Crystal beauty: Illuminating the structure of matter

- Published

To reveal the structure of molecules, scientists use a process called X-ray crystallography. Now a photographer has captured images featuring details of the technique, illuminating the structure of matter itself.

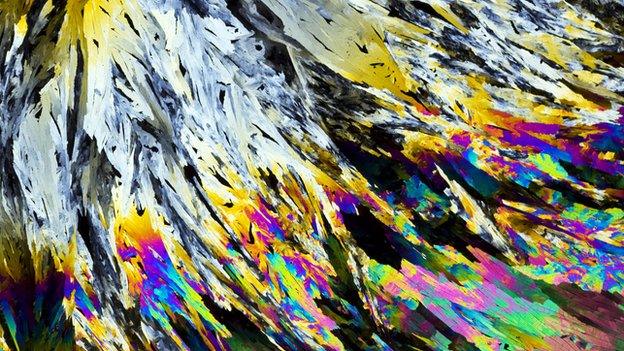

The rapid crystallisation of the proprietary cancer drug shown here mimics the metamorphosis from the early years of cancer treatment to life-saving drugs available today

The world of science and art merging is nothing new, but crystallography is seen by some as an art form in itself.

That's why photographer Max Alexander was brought on board - to capture the beauty of crystals and to profile the scientists behind the work. He had previously produced an exhibition at the Royal Albert Hall called Explorers of the Universe, external.

Now as part of the International Year of Crystallography, soon drawing to an end, Mr Alexander has gone from the very large to focussing on the importance of the extremely small.

His new exhibition, Illuminating Atoms, presents the work of crystallographers through portrait and documentary photography.

It is part of a long-standing tradition at the Royal Albert Hall of showcasing and promoting cutting-edge science, first introduced by Prince Albert's Great Exhibition of 1851. Ever since, this cultural hub of London has been known as "Albertopolis".

Margarete grows crystals of biological molecules which are analysed by X-ray crystallography in order to understand how they interact with potential new medicines. The crystal on her pupil is a reflection from her computer screen

Crystallography is a way of finding the shape of molecules and deducing their atomic arrangement.

First, crystallographers must turn what they want to study into a crystal. This arranges the atoms in a structured and ordered way.

It is by shining X-rays onto the crystal that scientists can find out the three-dimensional arrangement of the molecule. The diffracted X-rays are then detected while the crystal is rotated.

Understanding the shape and structure of molecules helps scientists to figure out how they work.

As mentioned in a previous feature when BBC Radio Science covered the start of this celebratory year of crystallography, in the words of Nobel laureate Max Perutz it shows "why blood is red and grass is green, why diamond is hard and wax is soft, why graphite writes on paper and silk is strong".

Indeed if it wasn't for breakthroughs in this field, Francis Crick and James Watson would not have been able to discover the double-helix structure of DNA.

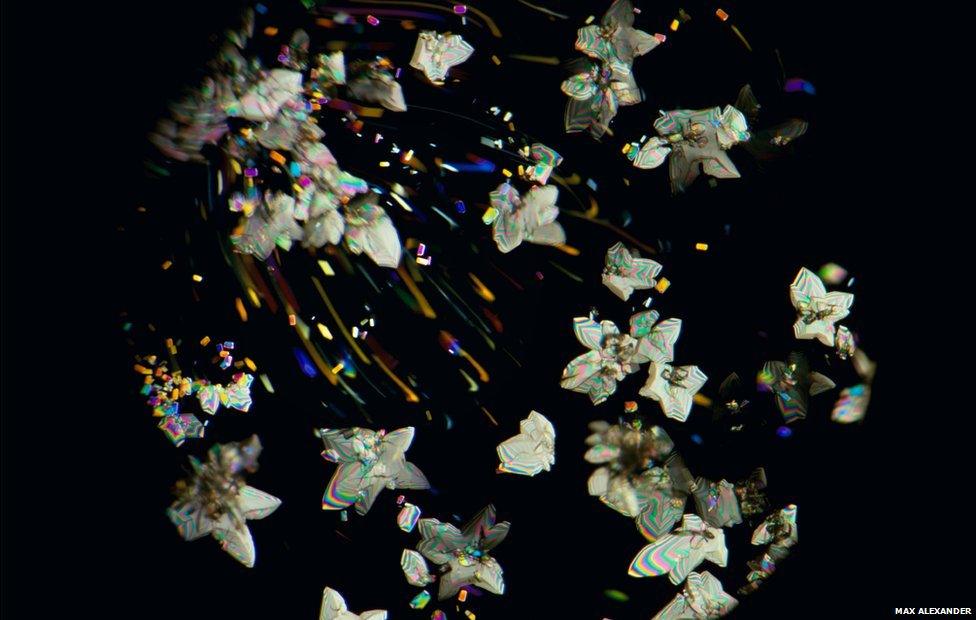

Centrosomes are molecular machines that organise the process of cell division in the body. To understand this process better, scientists try to grow crystals and solve the structures of the proteins from which they are built. These crystals are of a protein that co-ordinates the assembly of this important machine.

