What does Beagle2 say about how to handle failure?

- Published

- comments

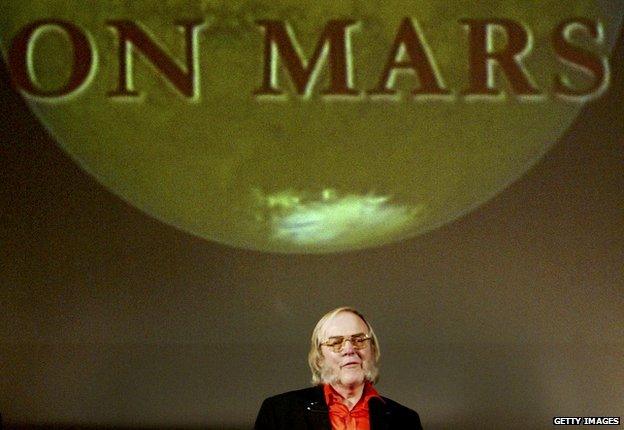

Images show the daring mission, masterminded by the late Colin Pillinger, came tantalisingly close to glory

The discovery of Beagle2 on the surface of Mars confirms the mission as one of most glorious near-misses in the history of British exploration.

Bold, imaginative, and brilliantly-engineered, the spacecraft came very close to upstaging Nasa but ultimately failed.

Criticised by some for relying too much on the British tradition of "winging it with string and sticky tape", as one European space official put it, Beagle2 nevertheless caught the public imagination.

The mastermind behind the venture, the late Colin Pillinger, could have had a very successful career in marketing. Shyness was never an option.

His choice of the mission's name - after the vessel that had sailed Charles Darwin around the world - deliberately aligned it with one of the greatest journeys in the story of modern science.

Just as Darwin's venture had ultimately led to a revolution in scientific theory about life on Earth, Pillinger's was designed to answer the big question about life beyond it.

Distinctive whiskers in full bloom, mind fizzing with ideas, he and his wife Judith shuttled their very British Land Rover between the centres of power of the European Space Agency, hustling for support.

They enlisted help from some of the most fashionable names in British art and music: commissioning the artist Damien Hirst to paint the image that would calibrate the camera and the rock group Blur to compose the first transmission signal.

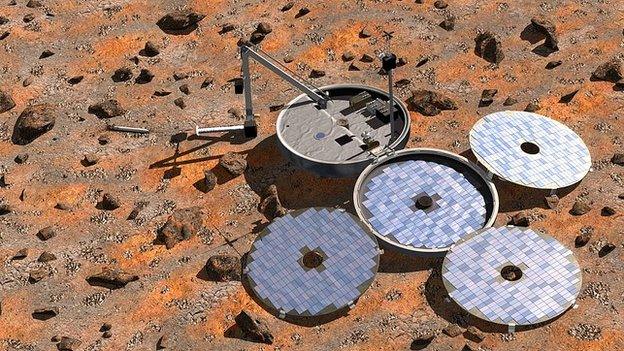

This artist's impression shows how the lander was to have deployed its sampling tools on Mars

And once, while filming a story at Pillinger's lab at the Open University in Milton Keynes, I asked him to demonstrate Beagle2's scale. His answer was unbeatable, tapping into some uniquely British humour: he placed a replica of the barbecue-sized spacecraft in a supermarket trolley and wheeled it through the car park. A shot both hilarious and iconic was born.

Then, at the key moment, on Christmas morning in 2003, stars and celebrities joined our media throng for an agonising wait. This was not exactly mission control in Houston but a modest meeting room at the Open University's centre in north London.

Live on television, his shirt festooned with clip-on microphones, Pillinger was resolute as the clock approached the moment when the first message should have confirmed a safe landing. And he remained resolute when that moment passed.

Early days, he kept saying, no problem, a bold display of a stiff upper lip. But I caught sight of Judith's face which told a more forlorn story.

Nothing was ever heard from the tiny craft and there was no trace of it until now. The assumption was that it was lying in shattered pieces in the Martian dust.

And so the name Beagle entered the lexicon as a heart-warming example of plucky failure.

When a British mission to search for life beneath the ice of Antarctica was being planned, the chief scientist Martin Siegert told me he hoped it would not turn out to be "another Beagle".

The pristine waters of the ancient Lake Ellsworth, cut off for thousands of years, were the target of the drilling project. The quest was to see if life could survive in the icy darkness.

Lake Ellsworth scientists are hoping to win funding again

The Russians had already extracted water from another lake under the ice but the samples may have been contaminated. And an American project was drilling into a less isolated spot. The scientific prize - as with Beagle - was there to be seized by British hands.

But the team's hot-water drill could not be aimed as accurately as needed. Supplies of fuel to melt the ice were running low. And over Christmas 2012 - exactly nine years after Beagle - another British team faced crushing disappointment.

Of course, the ultimate example of near-triumph came from Captain Scott and his team in the Antarctic wilderness a century before that.

They made it to the South Pole only to find that the Norwegians had got there first. They then hauled back priceless geological samples but never made it, their bodies later found frozen in their tent.

Even so, Scott became established as a legend and inspired future generations of explorers. A key thread in the narrative of British exploration is a determination not to give up, a legacy of salvaging something positive from defeat.

So, the Lake Ellsworth scientists are hoping to win funding to try again. And British space scientists will have another go at Mars with a European mission in 2018.

Colin Pillinger himself never had the chance for a second attempt. But he always avoided using the word failure.

And, if he were alive today, he would surely argue that news of Beagle2 touching down intact proves him right, that Britain did manage to land on Mars, and by any standards that counts as success.