Egyptian Philae obelisk revealed anew

- Published

The obelisk has not been properly studied since it was erected on the Kingston Lacy estate

Fresh information is being obtained on the Philae obelisk, the stone monument that played such a key role in helping to decipher Egyptian hieroglyphs.

Today, the pink granite shaft stands on the UK National Trust's Kingston Lacy estate in, external Dorset, where it was brought from the Nile in the 1820s.

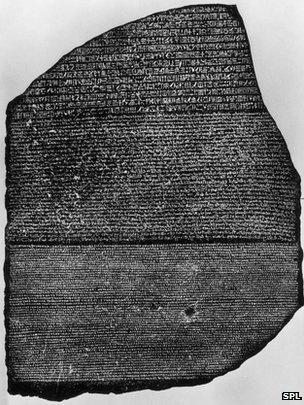

The obelisk's inscriptions, with those on the famous Rosetta stone, external, contained clues to interpret the ancient symbols.

Now, the monument is being studied anew with modern imaging techniques.

Oxford University researchers say their investigations are revealing markings that were previously too worn to be investigated properly.

"The last time anyone made a good record of what was on this stone was in 1821 when a lithograph was commissioned to celebrate the obelisk's arrival at Kingston Lacy," explained Dr Jane Masséglia from the Centre for the Study of Ancient Documents, external.

Greek is inscribed at the base; hieroglyphs run up the length of the pointed shaft

"We had no way of knowing that that drawing was correct. But our images show that whoever did the lithograph, especially of the hieroglyphs, made a really great job.

"The other big thing for us is the Greek inscription. Even when the obelisk first came to Kingston Lacy, people looked at it and said they couldn't make out the whole thing; there were large sections that were rubbed away.

"But we can now see the remains of that in a way no-one has been able to do previously," she told BBC News.

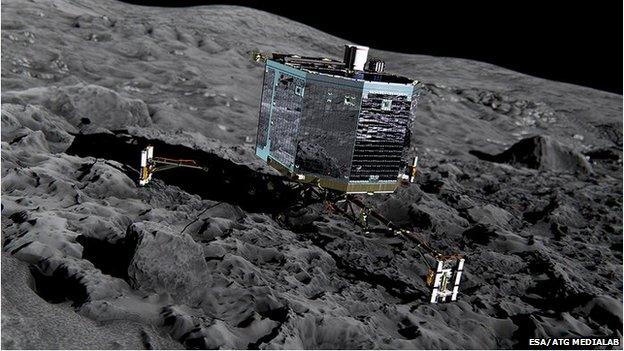

The study could not be more topical right now. Philae is also the name of the robot that the European Space Agency (Esa) intends in the coming weeks to land on a comet far from Earth.

This little probe is so-called because, like its Egyptian namesake, it too could provide valuable new insights on ancient times - the very beginnings of the Solar System, 4.5 billion years ago.

"The Oxford team like to say they are engaged in digital archaeology; we're also doing some archaeology, if you like - but in space," commented Esa's comet specialist Dr Gerhard Schwehm.

Philae should provide data to help scientists understand the origins of the Solar System

The toppled 2nd-Century BC obelisk was observed on the Nile island of Philae by adventurer and collector William John Bankes on one of his grand tours.

Dr Jane Masséglia: The obelisk celebrates an ancient tax break

He was so taken by it, he had the granite artefact transported to his family home in southwest England.

The obelisk carries Greek inscriptions at its base and hieroglyphs up the length of its pointed shaft.

It is the repetition of the names of ancient Egyptian kings and queens - Ptolemy and Cleopatra - in both writing forms that gave scholars important leads in their quest to translate the older of the two symbolic systems.

But part of the Greek text was always difficult to discern, and the obelisk's exposure to the British climate over the past 200 years has only made that task more difficult.

The obelisk was used with the Rosetta stone to help interpret the ancient symbols

The Oxford remedy is Reflectance Transformation Imaging (RTI).

This involves photographing a stone surface as it is lit from many different angles.

Although the shadows in any one picture will accentuate the relief, it is by combining the whole imaging series that the full topography becomes apparent, especially when colour and specular effects are carefully controlled.

Using RTI and other scanning methods on the obelisk has literally shone a light on those previously illegible sections.

"It gives us a good opportunity now to look at the relationship between the two inscriptions, to see if they're talking about the kings in similar ways - because there's the potential that they were appealing to different ethnic communities," said Dr Rachel Mairs, who is affiliated to both Oxford and Reading universities.

"You've got the hieroglyphs that are showing the king as a traditional pharaoh, and the Greek that might be saying something a little bit different to other people reading those inscriptions."

Philae hieroglyphs pictured in normal daylight (L) and using Reflectance Transformation Imaging (R)

The UK and European space agencies have taken the opportunity this week to highlight the Oxford research.

Esa is leading the mission to Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko, external, with the UK acting as a major contributor, in terms of funding and technology involvement.

On 12 November, the Philae robot will be dropped on to the surface of the 4km-wide ice body by its "mothership" - the Rosetta satellite.

Assuming it gets down safely, the contact probe will take samples to analyse 67P's chemical composition.

One of the onboard labs that will do this is called Ptolemy, developed by the Open University, external.

Because comets formed at the same time as the planets, scientists hope the Philae robot's data can inform them about the chemistry and physical processes that went into creating the Solar System.

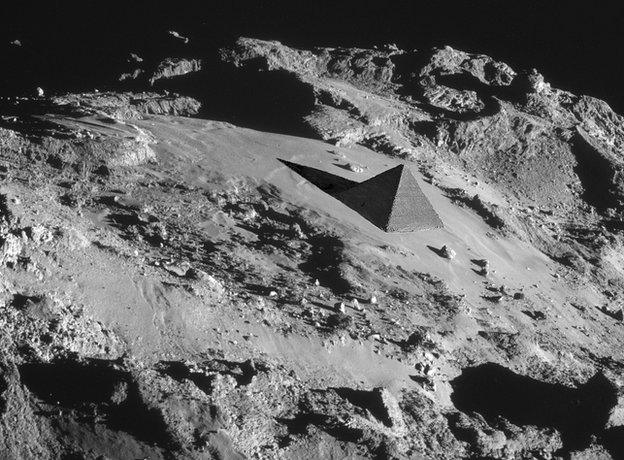

Egyptian theme: A superimposed Cheops pyramid gives a sense of scale to the terrain on Comet 67P