Sandstone shapes 'forged by gravity'

- Published

The study offers a new explanation for landmarks like the enormous Rainbow Bridge in Utah

Geologists have discovered the secret that gives dramatic natural sandstone monuments their shape: gravity.

By studying cubes of sand in the lab, they showed that areas squeezed by vertical stress are protected from erosion, while others wash away.

The process had proved difficult to study, because natural slabs of sandstone erode over millions of years.

The key to the experiments, published in Nature Geoscience, external, was an unusual "locked sand" dug from a Czech quarry.

The study's first author, Dr Jiri Bruthans from Charles University in Prague, said the results revealed the "Michelangelo" behind some of the world's most famous rocky landmarks.

"The stress field is the master sculptor - it tells the weather where to pick," he told BBC News.

Erosion by wind and water, it seems, is merely the sharp instrument. The remarkable shapes are controlled by internal stresses and strains within the rock, applied by the pull of gravity.

Accelerated model

As well as showing they could predict the shapes with mathematical models of that stress field, Dr Bruthans and his team sandwiched small cubes of sand under various weights and submerged them in water.

The sides of the cube started to fall away within minutes, leaving fewer and fewer grains of sand to bear the weight. As that process continued, eventually the pressure on the remaining column caused the grains to lock together and resist further erosion.

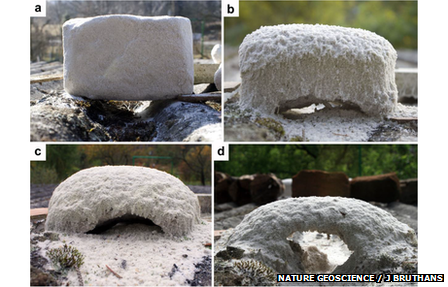

Cubes of sand 10cm high, squeezed under weights and submerged, produced various pillars and arches

When they added faults or other distortions to the cube, and shifted the direction of the pressure applied, the scientists were able to reproduce a gallery of the sort of shapes seen in natural sandstone landforms.

They were only able to watch all this happen because of the strange, sticky quality of the sand they used.

From the Strelec Quarry, in the north of the Czech Republic, the team collected samples of a sand with particular interlocking properties: "Strelec locked sand". It is so soft that for many years it was mined in the quarry using hoses - but when it dried out, explosives had to be used.

For his experiments, Dr Bruthans used 10cm blocks of this locked sand that were dried out an oven.

"It was very clever to find this rock out of a quarry that would behave in an accelerated way, compared to those famous sandstone arches," commented Dr Simon Mudd, a lecturer in landscape dynamics at the University of Edinburgh, UK.

"They've really demonstrated convincingly that as you erode this material, it begins to concentrate stress," he told the BBC.

The famous Delicate Arch - gravity's answer to Michelangelo?

To show that the principle also applies to regular sandstone, Dr Bruthans and his team also took small cubes of normal, "cemented" sandstone from the same quarry and attacked them with cycles of heat, cold and salt, to simulate natural erosion.

Mystery solved

In all cases, Dr Bruthans showed that it was pressure that determined the shapes left behind.

"You can control it completely," he said. "You select the pillar direction, by choosing the points where you apply the compression."

One experiment even showed that a block of the Strelec sand, placed straddling a small gap and left outside in the rain for 15 months, would naturally form an arch.

A brick of sand, left in the rain for over a year, eroded to form an arch

All of these processes can be predicted by modelling the stress field, Dr Bruthans emphasised. "It's just the stress which controls the shape - nothing else."

The results were enough to convince Dr Mudd: "It's a very compelling combination of experimental and numerical work," he said.

In an accompanying comment article, external for Nature Geoscience, Prof Chris Paola from the University of Minnesota, US, described the discovery as "a lovely and elegant formative mechanism for a lovely and elegant kind of landform".

"These natural sculptures have delighted countless visitors, some of whom must have paused to wonder where they come from," Prof Paola wrote. "Here is an answer."

- Published26 January 2014

- Published6 January 2014

- Published29 August 2013