Rosetta heads for space 'rubber duck'

- Published

- comments

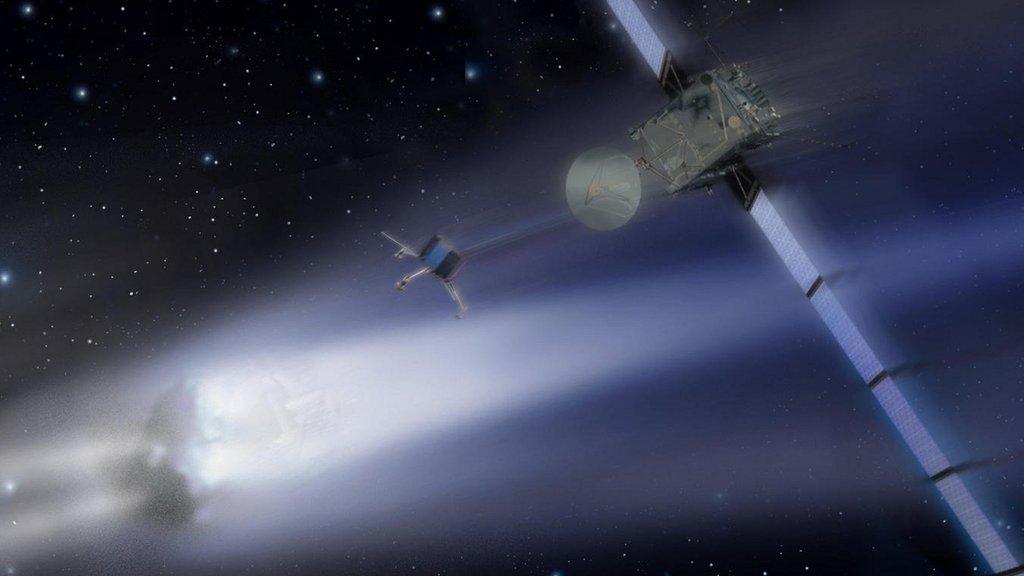

Europe's mission to land on a comet was always going to be difficult, but the pictures released this week of the giant ice ball illustrate just how daunting the task will be.

Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko is far more irregular in shape than anyone imagined.

It has already been dubbed the "rubber duck" in space.

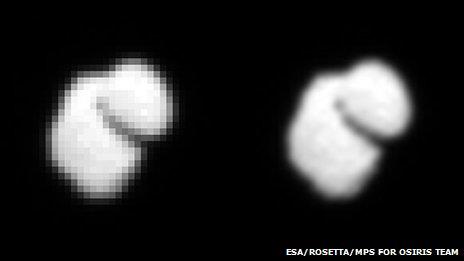

The latest pictures were acquired by the approaching Rosetta probe from a distance of about 12,000km.

Over the course of the next three weeks, the spacecraft expects to reduce that separation to less than 100km.

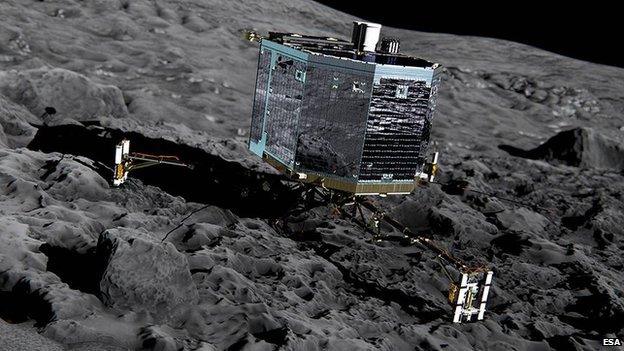

Shortly after, the probe will begin the process of mapping the 4.5km-wide ice object, to find a place to put down the little Philae contact robot in November.

The "movie" on this page comprises 36 individual images taken on Monday. It has been sped up; a full rotation takes 12.4 hours.

The individual pixelated pictures have been interpolated (smoothed) to make the outline of the comet easier to understand. But even from 12,000km, the dramatic duck shape is obvious.

The big distance to the comet means pictures are still highly pixelated (left)

Explanations have been flying around since first word of the irregular form leaked out on Tuesday (more on that issue below).

Is comet 67P a true "contact binary" made up of two distinct objects that are either just touching under gravity or melded together following a low-velocity impact?

If distinct parts, do they originate from the same body, or were they originally part of unrelated objects that only came together at a later date?

Is it possible that what we are looking at is simply a comet that has been sculpted into this funny shape, either through the uneven loss of ice or through impacts with other space objects such as meteoroids?

And how do any of the questions above bear down on the issues of composition and density - issues that will influence strongly how and where Philae tries to make its landing?

Like all good scientists, the European Space Agency's Rosetta team is not rushing to judgement.

"Care and caution is needed; don't jump to conclusions," warns project scientist Dr Matt Taylor.

"We're still too far away at this moment; we're still using interpolated images. So speculate all you want, but we really have to wait until we get there and start doing detailed observations," he told me.

Those who followed the US space agency flyby of 103P/Comet Hartley 2 in 2010 will recall the discussion about the smooth "saddle" in the middle of the peanut-shaped body.

Even now there is debate over whether Hartley 2 is a contact binary, and that with the benefit of pictures taken from a distance of just 700km - a tenth of the separation we're talking about for 67P today.

Nonetheless, when Rosetta's new pictures came in, a wry smile must have spread across the faces of the Esa team-members planning the Philae landing.

Their job was always going to be interesting. It's a lot more interesting now.

Picture policy

Which brings me neatly on to the hoo-hah this week over the release of Rosetta images.

I touched on this subject a couple of weeks ago, but it fairly spectacularly blew up on Tuesday when the first rubber duck images, acquired on Friday 11 July, were posted on the website of the French space agency (Cnes).

"Unauthorised", "unofficial", "unscheduled", "leaked" - use your own term, but this route was not the normal one.

The official release policy has seen a weekly posting to the Esa website at 1300 GMT every Thursday, external.

Whatever reason Cnes had to publish its "preview", the agency later regretted it because the pictures were then taken down. Too late, of course; the BBC and other news outlets had already reposted them.

But the affair opened up once again the question of public access to Rosetta images and whether public interest is being served by the current one-sneak-peek-a-week policy.

On Wednesday, senior figures on the Rosetta mission repeated the reasoning for the limited release, external (you can also read my earlier posting on the topic here).

It essentially boils down to giving mission scientists - the people who've designed and invested time in the instruments - time to trawl the data and make first claim on any discoveries.

Hartley 2 had an interesting shape as well

This is laudable and just on many levels, but is harder and harder to justify in this age when social media demands instant access and wide distribution.

Peruse the special interest websites dedicated to space matters, like raumfahrer.net, external, and you can see how much the world has changed since Rosetta launched in 2004.

The public now expect to see a steady stream of images from the missions they have funded, and the impact this has on engagement is so much greater when this stream does exist.

Esa in the last few days has found itself in the middle of a storm, having to justify the one-sneak-peek-a-week approach. Whether that line can hold, time will tell.

But in truth, this is not really Esa's call; it is the decision of the agency's member states. This is how Esa works.

The remarkable Osiris camera system on Rosetta is principally a German contribution to the mission.

It is the German space agency (DLR) and the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research (the lead scientific institution) that "own" these images.

It is they who have the power to release them more regularly.

Artist's impression of Philae on the surface of Comet 67P

- Published15 July 2014

- Published10 July 2014

- Published3 July 2014

- Published19 June 2014

- Published20 January 2014