Rosetta: Elation and woe of Philae comet landing

- Published

For Rosetta's scientists and engineers gathered from across Europe, the last few days have been more gut-wrenchingly emotional than anyone imagined.

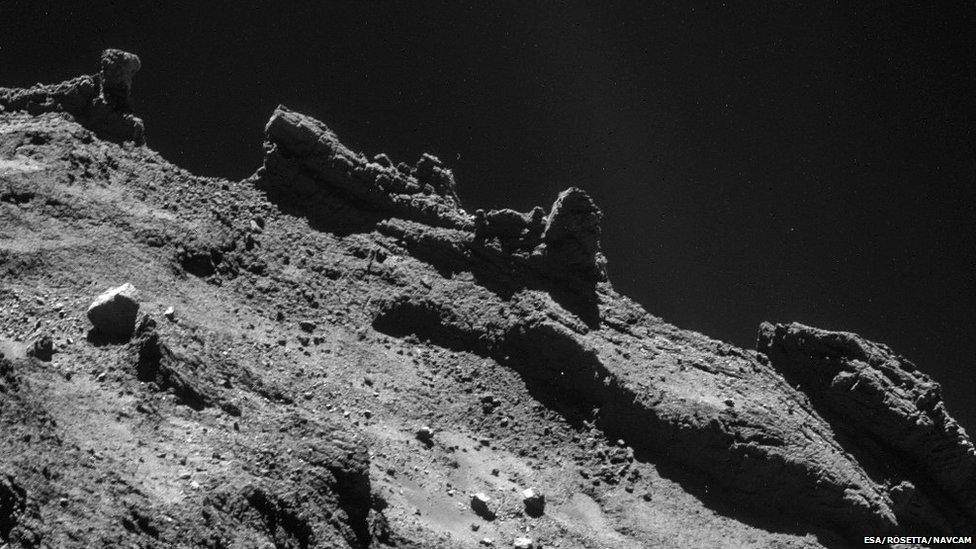

From the moment when the tiny Philae lander was released to plummet towards the surface of Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko to the last desperate hours on Friday evening when the team scrambled to get every drip of science, the story has veered from elation to near-panic with alarming speed.

A mission that was already a success has become an engineering triumph, says Dr Lintott

The plan for Philae's stay on the surface had been made assuming the worst, and each of the 10 instruments it carried was to get its turn within the 60 hours or so of life allowed by its onboard battery.

I've just come back from mission control, and as the mood among we observers turned sombre, there was laughter in mission control and champagne corks popping at lander control just up the road.

As it became clear that the plan had worked well, and critically that no bit or byte had been left stranded on the fading lander, a mission that was already a success became an engineering triumph.

Yet it was, if I'm honest, hard to concentrate on that. Philae is a robot, of course, a project of human ingenuity that did the tasks it was assigned, to the limits allowed by the performance of its components and the situation it found itself in.

That's all there was to it, but it was impossible not to want it - to will it - to succeed. As its power went out, I'm sure the team found themselves wanting more, and mechanical fact became a drama followed by tens, or hundreds of thousands on Twitter and on the web.

So where does Philae's brief existence sit in the pantheon of space age dramas? Two comparisons spring to mind immediately. First, Apollo.

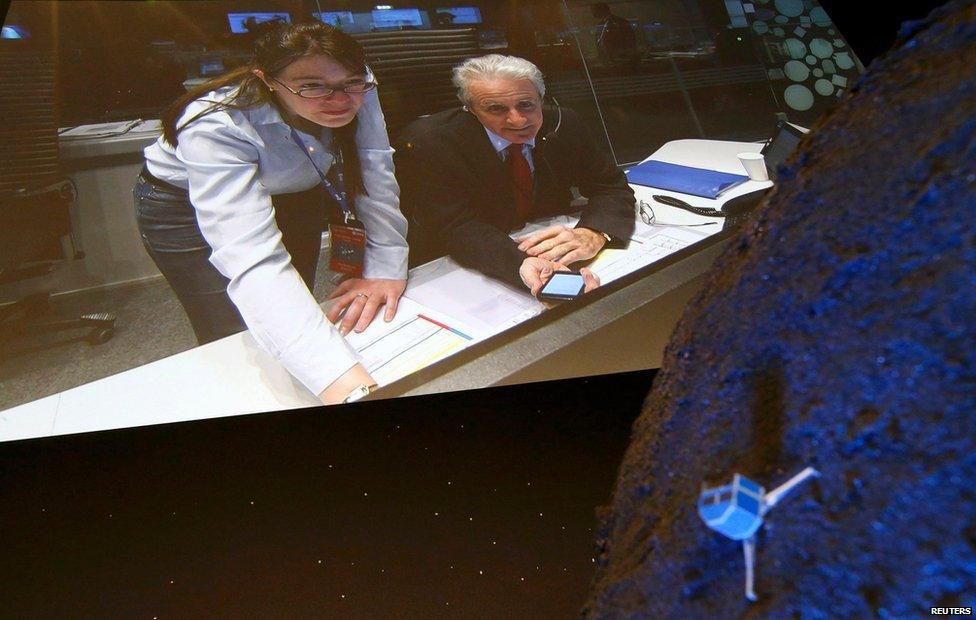

Esa worked to ensure that "no bit or byte" of science data was left behind on the lander

I'm not old enough to have watched, and at times this week I got a flavour of what it must have been to follow those legendary missions. Apollos 11 and 13 - both successes in their own way - captured the attention of the entire globe, changing the way we see our world forever.

Philae can't make that claim, but it has a strong link to the scientific legacy of Apollo. The rocks brought back by the astronauts from the lunar surface told us about the early days of the Solar System, just as the results beamed back from this frozen fossil of a comet will tell us about the Earth's origins.

