The past, the present, and the challenges ahead for Europe's comet chaser

- Published

After a precisely orchestrated 10-year chase across the solar system, the European Space Agency's Rosetta spacecraft finally caught Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko on 6 August 2014. Since that historic rendezvous, Rosetta had been in a powered orbit around the comet: the first of its kind. The craft was also carrying a separate probe called Philae, destined for the comet's surface. On 12 November, mission controllers confirmed that Philae had detached from its "mothership" and successfully conducted a landing - once again making history.

Rosetta was sent into space on board an Ariane 5G rocket in March 2004

Has Rosetta's target changed?

Rosetta was originally due to launch in 2003 aimed at a different, much smaller comet called 46P/Wirtanen.

However, the failure of an Ariane 5 rocket attempting to put a communications satellite into orbit in 2002 meant that the Rosetta mission was delayed until the fault was found. Instead of the tiny 46P/Wirtanen, the mission was re-focussed on the larger 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko, external.

The thrust of this mission is to catch up with the comet while it is still in the colder regions of space and to put a lander on the icy body as it begins to warm up on its journey in towards the Sun.

How does a spacecraft survive a trip of 6bn km?

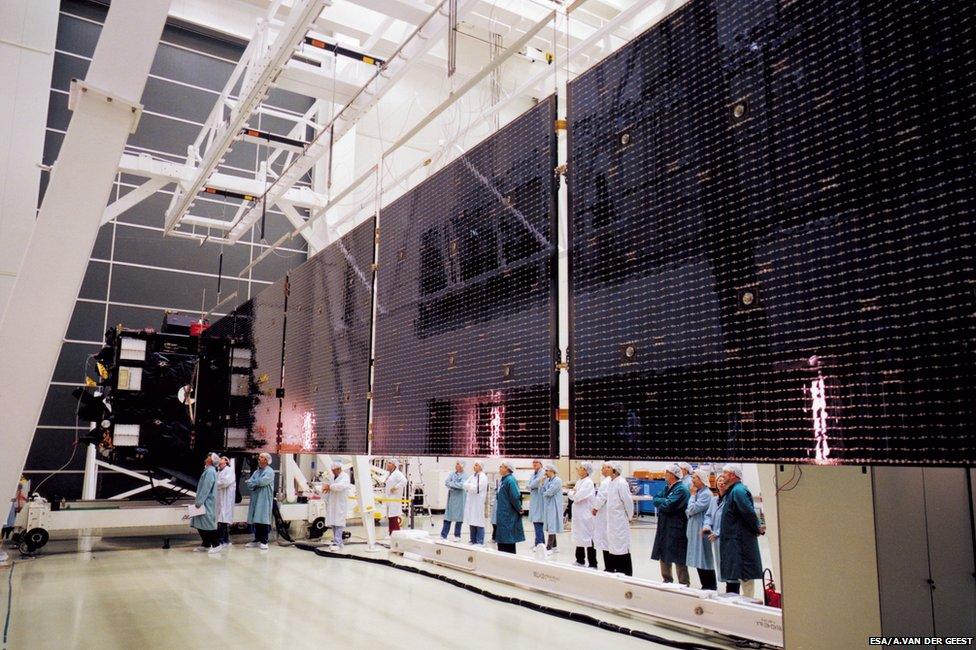

The use of advanced solar-panel technology has been key to making sure the spacecraft is able to power itself throughout this massive journey.

Swinging around the Sun five times, the probe has had to cope with extreme heat and cold, sometimes operating in parts of the Solar System where levels of sunlight are only 4% of what we receive on Earth.

These 14m-long solar panels have kept Rosetta powered up during its 10-year flight

When it has travelled closer to the Sun, Rosetta has been prevented from overheating by special radiators. It has employed multi-layered insulation blankets to fight off the cold.

Controllers also put the probe into a deep hibernation for almost 1,000 days as a way of conserving energy. When Rosetta finally woke up in January this year, the relief on the faces of Esa staff was plain to see.

How did Rosetta catch the comet?

Comet 67P is hurtling through space at a speedy 55,000km/h (over 15km per second).

Rosetta has been gaining on it, over the last decade, through a series of three gravity-assisted swings around the Earth and one around Mars.

To ensure that Rosetta was in the right place at the right time, controllers carried out a series of 10 orbit-correction manoeuvres during June and July, in which the probe's speed was significantly reduced relative to the comet. One of these involved firing the probe's thrusters for almost eight hours.

Rosetta's speed relative to the comet was 2,880km/h, but at the time of orbital insertion it was mere walking pace: around 3km/h.

On 6 August, the final thruster burn took place, putting the probe into a triangular form of powered orbit 100km above the "ice mountain".

What came after the rendezvous?

That was all just the first, tricky step.

After three months in that powered orbit, gradually dropping closer towards the "dirty snowball" and taking photos - including the occasional selfie - history was made again.

On 12 November a tiny lander, called Philae, landed on the surface of the comet after being released from Rosetta. It will now attempt to carry out the most comprehensive set of tests ever performed on the composition of these ancient objects.

Before sending Philae, Rosetta itself carried out an analysis of the comet's surface and lowered itself right into the gravity of 67P, at a separation of about 30km.

A landing site was chosen on 15 September and later christened "Agilkia" following a public competition.

The Philae lander, about the size of fridge and constructed from carbon fibre, was dropped to the rocky surface from about 1km. It was equipped with harpoons to attach itself. Philae is designed to be able to land on a slope of up to 30 degrees. Esa says the feet of the lander have large pads which allow it to touch down on a soft surface, but these feet are also able to place screws into the icy surface.

Delight at the moment Esa controllers realised that Rosetta had woken from a long slumber

If the surface of the area was very soft, the lander's feet may have sunk into it - but any sinking would eventually have been stopped by the bulkiness of the lander's body. In all scenarios, the lander was expected to be able to safely transmit its data.

It will now begin to use a suite of nine instruments, including a special drill, to probe the icy body in unprecedented detail.

What big scientific questions is Rosetta attempting to answer?

The "mothership" Rosetta itself will accompany 67P on its approach to the Sun throughout 2015. It is equipped to carry out a range of scientific examinations of its mysterious quarry.

As the comet gets closer to our star, it will warm up and a stream of dust and water vapour will flow from it. Rosetta will try to find out if there are organic chemicals in the mix, that might have provided the elements necessary to start life on Earth.

In September, Rosetta snapped this "selfie" of its solar panels and the comet 67P

Rosetta will also try to answer some slightly less profound questions about the origins of comet 67P, and its distinctive rubber duck shape.

Scientists hope that Rosetta will discover if it is, in fact, two comets that came together in a collision.

Now that the Philae lander has touched down successfully it will also attempt to analyse the ice on the surface. If it has the same atomic composition as the water that fills Earth's oceans, it will strengthen the view that comets delivered the liquid to our planet.