex Evans, a senior fellow with the Centre on International Co-operation.

"If you look at the clean development mechanism (a scheme to encourage renewable projects in poorer countries) the main beneficiaries have been China, Brazil and a few other emerging economies."

The impacts of typhoons like Haiyan will be treated as loss and damage issues

"When you look at the average middle income country's GDP today, only 0.3% comes from aid, it's almost a rounding error."

"But when you look at the average least developed country, 10% comes from aid and the same holds true for climate finance. They are much more dependent."

The richer countries have also annoyed the poorer ones by giving the bulk of their money to mitigation projects, rather than helping them adapt.

An Oxfam study in 2012, external found that just over one-fifth of finance went on helping developing nations to build resilience.

Bitter harvest

There are a couple of reasons for this. Grants from richer countries are often used to support loans for projects - and private investors are keener on mitigation projects such as solar parks that have a better chance of returning their investment.

"Building resilience and adaptation are very difficult things to do, they're not as simple as building a wind farm," says Liz Gallagher a long-time participant in global climate negotiations with environmental think-tank , E3G.

"They're about creating things like resilient transport systems that can withstand flooding and gales - This has been under resourced and it has created bitterness within the very poorest countries who haven't been receiving funds."

Despite all the setbacks, there is now a growing sense of optimism about a new development called the Green Climate Fund, external (GCF).

The fund has finally settled the rules for how it will collect and spend money after years of wrangling between the rich and poor.

For building simple flood defences, funding has been hard to come by

Among the key changes that the fund promises are a 50-50 split between adaptation and mitigation projects, and there will be no projects set up in a developing country without the full agreement of that government.

"We want to push for what we call a fit-for-purpose approach," says Tosi Mpanu-Mpanu who, as well as being a negotiator, is also an alternate board member of the GCF.

"A small scale adaptation project in rural Africa would be able to tap into the fund as easily as a large-scale hydroelectric project in South America or Asia."

Despite the low-key progress of the GCF, it still has some significant hurdles to overcome.

Right now it has no cash, although funding commitments are likely to be made in the next few months.

At present, the European Union can't give any money to the fund as accounting rules demand a seat on the board if the EU is to be donor.

And the fund will not be able to help out with scenarios like Typhoon Haiyan, which devastated parts of the Philippines last year. Those sorts of events are likely to come under a new mechanism on loss and damage that is still a major bone of contention, external between rich and poor.

Despite these issues, the GCF is popular among developing countries because it promises that control will remain with the poorer nations and the funds, once they start to flow, should be consistent.

But there is still a long way to go. And if the fund doesn't develop in the way that many expect, it could have ramifications for the entire process, says Tosi Mpanu-Mpanu.

"There is a need for the developing countries to see that there would be certainty in terms of future flows of finance, otherwise we won't see much ownership of this process from many of the parties in Paris.

And no deal without it, I ask?

"I'm not afraid to say so," says Mr Mpanu-Mpanu.

"No money, no fund, no deal in Paris."

Follow Matt on Twitter., external

- Published6 June 2014

- Published7 June 2014

- Published5 June 2014