Pushing frontiers of deep sea exploration

- Published

Amphipods are the most abundant of free-swimming creatures in the deepest depths

Marine scientists are delighted with the latest video footage of life and death from the deepest, most mysterious region of the ocean.

One has described it as the best they have yet collected.

A deep sea probe shot the videos in April and May during an expedition that plumbed the 10,000m depths of the Kermadec Trench, northeast of New Zealand.

The images reveal the hunting strategy of a large enigmatic fish, the swimming style of a gigantic deep sea crustacean and new information on the activities of the world's deepest living fish.

These are new insights on the behaviour of marine animals which inhabit one of the most extreme and inhospitable realms of the planet - the ocean depth range between 6,000m to 11,000m where the floor of the abyss plunges into great troughs, known as ocean trenches.

Oceanographers call it the hadal zone. At its lowest point, the pressure reaches one tonne per square centimetre and the temperature drops to one degree C.

The technical challenges to sending manned and unmanned submersibles into this environment mean that a sizeable portion of the planet's sea floor remains terra incognito.

According to Andy Bowen, chief engineer at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) in the US: "The hadal zone… represents an area somewhat equivalent to that of North America. So it's a substantial area of the ocean that is essentially unexplored."

Marine biologist Alan Jamieson of the University of Aberdeen in Scotland regards this as an unacceptable gap in our knowledge of the ocean ecosystem.

"The hadal zone is 45% of the ocean's depth range. So the entire discipline of deep sea biology has concentrated on the shallowest 50% and that seems wrong," he said.

Jamieson led the team which collected the latest video material. He talks about the expedition and its discoveries in the science radio series Into the Abyss on BBC Radio 4.

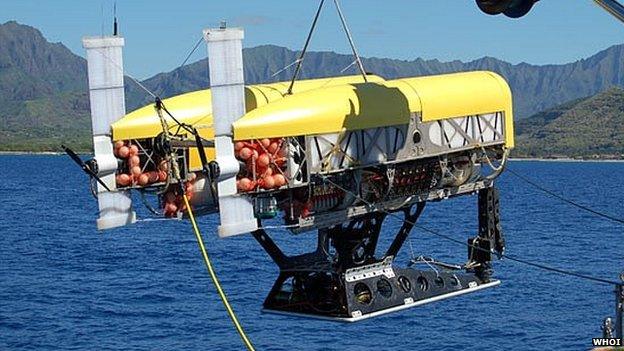

His spectacular images are some consolation for a technical disaster during the scientific voyage: The catastrophic implosion at 10km depth of the US$3.1m submersible robot, Nereus.

Nereus was the world's most advanced deep sea research vehicle - designed and built at Woods Hole. Nereus was lost during only its second mission in the hadal zone.

The flagship Nereus underwater vehicle was destroyed recently in the Kermadec trench

The expedition was the first to attempt to study systematically an ocean trench at the different depths across its entire width. It was the inaugural mission of an international research programme called Hades - Hadal Ecosystem Studies. The scope of that project is much reduced with the destruction of Nereus at the bottom of the Kermadec Trench.

Trenches exist where tectonic plates of ocean crust collide. One great raft of crust is slowly descending into the Earth's interior beneath the edge of the other plate.

At the surface, the junction between them is the trench - a broadly V-shaped feature which can run thousands of kilometres in length. The deepest is the Mariana Trench with a floor as deep as 11,000 metres at one location.

The Hollywood film maker Cameron visited its lowest point, Challenger Deep, in 2012. Cameron's submarine mission cost millions of dollars and he reported seeing little in the way of interesting creatures. Alan Jamieson's new video images came at much cheaper price.

The videos were captured during several deployments of a device called a hadal lander. A lander is relatively simple piece of hardware: lights and cameras within a pressure-resistant housing. It also carries a pole on which a dead fish is secured. The bait lures hadal creatures into the camera's field of view, once the whole contraption has been dropped to the sea floor.

In the recent Kermadec expedition, the Aberdeen team began their deployments in the relative shallows.

At 1,554m depth, the lander and its mackerel lure pulled in a mass of squirming eels of two species: large arrow tooth eels and smaller snubnose eels.

