Neanderthal 'artwork' found in Gibraltar cave

- Published

An engraving found at a cave in Gibraltar may be the most compelling evidence yet for Neanderthal art.

The pattern, which bears a passing resemblance to the grid for a game of noughts and crosses, was inscribed on a rock at the back of Gorham's Cave.

Mounting evidence suggests Neanderthals were not the brutes they were characterised as decades ago.

But art, a high expression of abstract thought, was long considered to be the exclusive preserve of our own species.

The scattered candidates for artistic expression by Neanderthals have not met with universal acceptance.

However, the geometric pattern identified in Gibraltar, on the southern tip of Europe, was uncovered beneath undisturbed sediments that have also yielded Neanderthal tools.

Details of the discovery by an international team of researchers has been published in the journal PNAS, external.

There is now ample evidence that Neanderthal intellectual abilities may have been underestimated. Recent finds suggest they intentionally buried their dead, external, adorned themselves with feathers, external, painted their bodies with black, external and red, external pigments, and consumed a more varied diet, external than had previously been supposed.

One of the study's authors, Prof Clive Finlayson, director of the Gibraltar Museum, said the latest find "brings the Neanderthals closer to us, yet again".

.jpg)

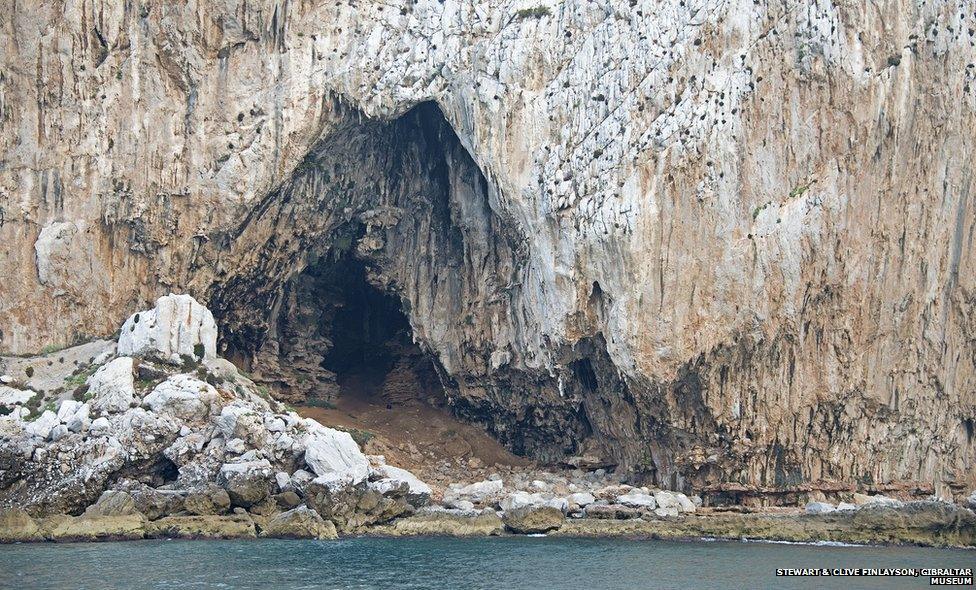

Gorham's Cave is located on the south-east face of Gibraltar

Today, the sea is a short distance away, but when the cave was first inhabited, the shore was several kilometres away

Previous candidates for Neanderthal cave art exist, including motifs from caves in northern, external and southern, external Spain. Possible jewellery, external has been found at a site in central France, and there are even claims Neanderthals were responsible for an early musical instrument, external - a bone "flute" found at Divje Babe in Slovenia.

These proposed flickerings of abstract thought among our ancient relatives have all proven controversial, external. But the authors of the PNAS study went to great lengths to demonstrate the intentional nature of the Gorham's Cave design.

In order to understand how the markings were made, experimental grooves were made using different tools and cutting actions on blocks of dolomite rock similar to the one at Gorham's cave.

