Google's Vint Cerf warns of 'digital Dark Age'

- Published

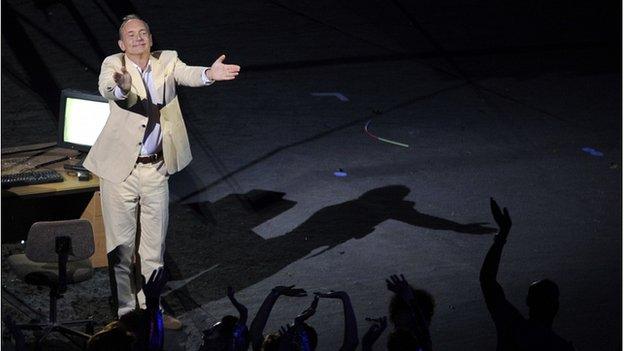

Watch Pallab Ghosh's full interview with Vint Cerf, internet pioneer, on his "digital Dark Age" warning

Vint Cerf, a "father of the internet", says he is worried that all the images and documents we have been saving on computers will eventually be lost.

Currently a Google vice-president, he believes this could occur as hardware and software become obsolete.

He fears that future generations will have little or no record of the 21st Century as we enter what he describes as a "digital Dark Age".

Mr Cerf made his comments at a large science conference in San Jose.

He arrived at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, external stylishly dressed in a three-piece suit. This iconic figure, who helped define how data packets move around the net, is possibly the only Google employee who wears a tie.

I felt obliged to thank him for the internet, and he bowed graciously. "One is glad to be of service," he said humbly.

His focus now is to resolve a new problem that threatens to eradicate our history.

Our life, our memories, our most cherished family photographs increasingly exist as bits of information - on our hard drives or in "the cloud". But as technology moves on, they risk being lost in the wake of an accelerating digital revolution.

What is the digital Dark Age? The BBC's Pallab Ghosh reports

"I worry a great deal about that," Mr Cerf told me. "You and I are experiencing things like this. Old formats of documents that we've created or presentations may not be readable by the latest version of the software because backwards compatibility is not always guaranteed.

"And so what can happen over time is that even if we accumulate vast archives of digital content, we may not actually know what it is."

'Digital vellum'

Vint Cerf is promoting an idea to preserve every piece of software and hardware so that it never becomes obsolete - just like what happens in a museum - but in digital form, in servers in the cloud.

If his idea works, the memories we hold so dear could be accessible for generations to come.

"The solution is to take an X-ray snapshot of the content and the application and the operating system together, with a description of the machine that it runs on, and preserve that for long periods of time. And that digital snapshot will recreate the past in the future."

A company would have to provide the service, and I suggested to Mr Cerf that few companies have lasted for hundreds of years. So how could we guarantee that both our personal memories and all human history would be safeguarded in the long run?

Even Google might not be around in the next millennium, I said.

"Plainly not," Vint Cerf laughed. "But I think it is amusing to imagine that it is the year 3000 and you've done a Google search. The X-ray snapshot we are trying to capture should be transportable from one place to another. So, I should be able to move it from the Google cloud to some other cloud, or move it into a machine I have.

"The key here is when you move those bits from one place to another, that you still know how to unpack them to correctly interpret the different parts. That is all achievable if we standardise the descriptions.

"And that's the key issue here - how do I ensure in the distant future that the standards are still known, and I can still interpret this carefully constructed X-ray snapshot?"

The concept of what Mr Cerf refers to as "digital vellum, external" has been demonstrated by Mahadev Satyanarayanan at Carnegie Mellon University.

"It's not without its rough edges but the major concept has been shown to work," Mr Cerf said.

- Published18 March 2013

- Published11 November 2010