Robot snake learns secrets of sidewinders

- Published

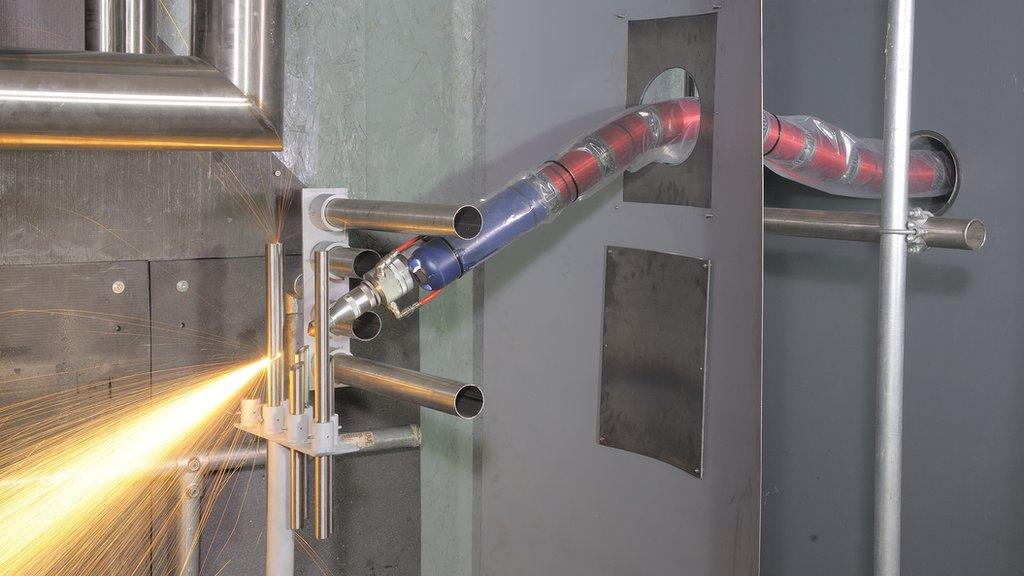

Physicists analysed the motion of sidewinders as they climbed an artificial sand dune

With the help of a robot, US researchers have described for the first time precisely how "sidewinder" rattlesnakes climb up sand dunes.

By observing snakes on an artificial dune, they found that on steeper slopes the animals flatten themselves to increase their contact with the sand.

They then tested the new insights with a robotic snake and calculated the best strategy for snakes - and robots - to scale sandy slopes without slipping.

The work appears in Science Magazine, external.

Unstable, granular surfaces like sand dunes pose a particular problem for animals and robots trying to traverse them.

Sand strategy

"We originally hypothesised that the way the snakes could ascend would be to dig their bodies more deeply into the sand, just like we would do on a sandy slope," said senior author Dr Daniel Goldman, who runs a biomechanics lab, external at the Georgia Institute of Technology.

That was not what he and his team found, however, when they painted reflective markers - carefully - on to six venomous rattlesnakes and put them to work on a tilting bed of sand, fresh from the Arizona desert that these snakes call home.

"One of the first surprises was how nice these animals are as subjects - they tend to just sidewind on command," Dr Goldman told the BBC.

Watch a rattlesnake, then a robot, climb a steep slope (footage: H Marvi and H Astley, Georgia Tech)

The next surprise, captured by several high-speed videocameras, was that instead of digging in for extra purchase, the snakes flattened themselves more smoothly against the sand, every time the researchers tilted the "dune" more steeply.

Furthermore, it was only sidewinding rattlesnakes - a species called Crotalus cerastes - that used this strategy. Thirteen related species of pit viper, faced with the same challenge, tried other wriggling techniques and got nowhere, with the exception of one: a speckled rattlesnake that inched its way very slowly up the incline using a concertina motion.

Sidewinders, on the other hand, Dr Goldman said, "could basically ascend any sand dune we threw at them".

To test out their findings in detail, Dr Goldman's team of physicists and biologists contacted robotics engineers at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh.