The method that best matched the engraving was one in which a pointed tool or cutting edge was carefully and repeatedly inserted into an existing groove and passed along in the same direction. This, the authors argue, would appear to rule out an accidental origin for the design, such as cutting meat or fur on top of the rock.

'Compelling evidence' for Neanderthal art has been found in cave in Gibraltar

Francesco d'Errico is director of research at the French Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS) in Bordeaux, and oversaw these experiments.

"[Dolomite] is a very hard rock, so it requires a lot of effort to produce the lines," he told BBC News.

The archaeologist estimates that the full engraving would have required 200-300 strokes with a stone cutting tool, taking at least an hour to create.

"If you did it in a single session, you would most probably injure your hand, unless you cover your tool with a piece of skin," he said.

Prof d'Errico explained that the rock was in a very visible location in the cave and that the engraving would have stood out to any visitors.

"It does not necessarily mean that it is symbolic - in the sense that it represents something else - but it was done on purpose," he said.

Clive Finlayson said team members deliberately avoided speculation in their scientific paper as they wanted it to be a "watertight" description of the discovery. But, he explained: "One intriguing aspect is that the engraving is at the point in the cave where the cave's orientation changes by 90 degrees.

Team members Prof Joaquin Rodriguez Vidal (L) and Francisco Giles Pacheco (R) inspect the engraving

The geometric pattern was discovered during excavation work by an international team in July 2012

"It's almost like Clapham Junction, like it's showing an intersection. I'm speculating, but it does make you wonder whether it has something to do with mapping, or saying: 'This is where you are'."

Prof d'Errico added: "It's in a fixed location so, for example, it could be something to indicate to other Neanderthals visiting the cave that somebody was already using it, or that there was a group that owned that cave."

The researchers also carried out an analysis of the likely position of the person when they were making the engraving, and whether it was likely to have been made by a left- or right-hander, but they have decided not to publish these results for the time being.

The engraving was first spotted in July 2012 by Francisco Giles Pacheco, an eagle-eyed team member who is director of the Archaeological Museum of El Puerto Santa Maria, Spain.

Sediments covering the engraving have previously yielded stone tools made in the Mousterian style, which is considered diagnostic of Neanderthals. However, other researchers note that such artefacts turn up in North Africa, where there is no trace of habitation by Neanderthals. They have previously reasoned that if Homo sapiens made the Mousterian tools in Africa, they might also be responsible for the ones in Gibraltar.

Some 28km of sea separates Gibraltar from the coast of North Africa, and if you look south from the Rock on a clear day, it's hard to miss Jebel Musa - part of Morocco's Rif mountains - rising above the horizon. However, Prof Finlayson says there is no evidence that modern humans made the crossing until much later. In addition, he points out, Mousterian tools are associated with Neanderthal skeletal remains at the Devil's Tower site in Gibraltar.

Another possibility is that Neanderthals were imitating the behaviour of modern humans they'd come into contact with. While Homo sapiens was in Europe by around 45,000 years ago, Prof Finlayson says the moderns reached southern Iberia later than some other regions, casting doubt on the copycat idea.

But Dr Matt Pope, a Palaeolithic archaeologist at University College London, who was not involved with the latest study, was less convinced.

"The engravings do appear intentional and it's hard to easily envisage a purely functional explanation for them. Consequently it's useful to consider these structured scratches as deriving from abstract or symbolic thought," he told BBC News.

"But linking them directly to Neanderthal populations, or proving Neanderthals made them without any contact with modern humans is harder. The dates presented here are indirect, referring to material from within sediments covering the engravings and not the marks themselves.

"Given the dates also span a period when we know modern humans have reached Europe, a period where we have unresolved 'transitional' archaeological evidence difficult to attribute to either population, I'd be cautious in accepting Neanderthal authorship."

He added: "Certainly, the Gibraltar team have provided another piece of compelling, important evidence which will help bring this period into sharper focus and under deeper scrutiny."

Follow Paul on Twitter, external.