SpaceX launches cargo ship but rocket recovery test ends in crash

- Published

SpaceX successfully launches an unmanned cargo mission to the ISS

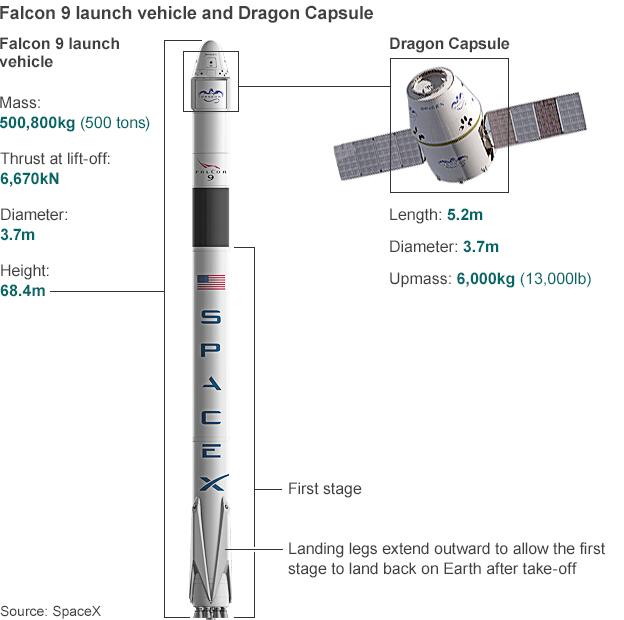

The American SpaceX firm says its experiment to bring part of its Falcon rocket down to a soft landing on a floating sea platform did not work.

The vehicle was launched on a mission to send a cargo capsule to the International Space Station.

But once the first-stage of the rocket completed its part of this task, it tried to make a controlled return.

The company CEO Elon Musk tweeted that the booster had hit the platform hard.

"Close, but no cigar," he added. "Bodes well for the future tho'. Ship itself is fine. Some of the support equipment on the deck will need to be replaced." And he continued: "Didn't get good landing/impact video. Pitch dark and foggy. Will piece it together from telemetry and... actual pieces."

SpaceX intends to keep trying. If this kind of capability can be proven, it promises to dramatically lower launch costs in the future.

It would mean that normally disposable rockets could be recovered, refurbished and re-used.

It might also point to new ways of bringing spacecraft back down to Earth in general.

Lift-off from Cape Canaveral, Florida, for the Falcon 9 with its Dragon freighter occurred at 04:47 local time (09:47 GMT). The cargo ship was confirmed in orbit and en route to the ISS nine minutes later - at about the same time the first stage was expected at the drone ship. Dragon's arrival at the station is set for Monday.

This is the first American re-supply mission to the orbiting platform since October's spectacular explosion of a freighter system operated by competitor Orbital Sciences Corporation.

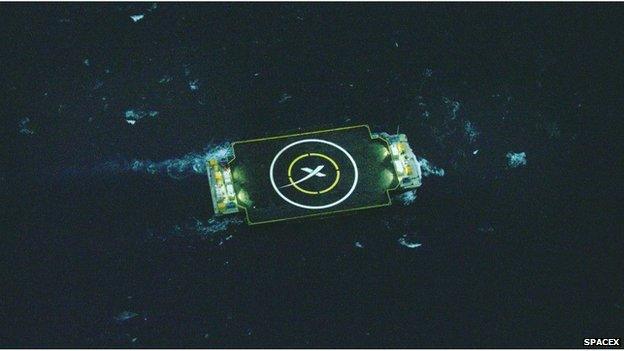

The landing platform was stationed 300km northeast of the Cape. It sustained some damage in the attempt

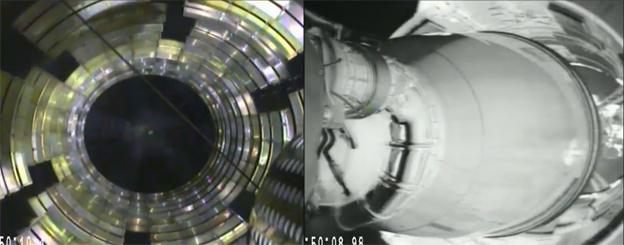

The Falcon's onboard cameras capture the moment the first stage separates to begin its return

Traditionally, rockets have had an expendable architecture.

As they head skyward, they dump engines and empty propellant tanks to save the weight that allows their upper-stage, including the satellite payload, to make the jump to orbit.

Any discarded hardware simply tumbles back towards the planet and is torn apart.

And this approach means every new mission needs an expensive new rocket.

SpaceX, on the other hand, believes it can recycle key elements of its rockets.

It has been testing first-stage boosters that relight their engines to try to slow their fall through the atmosphere, attaching fins to help guide them downwards and legs to make a stable touchdown.