The scientific legacy of Philae - and the Rosetta mission more generally, of course - will continue Apollo's legacy.

The Mars landings carried out by Nasa in the last few years are a second obvious comparison, particularly the Curiosity rover's "seven minutes of terror" as it was lowered to the surface by a hovering platform known as a skycrane.

Curiosity's mission is ongoing, but the cadence is very different. In ramping up the emotional pressure, Philae's slow descent to the surface over nearly seven hours, followed by a short, sharp encounter with a bouncy comet beats the slow and steady exploration of Mars - no matter how important and exciting that is.

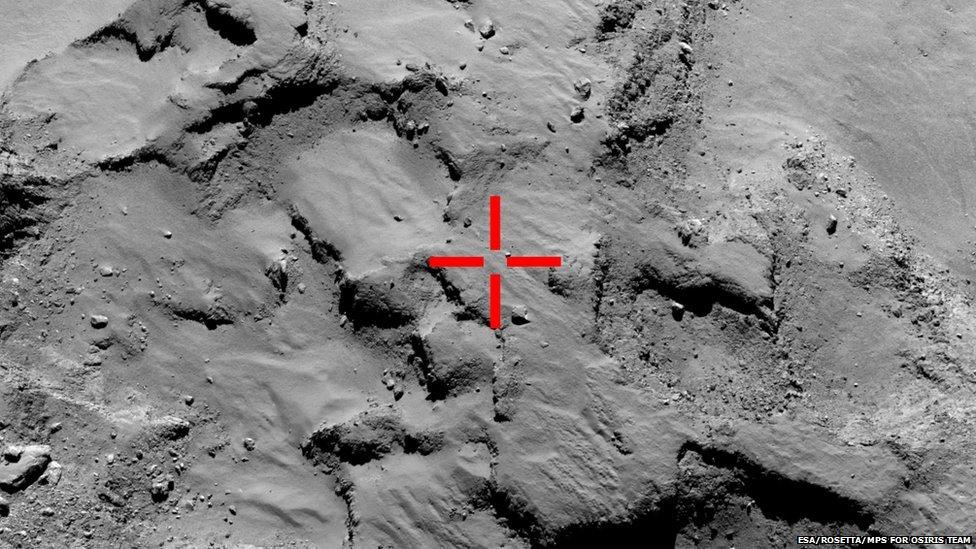

Scientists have been trying to locate Philae, which bounced twice on the comet before settling down

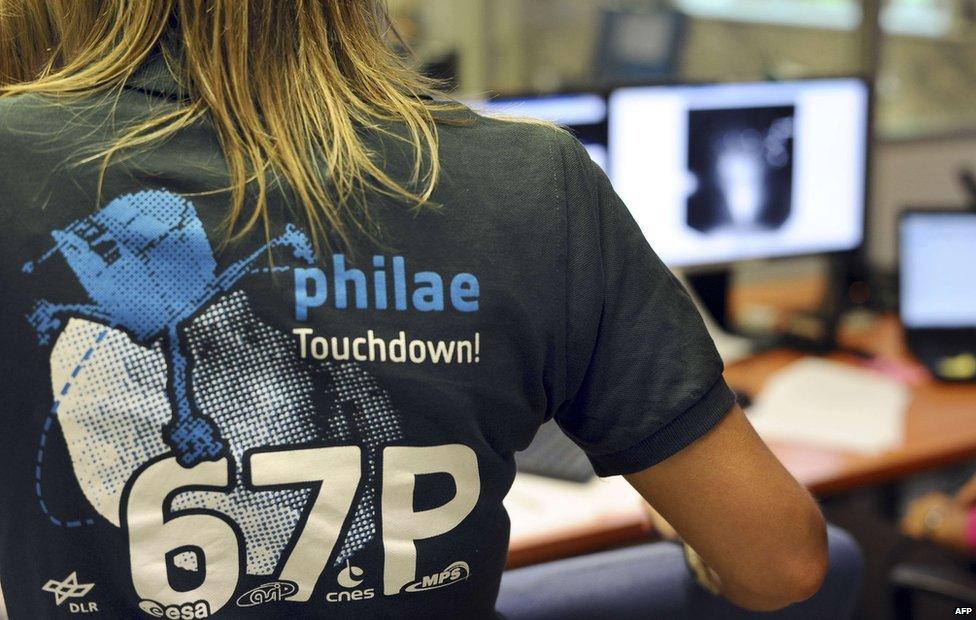

The story has veered from elation at the successful landing to near-panic

Comparisons such as these are ultimately just a way of trying to understand why missions like Philae make us feel the way they do.

But one group of people will be pleased by this mission's success in particular. Rosetta was the most ambitious and audacious mission the European Space Agency (Esa) has ever undertaken, and while the mission would have been a scientific success without a successful landing, it would have been a public relations disaster had Philae failed.

So used are the press and public to Nasa's successes in space that there was almost a cultural cringe in place, as reporters scrambled to get Americans to explain how clever we Europeans were being.

Today, Esa's remarkable skills are there for all to see - Philae's first landing point was within 10m of the target, an almost literally unbelievable result after a 10-year journey.

The real legacy of this week might be a rejuvenated European space effort. Missions to Mercury, to swoop close to the Sun and, hopefully, to Mars are already planned, and there are no shortage of other ideas.

The challenge now is for the Esa leadership to turn Philae's success into political capital - and ultimately funding.

Chris Lintott is co-presenter of the Sky at Night, which will present a Rosetta special from inside the heart of mission control on Sunday night - 9pm on BBC4.