Malaysian jet MH370: Refined analysis drives new search area

- Published

- comments

Search teams have spent months trying to find signs of the missing plane

As expected, and reported by the BBC last week, the search for MH370 is going to shift hundreds of kilometres to the south of where an Australian defence vessel thought, mistakenly, it had detected signals from the jet’s submerged flight recorders.

The new region is a consequence of further, refined analysis of the brief, automated satellite communications with the plane in its last hours.

This search area focuses on the so-called “7th arc” – a line through which the analysis suggests the jet had to have crossed as it made a final connection with ground systems.

The interpretation of the data is that this last electronic “handshake” was prompted by a power interruption on board MH370 as its fuel ran down to exhaustion and its engines “flamed out”.

The final connection is the jet trying to log back into the satellite network after the interruption, made possible perhaps by an auxiliary power source firing up. But there are very strong indications that MH370 crashed soon after. And here’s why.

'Spiralling downwards'

Examination of the data shows there was another interruption and logon request from the plane much earlier in the flight. Such interruptions can occur for a number of reasons, including software glitches. But the sequence that follows a logon is telling.

About 90 seconds after the satellite link is re-established, the entertainment system onboard the plane should also try to reconnect with the ground network. All this can be seen in the data for a handshake that occurs at 18:25 GMT, three minutes after the last radar sighting of the jet.

But this entertainment reconnection does not occur following the 7th arc handshake at 00:19 GMT, almost five hours later. The hypothesis then is that MH370 cannot make such a request because by that stage it is spiralling rapidly downwards or has already even hit the water.

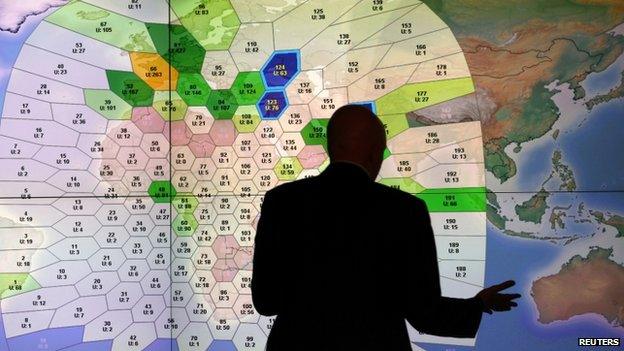

Satellite system operator Inmarsat has been calculating where the plane is likely to have ended its journey

This all means the wreckage should be very close to the 7th arc. But where precisely is dependent on a number of variables that include such aspects as the plane’s performance on that day and even the wind conditions.

A model has been produced that takes account of all these features, and several teams within the investigation have been running the numbers; this is not the sole work of the satellite system’s operator, Inmarsat.

What is more, these teams have run the numbers independently of each other. However, the collected view has arrived at a zone of highest priority covering some 60,000 sq km (23,200 sq miles).

It is a strip running for about 650km (400 miles) with a width of 93km. Its northern end is a good 800km from where the ADV Ocean Shield’s towed pinger locator device detected those possible pulses from submerged flight recorders.

The Fugro Equator vessel is mapping the sea bed of the new search area

These detections, it turns out, were not what one would have expected from properly functioning beacons, but only damaged ones. Nonetheless, it was determined that an underwater search using an autonomous sub should take place. As we all know now, it was fruitless, and the location has been ruled out as a final resting place for MH370.

Two ships – the Chinese survey vessel Zhu Kezhen and the Australian-contracted Fugro Equator - are now busy mapping the ocean floor in the new search area.

Once they have a detailed map of the shape and depth of the sea bed, the investigation team can then summon the best – and also the most appropriate - submersibles in the world to go hunt for sunken wreckage.

The Australian authorities have laid out much of the analysis, and their reasons to go with the new search area, in a 55-page report, external.

While no-one yet can presume they know what happened on MH370, it is clear from reading this document that investigators are working on the idea that the crew was unconscious for the larger part of the flight. Everything we know about MH370, and everything we've learned from previous accidents, would seem to point to the jet ending its flight after having spent a long time on autopilot.

But quite how it could have got into this situation, eventually crashing into the southern Indian Ocean, is for now pure speculation.