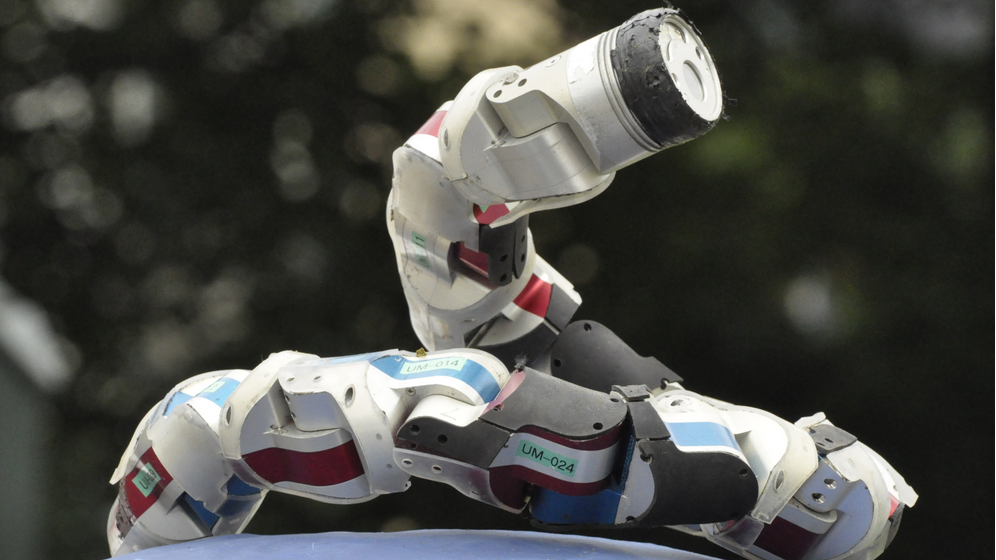

There, Prof Howie Choset and his lab, external had been working on sidewinding robots for several years. Their designs are aimed at various applications, from search-and-rescue to surgery.

But Prof Choset's robotic sidewinders were troubled by the very same challenge that the snakes had a knack for: sandy ascents.

The robot revealed details of the snakes' success but also learned from the animals about climbing slopes

A particular robot, nicknamed "Elizabeth", had failed on assignment in Egypt, slipping and falling on a slope within an archaeological site.

So the engineers brought Elizabeth to the artificial dune that Dr Goldman's team had built "in a shed out back of Zoo Atlanta", to see what they could learn.

Sure enough, using the insight from the rattlesnakes that flattening more of its body on to the sand would help with steeper slopes, the robot's performance improved.

Flow stopping

Adjusting Elizabeth's settings also allowed the collaboration to figure out other secrets to the sidewinders' success.

In particular, their motion boils down to a surprisingly simple combination of a horizontal and a vertical wave: a left-right slither, along with up-and-down movement, both travelling down the body but slightly out of sync.

"If you phase those waves just right, you get sidewinding," Dr Goldman explained.

Flattening or enlarging the vertical wave allowed Elizabeth to get just the right amount of contact with the sand. Too much, and the robot would slip; too little, and it risked tipping over.

The reason all these adjustments help the snakes and robots to climb is because they keep the sand more stable underneath them. Getting enough purchase without making too much sand flow downhill is a delicate balancing act.

"What we noticed was that when the snake's ascending effectively... the material behind it was in a nice solid state. And when we applied the changes to the robot, we found a similar feature of the interaction, such that the material didn't flow much," said Dr Goldman.

The key to successful dune climbing is maintaining just the right amount of contact, to keep the sand stable

Andrew Graham is the technical director at Bristol company OC Robotics, external, which specialises in snake-like robots. He said that although the Carnegie Mellon team were already known for their sidewinding designs, the new study was "a very thorough investigation of the efficiency of the process".

"They've looked at the whole problem, end to end, and demonstrated the application of what they've observed in nature to a robotic model," Mr Graham told BBC News.

He added that the insights from the snakes would help make Prof Choset's robots "more efficient and more applicable to different environments".

Follow Jonathan on Twitter, external

- Published20 August 2014

- Published30 January 2014

- Published29 April 2013

- Published27 March 2013