Exotic grains from cosmos identified

- Published

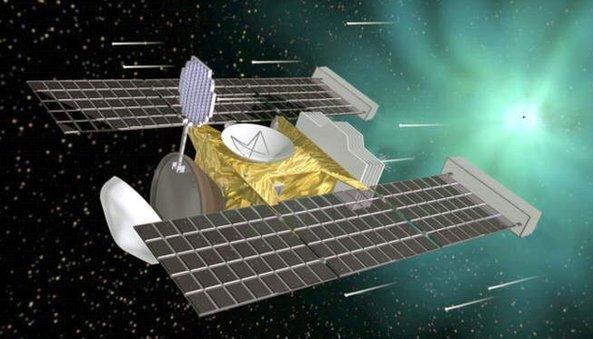

The cosmic particles were stored safely in a capsule that Stardust delivered to Earth in 2006

Scientists may have identified the first known dust particles from outside our Solar System, in samples returned to Earth by a Nasa space mission.

A team of scientists, with the help of more than 30,000 worldwide citizens, has identified seven exotic grains.

The material was captured by the Stardust spacecraft and brought back to Earth in 2006.

The region between stars - interstellar space - is not entirely empty, but is filled with microscopic particles.

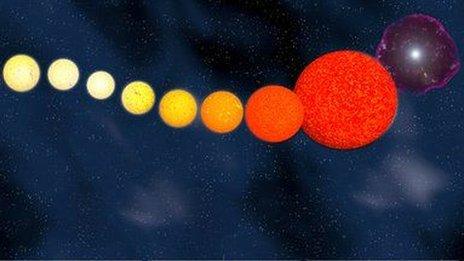

The material that forms interstellar dust is a product of the aeons of stellar birth, evolution and death that went into building our cosmic neighbourhood.

These molecules originated in the extremely hot interior of other stars and were expelled into interstellar space where they condensed into tiny rocks as they cooled down.

Having these particles on Earth means that scientists can characterise them in unprecedented detail. The composition and structure of the collected samples could help explain the origin and evolution of dust in space.

The collected samples could help explain the origin and evolution of interstellar dust

Dr Andrew Westphal, from the Space Sciences Laboratory at the University of California, Berkeley, told BBC News: "Our results are giving us the first glimpse of the complexity and diversity of interstellar dust particles."

A preliminary analysis by Dr Westphal and colleagues, published in Science, external, showed that the seven interstellar candidates are much more diverse in size, chemical composition and structure than anyone had pictured before based on previous astronomical observations and theories.

"It could easily have been that our answer when we did this project was to find that all interstellar dust particles are similar, and we are not finding that at all. They are all different from each other."

Comet dust is older. The material out of which our Solar System formed was heated, melted, mixed and transformed as the Sun and the planets began to take shape. The comets represent the relics of this process and are therefore representative of the composition of our early planetary system.

Stardust was two missions in one. Although it is mostly known for its close encounter with Comet Wild 2, the spacecraft also captured dust flowing in the interstellar dust stream. This stream carries particles made by stars in different parts of our galaxy.

Stardust captured dust particles using a retractable grid of aerogel

Stardust was equipped with a device called the Interstellar Dust Collector, a tennis-racket sized mosaic of 132 tiles made of the lightest manmade solid, referred to as aerogel. This is a silicon-based material that is more than 99% empty space.

The dust particles can travel at hypervelocity, more than 5km per second. Like a net, this light, fluffy aerogel captured dust particles without vaporising them by slowing them down gradually.

More than 30,000 volunteers who signed up to the Stardust@home project, external examined millions of images of the aerogel in search of the carrot-shaped trails left by the incoming hypervelocity particles, which are about two millionths of a metre in diameter.

But not all of the particles embedded in the aerogel are of interstellar origin. The researchers determined that all but three of the tracks were caused by tiny bits of the spacecraft.

Four more possible interstellar particles, as tiny as 0.4 millionths of a metre, were found encrusted in minute craters in the aluminium foil around the aerogel tiles.

The seven dust particles are composed of different silicates - minerals consisting of silica, oxygen and metals - which indicate that each particle may have its own history.

"[The particles] may have formed in one star and were then processed over tens of millions of years in the interstellar medium and mixed in with particles coming from other stars or even particles that formed in the interstellar medium in cold molecular clouds; so it's probably a mixture of lots of different things," explained Dr Westphal.

The dust particles leave a cone-shaped trail as they are slowly decelerated by the aerogel

Ongoing work

Dr Westphal and his colleagues plan further tests to the published results.

The final proof lies in the levels of different chemical oxygen forms, known as isotopes, within them. A different concentration than that found in our Solar System would indicate their extra-solar origin.

It will require several years of hard work to refine the techniques available to measure the abundance of oxygen isotopes in the dust particles without destroying them.

Dr Westphal added: "It's a necessary step before we dare to do anything with the real thing. The problem is that they are just so rare… we cannot dare to take any chances."

More data remain to be analysed. Half of the aerogel tiles and an even larger fraction of the foils will be scrutinised in the next two to three years.

In the meantime, Dr Westphal said the team members were "having fun".

- Published11 April 2012