New cracks in Hunterston reactor

- Published

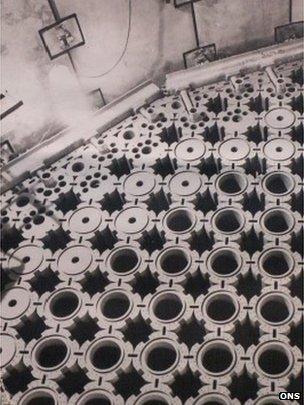

AGRs like Hunterston incorporated an array of cylindrical graphite bricks into their cores

New cracks found in the core of the Hunterston-B nuclear reactor could threaten operator EDF's plans to extend the Scottish power station's life.

Experts say fissures in two of the 3,000 graphite fuel bricks that make up its No 4 core are of a new type.

These "Keyway root cracks" are said to be more serious than previously identified fractures.

Safety rules stipulate that if the new problem gets above a certain threshold, the reactor would have to close.

Hunterston-B came online in 1976, and was due to close in 2016, but EDF, external wants to keep it running until 2023 and beyond.

The cracks might put the life extension timetable in question, and could mark the beginning of the end for Hunterston-B and the older Advanced Gas Cooled Reactors (AGRs), which generate around 15 % of UK electricity.

Serious distortion of the graphite core due to cracking could prevent the insertion of control rods, which are essential for safety and are used to shut down the reactor in an emergency.

"It is believed [the cracks] may eventually affect lots and lots of bricks, and it may be the life-limiting feature of the reactors," Dr Laurence Poulter, of the Office for Nuclear Regulation (ONR), external, told a group of experts meeting in Manchester recently.

He said there was no immediate impact on safety, but the new cracks were a "marker."

'Business risk'

Prof Paul Mummery, an expert in nuclear materials at Manchester University, said Keyway root cracking represented a significant new phase for the AGRs.

"Until now, it had only been a theoretical possibility, and some had argued these cracks might not happen at all, but that debate is now over."

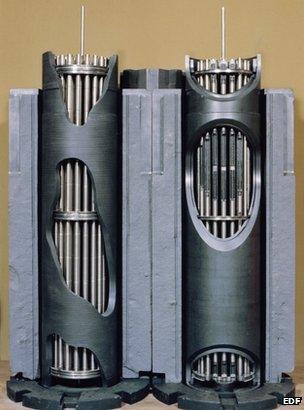

The new-style cracks occur in the channel, or keyway, that interlocks bricks

In response to a BBC inquiry, EDF's station director at Hunterston-B, Colin Weir, said the discovery was made during a periodic shutdown, which began in August.

"We found two bricks with a new crack, which is what we predicted during Hunterston-B's lifetime as a result of extensive research and modelling," he explained. The official said it would not affect the safety of the reactor.

The ONR regulator made no reference to the new cracks when it announced (1 October) that it was permitting Reactor No 4 at Hunterston-B to return to service on 8 October, after a two-month shutdown estimated to have cost EDF £60m.

The ONR said it was "satisfied that the licensee's justification to start up the reactor", and that it could operate for a further three years, documents on its website stated.

The next inspection at Hunterston-B will take place in 18 months, and EDF has "undertaken to review the inspection requirements", according to the regulator.

Acknowledging the future "business risk" for the company in a statement the ONR said: "If [EDF] find cracking that is within the safety case limit, but cannot show that it will remain within the safety case limit over the subsequent operational period - in that case, they would not be able to operate the reactor."

Prof Paul Mummery looks at the changes taking place to graphite bricks inside the reactor

The tubular graphite bricks, each about a metre high, moderate nuclear reactions and are essential to safe operation. However, they cannot be replaced.

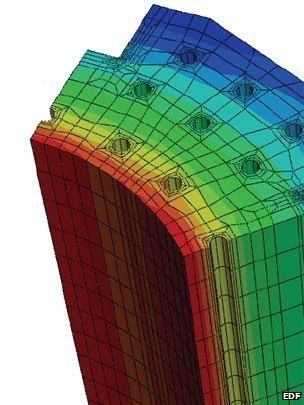

Years of neutron irradiation have caused the graphite to shrink, but because the bombardment does not spread evenly through the brick material, the rates of recession are also irregular. This causes tension and eventually cracking.

Experts at EDF maintain that the new cracks are from an anomalous group of bricks and that the reactors are well within the safety case, which allows for the general cracking of up to 300 bricks (10%) before the limit is breached.

The rates at Hunterston and its sister station Hinkley-B are between 1-2 %; the reactors at Heysham and Hartlepool are already up to 5%.

"It is proposed that we carry on using the AGRs as the rate of cracking increases, but there will come a point at which it is necessary to stop," Dr Poulter told fellow experts.

But predicting exactly when that will be is not easy.

EDF employs up to 200 people on its graphite programme dedicated to tackling the problems, and it is already investing £300m per year to keep its nuclear power stations running.

It's estimated a two-month stoppage alone costs the company about £60m in lost revenue.

Hinkley Point C should be completed early in the next decade

The AGRs generate the lion's share of Britain's nuclear electricity, and keeping them running until the planned new Hinkley C reactor in Somerset is completed in 2023, or later, is a key company objective for EDF.

"The question is whether it will be financially viable," says Prof Mummery.

The nuclear fuel assemblies, also clad in graphite, sit inside the bricks

"The reactors are creaking and showing signs of age. They will need a lot of work and investment to keep particularly the older reactors operating beyond the end of the decade."

But EDF were making the best efforts possible, he added.

The shrinkage issue is not the only problem Britain's AGRs.

A BBC investigation recently revealed that the graphite bricks were also losing weight due to oxidisation.

This could impact their long-term safety, especially in the event of a possible ingress of water.

EDF was granted permission by the regulator in the summer to relax its graphite weight-loss limit at the Dungeness reactor in Kent from 6.2% to 8% after it came close to breaching the original safety margin.

Hinkley-B and Hunterston-B are also getting close to their higher 15% limits, too.

The ONR said changes were safe.

Early history

In 2006, both reactors developed cracks in "ageing" boiler tubes", forcing the operator to reduce temperatures and make modifications to "mitigate" the effect of the "failure", according to ONR documents.

The interior brick material (red) is irradiated more than the outer layers

Reactors at Heysham and Hartlepool are currently offline after cracks were discovered in the heavy-duty "spines" that support the boilers positioned around the reactors, threatening their stability.

"This is a big one to sort out," one senior nuclear industry insider told the BBC on condition of anonymity.

"These are engineering challenges that must call into question how achievable the life-extension programme is."

Britain is struggling to find solutions alone.

Early nuclear reactors around the world all used graphite, but only the British and the Soviet Union persevered with the technology.

The USSR developed the RBMK design, which combined graphite with water as a coolant- a technology that went badly wrong at Chernobyl.

Britain opted for carbon dioxide as its coolant, and that is now causing some of the problems. Only the UK employed this particular solution.

As one nuclear expert put it: "I wouldn't say EDF can't do it but I wouldn't underestimate the challenges."

- Published22 September 2014

- Published29 September 2014

- Published4 September 2014

- Published4 December 2012