Will Obama's climate surprise deliver a global deal?

- Published

- comments

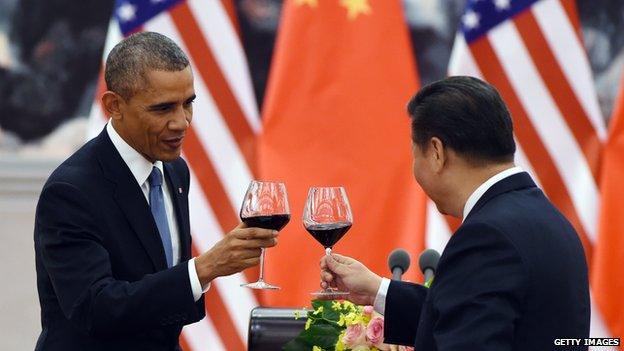

China and the US agree a deal on climate but does it bring a global treaty any closer?

We are a fickle bunch, us earthlings.

Back in 2009, the US signed the Copenhagen Accord, external and pledged that they would cut their emissions in 2025 by 30% compared to 2005 levels.

The world hissed and booed, and called it a failure.

Today, in an "historic" agreement announced with China, the US are committing to cutting their emissions by less than that, (26-28% by the same date) and the world is cheering, external.

It is the same with China.

In the agreement, the Chinese promise not just to peak their emissions by 2030 but to increase the share of non-fossil fuels in their energy mix to 20% by the same date.

Strangely, earlier this year a report from analysts GlobalData suggested that China is already on course to get 20% of its energy from greener sources by 2020, external.

So where is the history in all these histrionics?

The agreement does marks a significant moment with China, for the first time, naming a date when their emissions will peak.

But the deal doesn't stem from a philosophical determination to save the planet.

It is based on the naked political necessities of both countries.

President Obama needs to show the US Congress and public he can create a level playing field for American industry to compete with China.

President Xi Jinping needs to show the Chinese people that he is making significant efforts to clean the air by reducing the use of coal, while maintaining China's efforts to lift people out of poverty.

Impact on UN

But in terms of steering the world to below the 2 degree C target, external that scientists believe is the threshold of danger, this agreement doesn't cut the mustard.

"This does not put us on a pathway to 2 degrees," said Samantha Smith from WWF.

"This announcement is a political signal from these two countries. If we understand it as a signal, it is a good thing and it is a first for China to stand up and say it will cap it's emissions."

The China-US step also received a muted welcome from the Alliance of Small Island States, external, (Aosis) made up of countries facing threats from rising sea levels.

"We look forward to more detailed information about how the commitments match up against what is needed to ensure a safe global climate," the Aosis ministers said in a statement.

"We recognise the importance of bilateral cooperation between these two countries, but the numbers must add up," they added cautiously.

The real significance of the US-China deal is the changes it signals in the UN political process.

Every nation has committed to agree a new deal, external by the time the parties get together in Paris next year.

Next month the negotiators will meet in Peru to draft the text of that agreement, external.

What has blighted that whole process has been a very basic division over definitions - who is rich and who is poor?

The developed countries agree that they will take on the biggest burden of emissions cuts, but they insist that the richer developing nations must do so too.

Solving air quality issues from the use of coal is critical for the Chinese leadership

This has been strongly resisted by many of these emerging economies, including India - They point to the hundred of millions without electricity in their country and say they will resist attempts to limit their use of coal, which they say they need to develop.

According to some observers, the Beijing deal is significant because it underlines the fact that China is changing its position.

"It signals a shift," according to Liz Gallagher from environmental think-tank E3G.

"At the highest level there is a recognition that China isn't a deeply poor society and that they are distinct from other developing countries.

"I wouldn't say they have lumped themselves in with the US and EU, it is almost like a transition they have committed to."

As well as putting pressure on the developing countries to move on from a simple, binary view of the world, the deal should also put pressure on some developed countries who have been moving away from tackling emissions.

"The ball is in play, so now others, not just developing counties but the likes of Japan, Canada and Australia, there is now pressure on them to come forward with something themselves," said Samantha Smith.

Taken together with the EU's recent announcement of new climate targets for 2030, external, you could be forgiven for thinking that a deal in Paris is in the bag.

If only.

Cutting emissions is just one part of the negotiations, and for many countries, the least important bit.

For many, the bigger questions are about cash to cope with the impact of climate change.

Many nations want a financial mechanism that would put a legal responsibility, external on those who have done most to cause climate change to compensate those who suffer most from it. This is a potential iceberg for the whole process.

"There is a need for the developing countries to see that there would be certainty in terms of future flows of finance, otherwise we won't see much ownership of this process from many of the parties in Paris," said Tosi Mpanu-Mpanu, a senior negotiator from the Democratic Republic of Congo, speaking to me earlier this year.

And no deal without it, I ask?

"I'm not afraid to say so," says Mr Mpanu-Mpanu.

"No money, no fund, no deal in Paris."

Follow Matt on Twitter @mattmcgrathbbc, external.

- Published2 November 2014

- Published10 November 2014

- Published12 November 2014