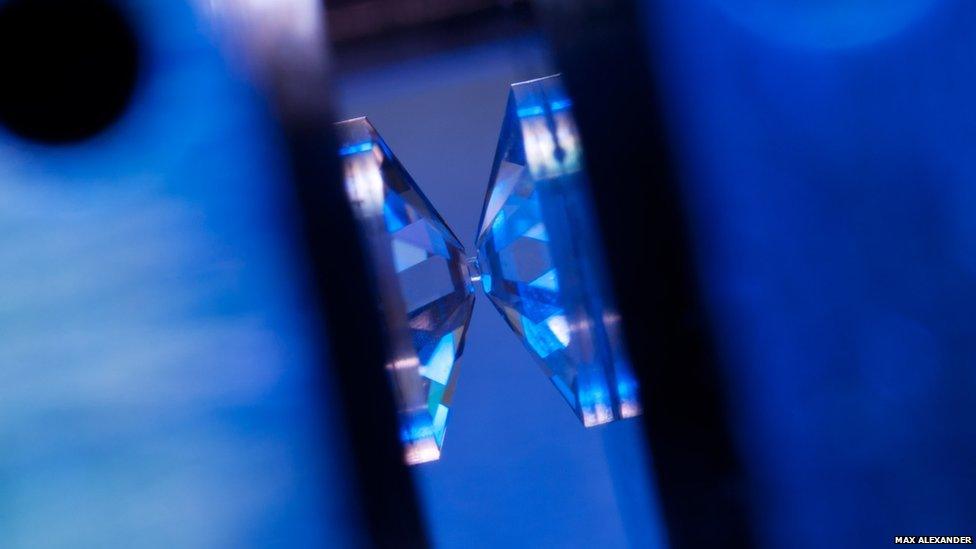

Diamond is one of the hardest substances known. Squeezing a tiny crystal between diamonds subjects it to extreme pressures, making the crystal structure change. The crystal can experience conditions like those deep in the earth's crust, where minerals like rubies and emeralds are formed.

"Crystallography is very much a field of science that lends itself to an artistic approach. It's not just about pattern recognition," says Mr Alexander.

"These [scientists] are people working at the cutting edge of science. The impact they have across all number of sciences is little known."

This includes fields like drug discovery and vaccine development.

There's a massive crossover between science and art, he adds. "Scientists are very creative people, to draw this creativity out of them helps reconnect the science to the public."

Crystallographer David Keen (pictured) studies crystal structures that behave in unusual ways when their atoms become disordered. Hundreds of holes were dug in the sand in Porthcawl beach in South Wales to portray the neutron diffraction pattern from a quartz crystal which is a component of sand

The exhibition comes in two categories, portrait images like this one of crystallographer David Keen (above) who worked with his students to draw a diffraction pattern in the sand. The second aspect is a documentary strand - a selection of which are featured here.

His aim was to tell the story of crystallography around the UK and to showcase some of the facilities used to study its applications.

"Aspects of science can be very difficult to understand but if you can find simple ideas and use those concepts to get those across, that helps to connect the public. Making that connection is paramount to what I do," explains Mr Alexander.

Pharmaceutical materials display different properties depending on the arrangement of molecules in their crystal structure. Needle-shaped crystals are often difficult to analyse but finding the right crystal is the first step in the development of treatments for diseases such as malaria.

Working together with crystallographers was an important part of the project. One of these was Elspeth Garman, professor of crystallography at the University of Oxford, in charge of introducing the exhibition.

"They're really interesting photographs that make you think about various aspects of crystallography, beautifully expedited. I'm honoured to be introducing them," she says.

"It opens up a new set of people that might be engaged with crystallography and the science, just as we're engaging with the arts.

"My challenge will be trying to communicate what we do and the aesthetic beauty of it to the people who are more on the arts side, it's a fantastic opportunity which can only expand the knowledge, excitement and beauty of the field," Prof Garman adds.

A crystal is placed on the end of the pin with a stream of cool air coming in from the right. The X-ray beam arrives from the silver pipe and the camera images the crystal.

Technicians here are forming a fan blade for a jet engine from titanium alloys, by injecting high-pressure argon gas at around 1,000C. Crystallography experiments carried out on these blades helps to understand how their performance is affected by the materials used in the manufacturing process.

Workers at a lab in Oxford celebrate when a new crystal structure is determined. It can take many years to grow, measure its diffraction pattern and solve its structure.

The exhibition, external is now available to view at the Royal Albert Hall until 07 December 2014.

- Published18 December 2013