The video camera caught the last few seconds of existence for a snubnose eel. In the frenzy of scavenging, a large arrow tooth grabbed the smaller species and carried it off, undulating backwards, into the darkness. "That was a direct kill," said Alan Jamieson.

Even at 1,500 metres, food parcels like the one delivered by the lander are few and far between. Fish detect its odour and emerge from the enveloping darkness to converge on the feast. All species in this environment will scavenge but the new footage creepily shows that a feeding frenzy is also an opportunity for predation.

Another revelation about deep sea hunting behaviour came with a deployment to the upper slopes of the trench itself at 5100 metres. Eel-like fish called cusk eels are frequently spotted at this depth, and deeper. The deep dwelling cusk eels, Bassozetus sp, grow up to one metre in length.

Alan Jamieson said that on previous expeditions, he often saw cusk eels come to the bait but he never saw them do anything interesting. This time the lander caught several occasions when they burst into action in what Jamieson described as some of the best video sequences he's ever taken. The fish's glum-looking, tight-lipped face opens up to form a submarine vacuum cleaner.

Deep dwelling cusk eels grow up to 1m in length

The cusk eel holds its position at the bait and waits for the odour of dead fish to attract crustaceans called amphipods. Amphipods are the most abundant of free-swimming creatures in the deepest depths. Dr Jamieson theorises that cusk eels only spring into action when amphipods large enough to bother with swims close. When the fish somehow detects their proximity, its mouth springs wide open in a split second, sucking up the amphipod in a rush of water.

Deeper in the trench, there is an amphipod species which has nothing to fear from fish. This creature is unofficially known as the Supergiant - its scientific name is Alicella gigantea. The Kermadec expedition this year captured the first footage of the Supergiant swimming. On this occasion, the animal was caught, brazenly ploughing through a shoal of pink snailfish at 7,243 metres below the surface.

Most members of the amphipod group are small, typified by the species many of us are likely to have encountered: the sand hoppers which ping out of disturbed seaweed on the beach.

The adult Supergiant is colossal compared to any other amphipod species. On previous expeditions in the Kermadec and Japan trenches, individuals brought up in deep sea traps have measured as long as 28 centimetres, almost one foot.

Marine biologists speculate that Supergiants evolved gigantic size as a defence against predation. At some point in the past, their ancestors had the luck to develop mutations in genes which regulate growth.

Another adaptation to this environment are food stores in their bodies, according to marine biologist Ashley Rowden at New Zealand's National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research. He said that Supergiants which have been brought to the surface feel as though they are made of wax.

"The belief is that the waxy materials are a food storage source for times when there isn't food for those Supergiants to exist on. They are able to use what they've stored from a previous big feast."

Sharing the Middle Trench depth range with the Super Giants are the snailfish - the deepest living fish known. They have the appearance of large tadpoles made of pink jelly. They are semi-transparent. The lights of the hadal camera illuminate orange blobs within their bodies. These blobs are their livers.

Snailfish feed on small amphipods. The greatest depth at which they have been seen is 7,700 metres. The fish (Notoliparis kermadecensis) in the Kermadec Trench look more or less identical to those seen in the Japan Trench way to the north. However genetic analyses show they are different species and not that closely related to one another. They are closer cousins of the shallower water snailfish species in their respective parts of the world.

On this and previous expeditions, snailfish have been brought to the surface in traps. According to Ashley Rowden, the jelly-like consistency makes a snailfish hard to handle. "It's like handling a water-filled condom. It slips around in your hand and you're not quite sure which bit you should be holding so that it doesn't drop to the deck."

The latest footage of snailfish in their natural environment reveals them to be more numerous and more energetic than the scientists had supposed. Alan Jamieson says the snailfish had also appeared to be wedded to the sea floor. The new video reveals them disporting in mid water around a precipitous cliff of volcanic rock. The water depth here was 7,669 metres.

"We always thought that when you get down to those depths, you'd be lucky if you saw one or two, eking out an existence in this really deep water but we've been very, very surprised to see so many being so active," said Alan Jamieson.

"The more I do this the more I don't consider the very deepest parts of the ocean as that different (from the rest of it). They are not weird and 'out there'…. They are just an extension of every other marine environment."

The first part of 'Into the Abyss' was broadcast on Wednesday 16th July at 9 pm and will be repeated on Tuesday 22nd July at 11 am.