'Pocket' diagnosis for Parkinson’s

- Published

Smartphone technology revealed at the British Science Festival could help diagnose and treat Parkinson's disease.

Symptoms of Parkinson's are currently difficult to measure objectively after the patient leaves the doctor's clinic.

New smartphone software developed at Aston University will bring the doctor into the patient's pocket to assess their movements and speech at home.

Trials are now recruiting online, seeking people with and without the disease.

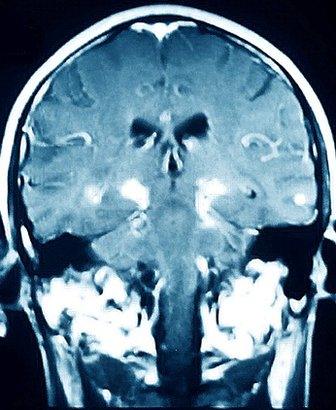

Parkinson's is one of the commonest neurodegenerative diseases, affecting around 127,000 people in the UK.

Diagnosis is based on symptoms including tremor, stiffness and difficulty with movements and speech. However, studies have shown that up to 20% of people diagnosed with Parkinson's show no evidence of the disease in post-mortem examinations.

"Most people who have the disease will never be objectively measured," explained Dr Max Little, a mathematical researcher with Aston's Nonlinearity and Complexity Research Group.

Dr Little's team has developed software that uses the microphone and motion detector of a standard smartphone to provide data to supplement traditional clinical assessment.

Machine learning

Voice change can be an early indicator of Parkinson's. Patients or their family may notice their voice becoming quieter, drifting in pitch and showing vocal tremors.

Over the past eight years, Dr Little and colleagues have been developing tools to capture and quantify these changes in the lab and in the home. Using machine learning they are now able to "very accurately separate those who have Parkinson's from those who don't" - with up to 99% agreement with the diagnosis made by the neurologist in clinic.

Their most recent study, the Parkinson's Voice Initiative, included 17,000 participants providing voice samples via telephone.

Parkinson's is one of the commonest neurodegenerative diseases

Smartphones use accelerometers to measure force in three dimensions. These sensors can be used to collect data on Parkinson's with the phone stowed in the pocket - detecting "freezing of gait" when walking and other characteristic signs of the disease.

By integrating this with GPS and other smartphone data, Dr Little's software can perform complex analyses of behaviours including "how many phone calls you make, what's your socialisation behaviour, are you spending a lot of time outside of the house, are you predominantly sitting or walking, how much do you explore your environment" - all of which can contribute to a diagnostic algorithm for Parkinson's.

Personal diagnostic software raises new issues for diseases like Parkinson's which currently lack disease-modifying treatments.

"For the first time, we could do population screening for Parkinson's," explained Dr Michele Hu, consultant neurologist at the Oxford Parkinson's Disease Centre.

"But preclinical testing is a massive ethical can of worms - the issues must be carefully pre-empted and thought out. We don't know yet how accurate this could be as a predictor and the only way we will know is by very carefully following at-risk individuals over time."

"The ethics clearly has to be worked out - what are we going to use these tools for? What would you like to know? What would you not like to know?" asked Dr Little. "We have made this tool and it's up to the community to decide what to do with it."

Ongoing trials

"Our Western population is aging and 2-3% of people over the age of 75 will develop Parkinson's," explained Dr Hu. "Our aim is to provide a biomarker to diagnose Parkinson's prospectively by focusing on individuals with high risk for the disease."

People at risk include those with a genetic susceptibility to the disease and those with REM sleep behaviour disorder, in which the sleeping individual makes complex and often violent movements during dream sleep.

In a study led by Dr Hu using the new software, subjects are continuously monitored by smartphone for one week, then followed up every 18 months. "It's a much better way of assessing overall disease - a better measure of progression and response to treatment," added Dr Hu.

Dr Little is also seeking 2,500 people with or without Parkinson's to participate in a study, external with the University of Rochester Medical Center in New York. Participants download an app to their smartphone and complete a range of active and passive tests of voice, gait and dexterity.

No two patients experience Parkinson's in the same way. Consequently, in future Dr Little is interested in developing a tool "that could potentially provide specific feedback to people on symptoms that matter to them". Smartphone applications could play an important role in empowering patients to make treatment decisions based on quantitative data they collect for themselves.

But we can't throw the doctor out yet. So far the software has only been shown to discriminate between Parkinson's and healthy controls - the neurologist has a trickier job identifying Parkinson's in a clinical population. "If we wanted to make this into a tool that would do differential diagnosis we would have to test it in that environment," conceded Dr Little.

Dr Little is planning to extend the technology to other disorders including Friedrich's ataxia in children. Smart watches may advance the applications of such software even further.

Dr Anette Schrag is a reader in clinical neurology at the Institute of Neurology, University College London. "This is a very interesting technique that might prove extremely useful in identifying individuals with Parkinson's disease," she commented.

"The diagnostic value of this technique now needs to be replicated and shown not only in those with well-established Parkinson's disease but also in those where the diagnosis is not clear or has just been established."

- Published13 August 2014

- Published16 August 2014