Satellites detect 'thousands' of new ocean-bottom mountains

- Published

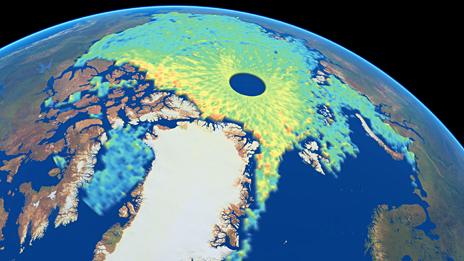

The new gravity data gives us our clearest view yet of the shape of the ocean floor

It is not every day you can announce the discovery of thousands of new mountains on Earth, but that is what a US-European research team has done.

What is more, these peaks are all at least 1.5km high.

The reason they have gone unrecognised until now is because they are at the bottom of the ocean.

Dave Sandwell and colleagues used radar satellites to discern the mountains' presence under water and report their findings in Science Magazine, external.

Using ship-borne echosounders is expensive and time-consuming

"In the previous radar dataset we could see everything taller than 2km, and there were 5,000 seamounts," Prof Sandwell told BBC News.

"With our new dataset - and we haven't fully done the work yet - I'm guessing we can see things that are 1.5km tall.

"That might not sound like a huge improvement but the number of seamounts goes up exponentially with decreasing size.

"So, we may be able to detect another 25,000 on top of the 5,000 already known," the Scripps Institution of Oceanography researcher explained.

Dietmar Müller: We know much more about the topography of Mars than we know about the seafloor

Knowing where the seamounts are is important for fisheries management and conservation, because it is around these topographic highs that wildlife tends to congregate.

The roughness of the seafloor is important also as it steers currents and promotes mixing - behaviours that are critical to understanding how the oceans transport heat and influence the climate.

But our knowledge of the seafloor is poor; witness the problems they have had searching for the missing Malaysia Airlines jet MH370, which is believed to have crashed west of Australia.

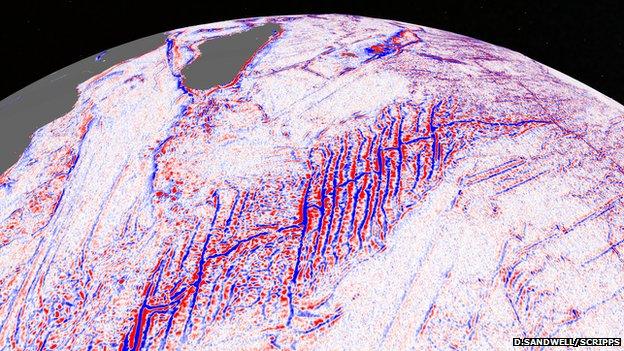

Seeing fracture zones tells scientists about the movement of the continents

The problem is that saltwater is opaque to all the standard techniques that are used to map mountains on land.

Ship-borne echosounders can gather very high-resolution information by bouncing sound off bottom structures, but less than 10% of the global oceans have been properly surveyed in this way because of the effort it involves.

Dietmar Müller from the University of Sydney said: "You may generally think that the great age of exploration is truly over; we've been to all the remotest corners of continents, and perhaps one might think also of the ocean basins. But sadly this is not true - we know much more about the topography of Mars than we know about the seafloor."

Satellite observations

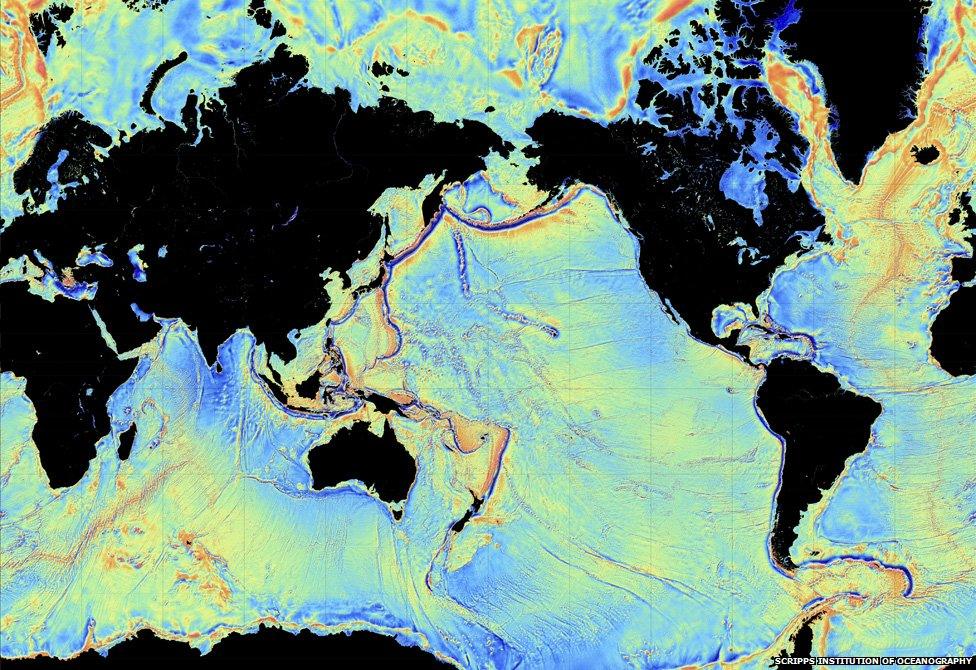

The alternative is an indirect method that uses satellites fitted with radar altimeters.

