Animal procedures show small rise

- Published

.jpg)

Mice make up three-quarters of the animals used in science experiments

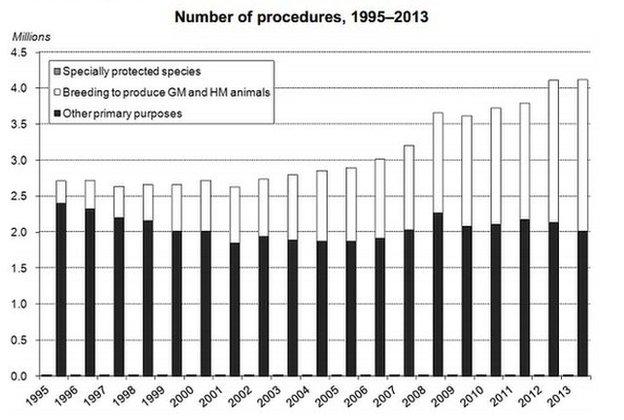

The number of experimental procedures involving animals in Britain showed a small rise last year, despite a pledge by the government to reduce them.

Figures show 4.12 million procedures were carried out with animals, a rise of 0.3% on the previous year.

Animal welfare campaigners said the government had "broken its promise" to cut the number of tests.

The Home Office statistics show more than half of the procedures entail breeding genetically modified animals.

Overall there was a 6% increase in breeding GM animals and a 5% decrease in other procedures.

There were 3.08 million procedures on mice (75% of the total), 507,373 using fish (12%) and 226,265 with rats (6%). The remaining 5% includes birds, guinea pigs, dogs, cats, horses, sheep and cattle.

In 2010, the coalition government pledged to promote higher standards of animal welfare.

They stated: "We will end the testing of household products on animals and work to reduce the use of animals in scientific research."

Michelle Thew, chief executive of campaign group the British Union for the Abolition of Vivisection, said: "The government has now failed for a third year on its 2010 post-election pledge to work to reduce the number of animals used in research.

"As a result, millions of animals continue to suffer and die in our laboratories."

But Wendy Jarrett, chief executive of Understanding Animal Research, which works to promote understanding of biomedical research involving animals, said, "It's not correct to say that the number of animals used has increased."

"Although the number of procedures, including breeding, has risen slightly, the number of animals used has been reduced by over 15,000 (0.4%)," she told BBC News. "This is slightly confusing, but the difference arises because there are particular cases when animals are the subject of more than one procedure each."

Questionable commitment

Prof Roger Morris of King's College London highlighted that excluding the breeding of GM animals, 2013 in fact saw a 5% reduction in "what we scientists would call an experiment".

The accompanying rise in breeding numbers, Prof Morris said, demonstrates the contribution of modern genetic techniques. "We're modelling more complex diseases more accurately than before."

Other animal welfare groups claim that animal research is outdated. The Humane Society International stated the new figures represent a "crisis for medical research". Its director of research Troy Seidle said, "Much of [British] research is dominated by animal models of human disease that simply don't work, and that has to change if we want better quality medicine."

However, scientists like Prof Robin Lovell-Badge, from the MRC's National institute for Medical Research, argue that despite significant advances in areas such as stem cell research, animal experiments remain essential. "We need to understand how these stem cells respond to physiological signals within the body," he said.

The rise in the total number of procedures was 0.03% between 2012 and 2013

"Don't be misled by thinking that everything's going to be done in the tissue culture lab - that's not true."

In fact, some researchers question the wisdom of the coalition's 2010 commitment, external to reducing animal experiments.

"I think it's unfortunate that they are so committed to it," Prof Morris said, "because the vital thing is to ensure the wellbeing of the animals and the value of the research.

"If, as a result of big data analysis... as new opportunities come up and we get new insights into disease, if we then have to queue up, say, because [the number of animals] must be decreasing, that's very unfortunate because you're actually slowing down research which will make a big difference.

"On the other hand, it is true that getting everyone to think very hard about it is valuable."

Citing changes and reductions made by some pharmaceutical companies, Prof Morris added, "British standards are providing a point of best practice for the rest of the world."

This contrasts with the view of campaign organisations like the National Anti-Vivisection Society, which condemned the rise in procedures as "a national disgrace". The society's president Jan Creamer said, "We are deeply concerned that genetic modification of animals is being allowed to simply increase year on year."

The 6% increase seen in 2013 makes it the first year in which over 2 million procedures were undertaken to breed GM animals.

Basic research

Prof Dominic Wells, from the Royal Veterinary College, defended the importance of this type of work: "Genetically altered mice play a vital role in understanding gene function and the role of such genes in disease." Such animals are crucial, Prof Wells said, for developing models of disease, "especially the 5000 or more rare genetic diseases, which add up to more than 5% of the human population."

Of the total 4.12 million procedures started in Britain last year, nearly half (49%) took place in universities, with commercial organisations accounting for 26%. Government departments, NHS hospitals and other public bodies together housed 16% of animal procedures.

Broken down by the purpose of each procedure, 51% were breeding, 28% were classed as "fundamental biological research" and 13% "applied studies" for human medicine or dentistry.

The fact that more than twice as many animals were used in basic research, compared with more medically applied work, does not surprise senior scientists.

"The ground base of fundamental research has to be massive," said Prof Paul Bolam, a neuroscientist from Oxford University. "Without all that, the breakthroughs wouldn't come.

"All these advances in techniques enable us to ask questions that we couldn't even have imagined 20, 10, or even five years ago."

Modern treatments for Parkinsons's disease, among countless others, Prof Bolam said would "never have been developed" without basic research carried out in animals.

- Published7 February 2014

- Published14 May 2014

.jpg)

- Published16 July 2013

.jpg)