UN climate deal in Peru ends historic North-South split

- Published

The Cook Islands are one of the "frontline states" particularly vulnerable to climate change

Unexpectedly, for a city that is in a desert area, rain drizzled from the night-time sky over Lima early on Sunday.

Just as unexpectedly, the gavel came down on UN climate talks that had almost collapsed because of wide gaps between the positions held by rich and poor nations.

So how was the agreement reached? And does it take the world any closer to dealing with climate change?

The Lima deal can be seen as a dry run for a much greater Paris compact. Ostensibly it was about how countries should format their intended national pledges on climate change.

In reality, it was about much weightier issues. It asked the 194 countries that came to the Peruvian capital if they were really serious about a long-term global climate deal.

It the answer was Yes, then some sacred cows would need to be sacrificed.

Prime among them was the binary view of the world that the UN convention on climate change brought into being in 1992.

Distinction ditched

It divided the world into rich and poor (Annex 1 and Non-Annex 1, in UN jargon). The richer countries would take on carbon-cutting commitments - the poorer ones would not.

Here in Lima, that old fashioned view of the world was consigned to history, though not without a desperate struggle.

Activists called on world leaders to make big commitments at the talks but left disappointed

Developing countries resolutely fought to keep this sense of differentiation firmly in the text. They were very upset when the original text about the pledges countries will make next year, used the word "shall".

It seemed to them that poor African countries and small island states were being corralled into making the same level of commitment on climate change as the big boys.

No one seriously expects the countries in sub-Saharan Africa will have to do the same as the US and the EU. Eventually the "shall" became a "may".

But when you have a situation where countries like Singapore, with a gross domestic product per capita larger than Germany, are still classed as a Non-Annex 1 ("poor") country, you can see why there were calls for reform.

As Matt McGrath reports, the agreement is the result of 48 hours of negotiations

So there is no mention of Annex 1 parties anywhere in the document. To make it clear there are different strokes for different folks, the text reiterates the importance of "common but differentiated responsibilities", or CBDR in the jargon.

But it adds an important rider: "in light of different national circumstances."

I am told that both China and the US supported this addition. Essentially it means there will be no fixed positions anymore. Countries can and do develop, and with that development will come a different level of commitment on climate change.

Hope for Paris

According to the executive secretary of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change, Christiana Figueres, this was extremely significant.

"There are three pieces of that concept," she said. "One is the historical responsibility, which is undeniable, of industrialised countries; next is the respective capacities and capabilities of countries, which are an ongoing process; and the third part is actually the national circumstances.

"From a political and operational point of view it is a very important breakthrough that actually opens the way towards a Paris agreement."

The historic distinction between rich and poor countries was abandoned, but not without a fight

Others agreed. This change was painful for some but it had to happen, said Liz Gallaher, from the think tank E3G.

"What we've had in the past is this north-south divide, and what this text does is to break that up, it's much more fluid," she added.

"There is lot of sense of differentiation, how do you apportion responsibility between countries rather than this north versus south which is great."

Green campaigners, though, are very upset with the Lima process. Too little had been achieved, too many decisions had been kicked down the road, they said.

"These talks delivered basically nothing for the poor and vulnerable in developing countries," said Harjeet Singh from Action Aid International.

"More exciting than the negotiations were the sheer number of impacted peoples marching in the streets in Lima and staging actions at the talks - the people who have the most to gain or lose from these talks. How long will governments continue to ignore people's demands?"

The goal of zero fossil fuel emissions by 2050 could now be a possibility

While the focus has undoubtedly been on the issue of pledges and the arguments about them, another important concept has quietly crept into the broader document.

This is the idea that a long-term goal for climate change might not be just keeping temperatures below 2C, but zero emissions from fossil fuels by 2050.

The idea has the backing of scientists, and now it is in the rough negotiating text.

It that was to remain in the final deal in Paris, it would be an idea that could, quite literally, change the world.

But there is a long way to go.

The ghosts of Copenhagen are everywhere in this talks process. One of the reasons Lima has been so important is that it got everyone to say what they will do, before they arrive in the French capital next year. That hopefully overcomes one of the key problems that saw efforts founder in Denmark five years ago.

But despite that, the Lima deal does have a critical weakness. There is, as yet, no meaningful way of ratcheting up the commitments countries make. That was sacrificed to keep the developing nations on board.

It is not the only can that has been kicked down the road and the big danger is that leaving too much to the last minute in Paris will ensure a repeat of the failings of Copenhagen.

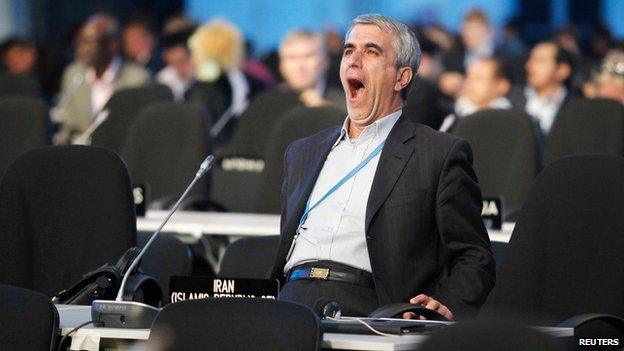

The round-the-clock talks, running two days over schedule, were an exhausting process

Journalists caught up on sleep while they waited for the final text of the negotiations to appear

- Published14 December 2014

- Published20 September 2013