These spacecraft can infer the shape of the ocean bottom from the shape of the water surface above.

Because water follows gravity, it is pulled into highs above the mass of tall seamounts, and slumps into depressions over deep trenches.

Most of our maps of the gross outlines of mountains on the seafloor have relied on this approach.

Key advances were made using US Navy and European Space Agency satellites in the 80s and 90s.

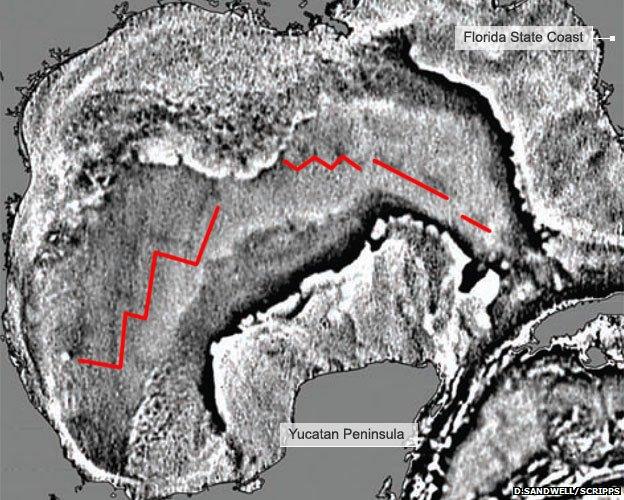

Gulf of Mexico: The jagged outline of an extinct spreading ridge is discernable

Now, Sandwell and his team have gathered new, improved datasets from more recent spacecraft - Jason 1, which was recently taken out of service, and CryoSat, which continues to orbit the Earth today.

Their denser coverage and better radar technologies have brought a two-fold improvement in the gravity model used to describe the ocean floor.

This richer information trove has barely been investigated yet, but already new discoveries are jumping out.

These include an extinct ridge where the seafloor spread apart to help open up the Gulf of Mexico about 180 million years ago.

And in the South Atlantic, the team sees the two halves of a different type of ridge feature that became separated roughly 85 million years ago when Africa rifted away from South America.

Biodiversity and Conservation: It is around seamounts that wildlife tends to congregate

The striking thing is that many such structures are often covered by deep sediments and only become visible in the new gravity data.

Seeing all the major fracture zones in greater detail is sure to be a boon to those who study the history of Earth's shifting continents.

The team hopes to improve still the resolution of its model.

This will come as Cryosat continues to take more measurements in the years ahead.

The irony here is that the European Space Agency mission is really dedicated to tracing the shape and thickness of polar ice fields - not the shape of the seafloor.

CryoSat's primary role is to measure the shape of polar ice surfaces - not the shape of the seafloor

"CryoSat's orbit and payload were designed to meet its primary ice mission goals, and extending its coverage to the ocean was on a 'let's see what we get' basis," said principal investigator Duncan Wingham. "As it has turned out, we now have a marvellous new view of the ocean floor."

For its ice work, CryoSat works in a specific high-resolution mode, which could be extended to more areas of the ocean to garner improved seafloor data - if mission time allows.

Ultimately, though, researchers would like to see a dedicated mapper that was specifically tuned to the task.

Walter Smith, a co-author on Thursday's Science paper, proposed just such a mission in 2001 called ABySS.

It was not accepted then, but the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration scientist believes the case is still a compelling one.

"The miniaturization of computer chips and the increase in CPU processing speed and data storage in the last 13 years has made it easy and cheap to do amazing things with radar," he told BBC News.

"There is still a lot we could do with a dedicated mission. It could be done - everything, 'soup to nuts' - for 100 million Euros (£80m), and the necessary technological innovations are well known to radar engineers in England, France and elsewhere. It is just a question of political will to find the budget."

Interpolation of ocean-floor shape by satellite

Most ocean maps are derived from satellite altimeter measurements

Satellites infer ocean-floor features from the shape of the sea surface

They detect surface height anomalies driven by variations in local gravity

The gravity from the extra mass of mountains makes the water pile up

In lower-mass regions, such as over trenches, the sea-surface will dip

Limited high-resolution ship data has calibrated the satellites' maps

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external

- Published4 August 2014

- Published23 August 2014

- Published27 May 2014

- Published24 April 2012