Until Saturday, these were all mock landings, in which the stage was brought to a hovering position at the surface of the ocean, where, without a solid platform to set down, every booster was then subsequently lost into the water.

This latest experiment marked the first use of the drone platform.

SpaceX conceded that reaching this touchdown pad at the first attempt would be an immense challenge.

The barge is less than 100m wide, and all previous experiments had been working on a landing accuracy of some 10km.

Nonetheless, the company will be encouraged that it got so close to the platform.

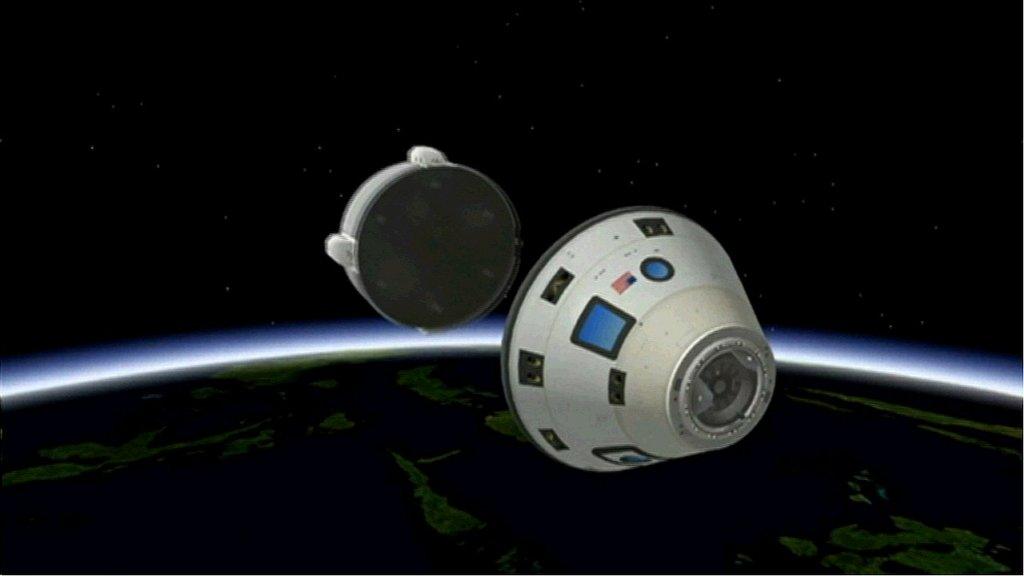

The Dragon deploys its solar panels (L) as the Sun rises over the Earth's limb (R)

Analysis

By Jonathan Amos, BBC science correspondent

Reusability in rockets has been studied for decades. On the face of it, it seems extremely attractive, says John Logsdon, professor emeritus at the Space Policy Institute, George Washington University.

"Because launches would be cheaper you can afford a failure. That means you can design satellites that are much less expensive; you won't have to spend so much money to ensure they work, because if they don't work another launch is relatively cheap."

And Dr Adam Baker, the director of the Rocket Lab at the UK's Kingston University, concurred: "Space exploration is currently extremely expensive. If SpaceX is successful in reducing the cost by 50% or more, more space applications become possible - more satellites, more benefits and services to society from space, for example space solar power, and potentially more astronauts.

"There could be more flights into space for you and I, expeditions to the Moon, exploring Mars, perhaps colonising Mars and going further out into the Solar System."

But realising these benefits is not so straightforward.

People will remember that the space shuttle was designed as a partially reusable system, and yet the complexities of refurbishing the vehicle swamped any savings. The shuttle main engine - an engineering marvel - contained 50,000 parts.

SpaceX has to avoid this trap if it is to make reusability practical. It says its Merlin engines should be able to complete 40 firing cycles without significant parts exchange.

And they would also have to get satellite operators comfortable with the idea of launching their precious hardware on what would essentially be second-hand rockets.

"The customer doesn't ask for reusability; they ask for reliability at the cheapest cost possible," said Rachel Villain, with the space intelligence company Euroconsult.

"Reusability is the problem of the supplier, not of the client. A satellite operator has basically three demands - on time, on quality and on price," she told me.

Whatever results from SpaceX's experiments, the California-based outfit is certainly making the rocket industry sit up.

It already offers commercial launch prices that undercut its competitors, and Europe has been so alarmed by the American firm's progress that it has ordered a new, lower-cost version of its Ariane rocket, which should enter service in 2020. It will not, however, be reusable.

It will be interesting to see how competitors like Ariane further react if SpaceX makes a real go of reusability.

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external

- Published6 January 2015

- Published3 December 2014

- Published29 October 2014

- Published16 September 2014

- Published25 April 2014