Sports concussion 'breathalyser' proposed

- Published

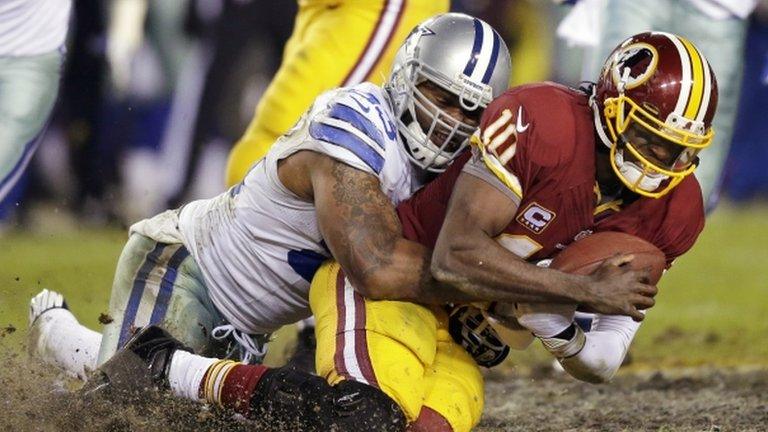

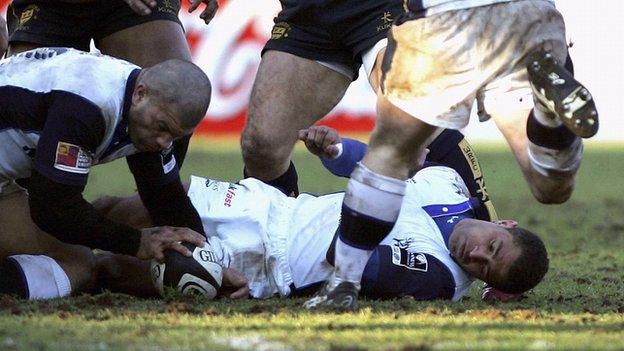

The dangers posed by concussion are currently the subject of considerable scrutiny in several sports

Experts who want tighter regulation of concussion in sport are trialling new medical tests that could provide rapid, pitchside diagnosis.

The "return to play decision" after a head injury is a serious problem that has caused tragedy and controversy.

Among the new proposals is a breath test, which successfully detects key chemicals in early laboratory trials.

Produced by the damaged brain, these chemicals are known to indicate a brain injury when found in the bloodstream.

Further trials will establish whether the same markers can also be detected in athletes' breath, and whether such a breath test would pick up the kind of brain injuries commonly seen in sports like rugby, football and American football.

"These biochemical compounds from the brain can be measured in a number of different fluids - for example, saliva and breath," explained Prof Tony Belli, a neurosurgeon and medical researcher from the University of Birmingham.

"At the moment a breathalyser is tuned to detect alcohol - but you can reengineer it to detect other things. And you need to refine the technology at the same time, to detect very small amounts."

If breathalysers could be adapted in this way, Prof Belli said that the tell-tale chemical signature of concussion could potentially be detected within five or 10 minutes of the injury.

Prof Belli and his colleague Dr Michael Grey presented their work at the British Science Festival, external in Birmingham.

Objectivity called for

Currently, different sports use a variety of psychological tests and waiting periods before making a decision to send a player back onto the field.

The reliability of these tests is controversial and it has been suggested that players can fudge them or even "sandbag" the results, by deliberately underperforming in the pre-game tests that are used for comparison.

Among the tests is a five-minute assessment introduced by the International Rugby Board in 2012, which attracted criticism.

Can heading the ball cause brain trauma in footballers?

Former Ireland full-back and rugby medical adviser Dr Barry O'Driscoll was also speaking on the subject at the British Science Festival. He said: "This was basically the reason I resigned from the International Rugby Board. I'm afraid that five-minute test was unscientific - it didn't prove anything, really."

The Birmingham researchers want to bring more science to bear on the situation. They are also anxious to raise awareness of "second concussion syndrome", which they say is not as widely understood in the UK as it is in North America.

Football controversies

This syndrome was responsible for the untimely death of Northern Ireland schoolboy Benjamin Robinson in 2011, after he received multiple heavy blows during a rugby game.

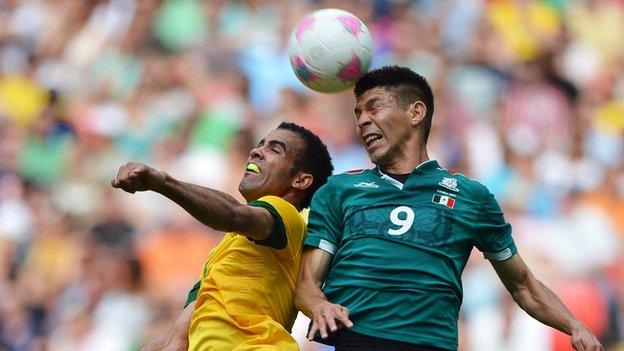

Proposals for a three-minute stoppage in football are being considered following a string of controversies in the sport.

Tottenham were criticised last season for letting keeper Hugo Lloris continue playing after he had briefly lost consciousness in a goalless draw against Everton.

During the World Cup in the summer, Alvaro Pereira of Uruguay was left unconscious following a collision with England's Raheem Sterling, but was able to carry on playing after remonstrating with doctors.

The most accurate methods presently available for diagnosing concussion are time-consuming and involve brain scans.

Prof Belli and Dr Grey are keen to offer more options - both for longer-term decisions about a player's recovery, and eventually perhaps for pitch-side diagnosis.

"[Brain scans] are well and good for professional players. But what do we do for the rest of the country? What do we do for the academies and the schools, that don't have access to MRI scanners?" said Prof Belli.

"We just don't have enough MRI scanners in the country, for a start."

They are researching multiple possibilities, including blood tests for chemicals and biological molecules that are released when the brain gets injured, and a new test based on the brain's communication with the muscles.

This second proposal involves using a large magnet to activate small areas of the brain (called transcranial magnetic stimulation, or TMS) while recording the resulting electrical activity in muscles.

The scientists say all these tests show promise, and are closer to being developed than the breathalyser idea. These techniques could be used for "return to play" decisions following weeks, rather than minutes, on the sideline.

Dr O'Driscoll told the BBC he would warmly welcome any additional methods to objectively assess the health of players' brains.

"I think probably, looking at the research that's going on, we're probably not that far off it. It'll take a few years to prove it - it will have to be compared with other tests that we've got," he said.

'Life and death'

Medical experts are also concerned about the consequences of repeated, more minor blows to the head, which might not cause concussion but all together can produce permanent, sometimes devastating damage.

"It's not as if the brain doesn't get damaged by those lesser impacts," said Dr William Stewart, a brain trauma specialist at the University of Glasgow. "They may be just as important."

This includes the ongoing debate about the risks of frequently heading the ball in football.

A campaign on this subject, calling for long-term, detailed research, has been spearheaded by the family of former England and West Bromwich Albion player Jeff Astle.

Astle, according to an inquest, died from brain trauma caused by repeatedly heading footballs.

His daughter Dawn Astle, also present at the festival, said of players in any sport who try to cheat the concussion tests to get back on the field: "They just need to realise that it is about life and death."

Ms Astle added: "I think as a footballer, you expect to have knocks... you expect maybe to have arthritis later on in years. You do not expect to die of brain damage aged 59."

Follow Jonathan on Twitter, external.

- Published11 August 2014

- Attribution

- Published1 June 2014

- Published17 October 2013

- Published21 November 2013

- Published7 July 2014