Climate summit advances towards Paris deal

- Published

- comments

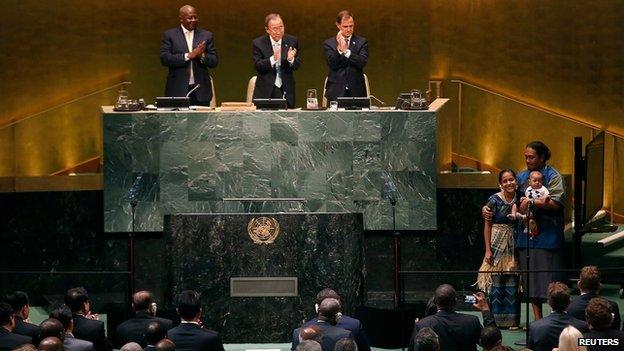

There was some cheer for Ban Ki-moon at the New York climate summit

Despite the absence of India and Australia, a majority of prime ministers and presidents did as Mr Ban had asked. They came to New York with pledges of action.

The French promised a billion dollars for the Green Climate Fund, a significant amount you might think, but miles from the goal of getting a hundred billion a year by 2020.

Following on from the Rockefeller Brothers Foundation divesting their dosh from fossil fuel, there were further significant announcements from institutional investors.

Two of the largest asset managers and pension funds in Europe, have connected with the UN Environment Programme to "substantially reduce the carbon footprint of $100bn of institutional investment worldwide".

And there was more - commodity traders Cargill, perhaps the very epitome of the type of industry that greens hate, announced that it would make its palm oil supply chains in Malaysia and Indonesia fully sustainable.

More than 150 countries signed a declaration that would end emissions from deforestation by 2030, though Brazil refused to join this coalition.

It wasn't just the Brazilians that had reservations. At least one forest NGO said it had "grave concerns" about the move.

Hannah Mowat from the group FERN wrote to the UN to say the deal didn't respect the customary rights of forest dwelling communities. There was no evidence, she wrote, that forests represent one of the most cost effective climate solutions.

Like many things connected to climate change, people agree on the big picture but fights break out over the pixels.

The star turn of the summit was President Obama, who underlined the importance of leadership from both the US and China on climate. He wanted a deal that would be ambitious, inclusive and flexible - a strong hint that he won't sign a legally binding treaty, which would require him to gain the approval of the Senate.

China's vice premier Zhang Gaoli reiterated the positive mood, stating to the surprise of many that the country's emissions would peak "as soon as possible".

But others reminded the meeting that it wasn't just about the big players - The success of a new deal would depend on how well it protected the weak as well as the strong.

"Every day the sea is rising, the coral reefs are dying," said Perry Christie is the prime minister of the Bahamas.

"But all the world has done is talk. The Bahamas calls therefore for a sufficiently ambitious, comprehensive, legally binding framework with commitments strong enough to reverse present upward emission trends.

"The survival of small Island states must be the benchmark for the 2015 agreement."

The Secretary General has shown himself to be a patient man and is doggedly determined to get a climate deal signed at a summit in Paris at the end of next year.

There are many opportunities ahead to fail, but this meeting did have unity and substance - a positive start on the road to a new global agreement.